She allegedly told her boyfriend to kill himself and he did. Did she commit a crime?

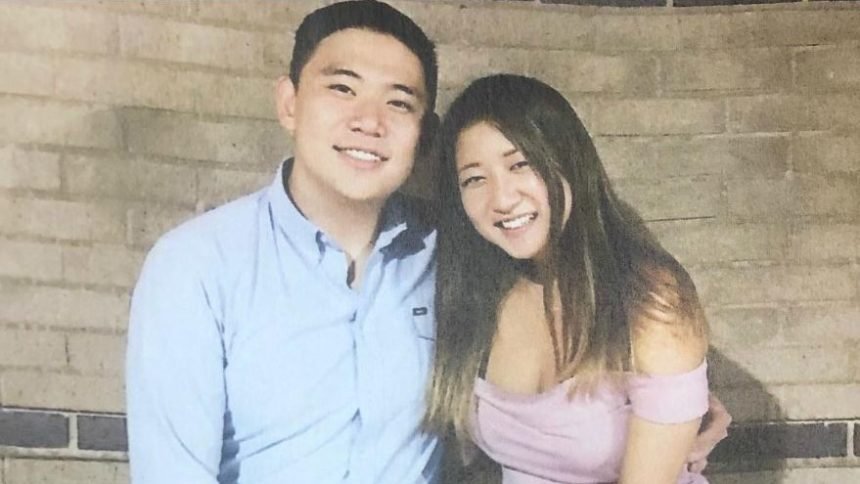

Instead of graduating from Boston College on May 20, and sharing a glorious day with his family and friends, 22-year-old Alexander Urtula took his own life. He did so just hours before his graduation ceremony by leaping off a parking garage. His girlfriend of 18 months, Inyoung You, now stands charged with his homicide. Why? Because allegedly she relentlessly encouraged him to kill himself.

As such, a Boston grand jury returned an indictment of involuntary manslaughter against her. If convicted, she could be sentenced to up to 20 years in prison. She is currently in South Korea, having withdrawn from Boston College this past August. But prosecutors are “cautiously optimistic” that she will come back to the US to face the charge against her.

Central to the prosecution’s case is that Urtula was suicidal and depressed, and therefore in a vulnerable state. Additionally, prosecutors note that You tracked his location to the garage, was present when he jumped, and was “physically, verbally and psychologically abusive,” according to authorities. In fact, investigators say they found more than 47,000 text messages in the 2 months preceding his death that contained a barrage of ugliness, including a message to Urtula that the world would be better without him in it. In general, the texts, as summarized by authorities, can be characterized as hateful, demeaning, rude, and utterly offensive.

Unquestionably, You’s texts and overall treatment of Urtula, as laid out by authorities, were indecent and inhumane. There is little dispute about that. Her alleged actions should be condemned in the starkest of terms. And the humanity in all of us would want some form of justice served.

But are You’s actions criminal? The answer to that question is not legally obvious.

CNN has not been able to reach You or her counsel for comment.

Presuming authorities are successful in bringing her back from South Korea, it would be hard to imagine that a 12-member jury from Boston, or any other community, would be sympathetic.

But the prosecution of You will not ultimately be decided by feelings or emotions. Her criminal culpability must be determined by applying well-established principles of law.

As an initial matter, in order for You to be found guilty of involuntary manslaughter, her actions in relation to Urtula’s death must be found to be wanton and reckless. Many might assume that without a doubt her actions were both of those things. But pause for a moment and consider what she is alleged to have done and how that squares with the core principles of our democracy.

Doesn’t everyone have the right to speak their mind freely and plainly — no matter how unpopular, distasteful, or disgraceful, the message? That is a core principle of the Constitution. Here, there is no indication that the texts exchanged between You and Urtula were not voluntary exchanges between two parties in a consensual relationship. Therefore, harassment laws do not apply and cannot be implicated.

Further, the law says that no person has a legal duty to render aid to another — unless they are the very cause of why another person is in peril.

These issues were raised in a similar case involving another young woman, Michelle Carter, who encouraged her boyfriend, Conrad Roy, to take his own life. She was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter two years ago. After much legal debate, her conviction was upheld and she is serving a 15-month jail sentence. The US Supreme Court has yet to declare whether it will take up the case.

Carter wasn’t present when Roy committed suicide, in contrast to You, who authorities say was there when Urtula jumped from the parking garage. This critical fact might lead a casual observer to conclude that You’s case would, therefore, be even more egregious, making her prosecution more viable. But we must remember that being present doesn’t require a bystander to provide aid to someone in need. The principal legal question in You’s case will be whether she was the cause of Urtula’s peril and therefore legally responsible to provide aid.

In Carter’s case, she was a central planner and co-conspirator in Roy’s death. She knew of his plan to kill himself and assisted him virtually in it — going so far as to encourage him to get back in his carbon monoxide-filled truck after he had a change of heart about his suicide. Further, she was on the phone with Roy as he was carrying out his plan. This, the court noted, made her “virtually present.”

After Roy had gotten back into his truck full of noxious gas, Carter had one last chance to save him. She could have called 911, yet she failed to do so. The court concluded that her failure to act, and her having participated in Roy’s perilous reentry into his truck, was enough to constitute creating his peril. It was on this basis that the judge, in her bench trial, found her guilty.

In You’s case, all that prosecutors have made public is that she sent Urtula an enormous number of denigrating and demoralizing text messages while allegedly knowing of his mentally fragile condition. Additionally, they are highlighting the fact that she was present when he leaped to his death. In doing so, they are likely preparing to make the argument that her lack of humanity overpowered Urtula’s free will. Again, this is a powerful moral argument, but whether it is legally sustainable is another matter.

The critical inquiry is this: Can words alone, in the absence of other conduct, carry the day? So far, in the You matter, words are all we have.

And no matter how awful, nasty and mean spirited those words are, they may well not be enough for an appellate court to uphold a potential conviction after trial.

In the final analysis, prosecutors will have to show much more than You’s inhumanity if they have any hope of sustaining their case against her.