Día de Muertos festivities spread across the border as a homage to the departed and respect for Mexican culture

A community altar constructed by textile artist Genevieve Guadalupe stands in the art gallery of the nonprofit Tohono Chul botanical gardens in Tucson, Arizona, on Oct. 11, 2025. The altar holds cards where visitors write the names of departed loved ones and leave messages. Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

A Tucson couple keeps borderlands memories alive with Muertos altars.

Editor’s note: This story was co-published with Puente News Collaborative in partnership with palabra. Puente News Collaborative is a bilingual nonprofit newsroom, convener and funder dedicated to high-quality, fact-based news and information from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Words by Anita Snow, @asnowreports

Edited by Dianne Solis, @disolis

TUCSON, Ariz. – Antonio Estrada and Gloria Valenzuela’s remembrances of growing up in the borderlands are woven into every Día de Muertos altar they have constructed over more than three decades.

A bottle of Seagram’s 7 always stands on the altar alongside the photo of Estrada’s father because he loved his whiskey. His mother’s favorite color was pink, so the framed image of the seamstress and mother of six from South Tucson is always flanked by pink blossoms.

Valenzuela’s memories of her hometown of Guadalupe, Arizona, just outside Phoenix, shape homages to her family.

“It’s a way to communicate with our loved ones in a very personal way, and to respect their memory,” said Valenzuela, who learned altar-making from her late mother, a Mexican American with roots in the central state of Jalisco. Estrada, who, like many Mexican Americans, grew up without the tradition, learned from Valenzuela, his wife.

Artist Antonio Estrada in front of cajitas, or mini-altars, at a workshop he and his wife, Gloria Valenzuela, held on Sept. 27, 2025, at the Tohono Chul botanical gardens in Tucson. Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

The couple is passionate about teaching altar-making to those just discovering the practice amid a vibrant surge of Day of the Dead celebrations across the southwestern border regions and into U.S. cities farther north. The tradition accelerated with the 2017 release of the animated film “Coco,” acclaimed for its meditation on life, death, family, and Mexican culture.

With Indigenous roots that predate the Spanish Conquest, Mexico's Day of the Dead overlaps with the Christian observance of All Saints Day and All Souls Day on Nov. 1-2. There are key distinctions, and indigenous traditions honoring the dead existed before the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s.

U.S. CELEBRATIONS

Cities with large Mexican-American communities, of course, such as Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Austin, and San Antonio, have celebrated the holiday for decades.

Public celebrations will roll out across the U.S. border states again this year, with a huge All Souls Procession that has been held in Tucson annually since 1990. The El Paso Mexican American Cultural Center, which opened earlier this year, expects more than 50,000 people at this year’s festival and parade. The Texas towns of Marfa, Presidio, and McAllen will also roll out festivities, too.

For 35 years in Tucson, Estrada and Valenzuela have shared the tradition with family, friends, and the public through their large-scale and small-scale altars. Their largest was a public installation 16 feet by 10 feet that they built in 2019 at the nonprofit Tohono Chul botanical gardens, situated on the traditional lands of greater Tucson’s Indigenous peoples.

The couple was back at Tohono Chul in late September to teach a workshop about mini altars built wholly inside a shoebox-sized cajita, or small box, of cardboard, balsa wood, clay, or any other material to create a more intense look at a single ancestor or a small group. The cajitas Estrada and Valenzuela displayed included a yellow shadowbox remembering the five cats they have shared over more than 40 years of marriage.

Workshop participants display their cajitas, or shoebox-sized mini altars, led by artists Antonio Estrada and Gloria Valenzuela at the Tohono Chul botanical gardens in late September 2025. The artists' own example, a yellow shadowbox, memorializes the five cats they have shared during their more than 40-year marriage. Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

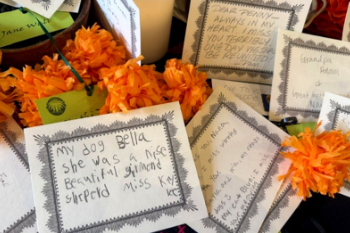

An art gallery elsewhere on Tohono Chul grounds features a Dead of the Dead art exhibit anchored by a soaring community altar designed by Genevieve Guadalupe, a local Mexican-American printmaker and fiber artist. The installation includes cards to write the name of a departed loved one, and maybe even add a message.

A child left a card for Bella, “a nise beautiful girmend sheperd.” Another card told Grandma Theresa she was missed daily. “I love you Grammy,” it added. “Go Cubs.”

Guadalupe, who is originally from Puebla, Mexico, said such community altars allow people to share memories of loved ones, and remind everyone that the day is about honoring the dead.

“It’s something very serious and very special,” Guadalupe said. “I have mixed feelings about the way some people conflate it with Halloween. But to me it’s also not a religious holiday. It is a celebration to remember those who were dear to us who have passed, to have them close to us again.”

A card on the community altar at the Tohono Chul botanical gardens bears a child's message to a beloved pet dog named Bella, "a nise beautiful girmend sheperd." Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

Estrada and Valenzuela also insisted that while the holiday is joyous, celebrations should be dignified.

“As long as people understand the tradition and are respectful of it, we’re good with it,” he said.

Altars can inspire powerful emotions. “I have seen people stand in front of our altars just start sobbing,” Estrada said.

CONSTRUCTING AN ALTAR

In Mexico, altars traditionally are built in homes or atop tombs at the local cemetery, where families gather to eat, drink, and accompany their ancestors. Favorite foods, beverages, photos, and other mementos are placed as ofrendas, or offerings.

Common items include calaveritas, or little sugar skulls, and pan de muerto, or bread of the dead, with crossed bones and sugar sprinkles. A typical altar also features orange Mexican marigolds called cempasúchil, which are said to attract the souls of the dead with their bright petals and perfume.

Traditional pan de muerto, or bread of the dead, is shown alongside mini altars constructed at a workshop led by artists Antonio Estrada and Gloria Valenzuela. The sweet bread is eaten on and around the Day of the Dead in Mexico and placed on altars to remember departed loved ones. Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

Styles of altars vary from place to place, and opinions on what to add can differ. But Estrada and Valenzuela said several additional elements should be included to ensure an altar is complete:

EARTH: Things that grow and come from nature, like flowers, plants, fruit, corn, and especially food that departed loved ones enjoyed.

WIND: Things that move when passed by or touched, such as leaves from a tree or papel picado, the colorful cut pieces of paper strung together and hung during Mexican celebrations.

FIRE: Candles, incense, or the burning of sage to represent prayers elevated to heaven. The smoke and aroma guide the departed back to commune with loved ones, according to lore.

WATER: A glass of water is necessary for thirsty spirits after a long journey, according to the couple. Coffee, chocolate, beer, and tequila are also welcome.

ONE LAST THING: Valenzuela said they like to include a candle on their altars to welcome a lonely soul who wasn’t remembered by their family.

“We want to make sure they know they haven’t been forgotten,” she said.

Cajitas, or mini altars, constructed by artists Antonio Estrada and Gloria Valenzuela, are shown at a workshop on Sept. 27, 2025. Photo by Anita Snow/Puente News Collaborative

—

Anita Snow is a freelance writer focusing on immigration and the border from Tucson, Arizona. She previously worked for The Associated Press as a Latin America correspondent and as a reporter covering the U.S. Southwest. @asnowreports

Dianne Solis is a freelance journalist. She has worked as a staff writer for The Dallas Morning News and The Wall Street Journal in Texas and Mexico. Her work has been featured on KERA public radio, The Texas Observer, The Guardian, and El País. @disolis