Even in the US, South Asians say caste has proved hard to escape

Sam Cornelius knew that something was amiss when his job performance review unexpectedly took a huge hit one year.

It was 2013, and Cornelius had been working as a software engineer in the US for an Indian-headquartered information technology company for five years. Up until then, he said he had been given no indication that his work was lacking in any way.

He could think of nothing that would have prompted his performance rating to drop two levels from the previous year — except for an incident a month earlier at a dinner with his Indian manager and an American client.

During that dinner, the client, who was White, brought up the subject of caste discrimination in India, Cornelius said. He wanted to get the perspective of Cornelius and his manager, who were both born and raised in India.

India’s caste system is a fixed system of social hierarchy that historically defined a person’s societal rank and occupation based on the family they were born into. It dates back thousands of years, with its roots in Hindu scriptures, and has since spread to other South Asian religious communities. Similar systems are also found in some other parts of the world, particularly West Africa.

At the top of the Indian caste hierarchy are Brahmins, who were traditionally priests or scholars. Next are Kshatriyas, who were warriors and rulers. After that are the Vaishyas, who were merchants and traders. And following them are the Shudras, who were artisans and laborers. Thousands of sub-castes within those four categories further divide society.

And then there are the Dalits, formerly known as the “untouchables,” considered so low that they fall outside the caste system.

India’s constitution outlaws caste discrimination and established affirmative action programs for people from marginalized backgrounds, resulting in significant weakening of once iron-clad divisions, especially in cities. But people from oppressed castes still routinely report violence, discrimination and segregation.

Meanwhile, cultural norms surrounding caste are upheld through social constructs, such as who people socialize with and who they view as acceptable marriage partners.

Cornelius (who requested that his real name not be published for fear of social and professional repercussions) said his manager, a Brahmin, painted a “rosy picture” of the social hierarchy during that dinner. In the old days, he recalled his manager as saying, the caste system had been good for Indian society, prescribing a role and function for every person in the country.

Cornelius, a Dalit, said he pushed back at his manager’s comments, saying that for people from oppressed castes, the system was “a curse for the country.”

He says the subject of caste had never come up at work before and that he believes that conversation gave away his caste identity. About a month after he received his poor performance review, he says his manager transferred him to a project in India, uprooting his life and that of his family until he found a new job and moved back to the US.

Cornelius says he can’t definitively prove that his manager took those actions because of his caste identity. But he also believes there’s no other explanation.

“Other than that, I couldn’t see anything,” he said. “Because the same person used to praise me.”

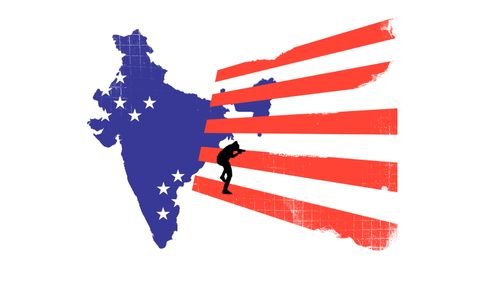

Caste has followed South Asians across oceans

Cornelius said caste bias isn’t something he expected to face when he came to the US, least of all in professional settings.

But the stigma of caste has proved hard to escape.

“Caste has been here (in the US) for a long time,” said Thenmozhi Soundararajan, executive director of South Asian advocacy organization Equality Labs. “Wherever South Asians go, they bring caste.”

Those CNN spoke to said that when they encountered caste bias in the US, it was typically among Indians who had recently moved to the country for work or higher education. They recounted overt and covert references to caste in casual workplace conversations, in roommate listings and at cultural events.

Caste’s notions also can trickle down through generations, including in marriage decisions that involve the input of families (as in Netflix’s “Indian Matchmaking”).

A survey published in 2018 by Equality Labs examined the ways that caste plays out in the South Asian diaspora. About 67% of Dalit respondents and 12% of Shudra respondents reported being treated unfairly at their American workplace because of caste. Those from marginalized castes also reported facing caste discrimination in American educational institutions and said they lived in fear of their caste being “outed.”

More than 1,500 people responded to the survey, which was distributed through direct contacts, community networks and social media and relied on self-reporting. The survey, while not scientific, offers evidence that cultural attitudes around caste have permeated American institutions, Soundararajan said.

“It shows us how pernicious it is, that it’s not just about interpersonal reactions, that this is a systemic and structural problem,” she said. “And so we need structural remedies.”

There are more than five million South Asians living in the US, making them among the fastest growing immigrant groups in the country. Though they comprise a small portion of the overall US population, Indian migrants account for large numbers of international students and high-skilled workers in fields including science, engineering and technology.

Despite reported instances of caste bias, discrimination and social exclusion in US workplaces and schools, the concept of caste is not well understood outside of the South Asian diaspora — though the system has obvious parallels to the way race functions in many nations, including in the US.

Much like racism in the US, the Indian caste system is deeply rooted and systemic in nature, persisting through cultural notions and institutions even after legal discrimination was abolished.

Though conditions have improved over time and have allowed both Black Americans and Dalit Indians to achieve some upward mobility, both groups are still more likely to experience poverty. And just as Black people face barriers because of their skin tone, Dalits and other marginalized castes face barriers because of the family they were born into.

It’s not always clear what caste a person is from just by looking at them. Lighter-toned skin can sometimes be an indication of dominant caste origin, but a primary indicator is often last names, leading some people from oppressed castes to change them. A person might also try to discern another’s caste by asking about their hometown, their religion (some caste-oppressed people have converted out of Hinduism) or whether they eat meat (many people from dominant castes tend to be vegetarian, while many people from marginalized castes are not).

Caste, unlike race, sex and religion, is not a protected category under federal or state laws in the US, and few institutions include it in their non-discrimination policies. That means when a person does face bias or discrimination because of their caste, there’s usually little they can do about it.

“There’s a real disincentive for caste-oppressed Dalit people to share their discrimination,” Soundararajan said, adding that many human resources departments and diversity offices don’t understand the dynamics of caste enough to appropriately address such problems.

Some see little reason to report bias

That’s been the experience of Maya Kamble, who also asked not to be identified by her real name because of the professional and social implications.

She recalled an incident that happened in 2012 under an Indian manager while she was working at a small technology firm in Washington, D.C.

Kamble, a Dalit, said her manager knew of her caste identity and was generally dismissive of her suggestions during meetings, something she says became a source of increasing frustration.

On one occasion, Kamble volunteered to help her manager out with a new tool at work. She said he told her not to touch it because she was “ill-fated,” using the Hindi word “manhoos,” which refers to a person who brings bad luck to others.

“He said that as a joke, but it was a direct reference to me coming from an ‘untouchable’ background, where people are considered pollutants or ill-fated or unlucky,” she said.

Kamble said she saw no point in taking the incident to her employer’s human resources department. She also feared that reporting it could potentially backfire and jeopardize her temporary visa status.

“We cannot complain to HR because HR is generally American,” she said. “They don’t understand the context of caste.”

Instead, she decided to confront her manager directly, who she said apologized for the incident. Still, she felt the comment and her manager’s other actions had created a hostile environment for her, and she began looking for another job — one where she wouldn’t have a South Asian manager.

“It doesn’t matter what position you are, how qualified you are, how best you are at your job,” she said. “The people from dominant castes, they always have this perception, and they want to impose it on us.”

But one discrimination case could set a precedent

But the tide may be about to turn when it comes to how the US deals with caste discrimination.

On June 30, California authorities sued Cisco, the technology company, and two of its employees for allegedly discriminating against an Indian engineer because he was from a lower caste.

It is the first time in US history that caste is at the center of a discrimination case, according to Soundararajan.

The lawsuit, filed by California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing, alleges that Cisco “engaged in unlawful employment practices on the basis of religion, ancestry, national origin/ethnicity and race/color” against the Dalit engineer, who was not named in the complaint.

The lawsuit alleges that the engineer received “less pay, fewer opportunities, and other inferior terms and conditions of employment” because of his identity. When he challenged those conditions, his managers retaliated against him, the complaint states.

California authorities also accused Cisco of failing to take steps to prevent caste discrimination after multiple investigations, despite having employed a predominantly Indian workforce for decades.

Cisco has said that it would “vigorously defend itself” against the allegations, adding that it had followed processes to investigate the employee’s concerns.

The case is still pending. But if the court rules against Cisco, it could have ramifications for all American companies with Indian employees, Soundararajan said.

“Whether it’s the assembly line or the C-suite, it’s really important that we start to examine this problem because American institutions are failing to protect caste-oppressed people,” she said.

Slowly, progress is being made

At least one US institution has already taken steps to protect against caste discrimination.

In December 2019, Brandeis University in Massachusetts added caste to its non-discrimination policy along with race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation and other categories.

The move came after Laurence Simon, a professor of international development who has studied social exclusion, said some Dalit students confided in him that they felt shunned by other Indian students they encountered on campus.

“It appeared to me, at least anecdotally, that there was within the South Asian community an ongoing discrimination based on the attitudes that many people grow up with in the old countries,” Simon said.

The university then formed a committee made up of faculty, staff and students to explore how issues of caste played out on campus and how it might address them.

The committee gathered information about people’s experiences around caste, which mostly involved social exclusion rather than overt discrimination, said Mark Brimhall-Vargas, chief diversity officer and vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion at Brandeis. But Brandeis ultimately decided to include caste as a protected category in its discrimination policy anyway.

“Our thought was, ‘Well, why wait for it to get that bad?'” Brimhall-Vargas said. “We wanted to address it before we ever got to something that was extremely serious around discrimination or harassment.”

Brimhall-Vargas said he knows of no other American university that expressly prohibits discrimination based on caste. But since Brandeis updated its policy, he says other colleges and universities have contacted him as they consider similar moves.

Equality Labs is advocating for US institutions, states and municipalities to make caste a protected category. Once that starts happening, activists can begin collecting data and developing solutions, such as caste competency trainings in workplaces and universities, Soundararajan said.

Ultimately, the hope is that caste becomes a protected category at the federal level. And that more Americans — not just those born in India — will commit to delivering on the promise of liberty and justice for all.