‘I think he gets it now’: New York Mayor Bill de Blasio searches for his footing in coronavirus crisis

New York City announced its first confirmed case of Covid-19, the infection caused by coronavirus, on March 1. That same day, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio and his health commissioner put out statements reassuring the city that its political and public health leadership was “prepared” for what came next.

They were not.

One month later, New York is the epicenter of the world’s coronavirus crisis. By Wednesday morning, more than 75,000 people had been infected statewide. Nearly 1,600 have died. Hospitals and health care workers are being stretched to their breaking points. New York City’s streets alternate between an unnerving silence and the cutting blare of emergency vehicles.

The catastrophic spread of the virus, which has claimed young and old, the anonymous poor and civic heroes, has also put a national microscope on de Blasio, a two-term mayor whose estimable progressive record is often overshadowed by a long-running rivalry with Gov. Andrew Cuomo and a difficult relationship with the local press corps.

While Cuomo has become a political star outside New York for the first time in his long career after his coronavirus press conferences — which mix detailed statistics with a projection of personal empathy absent from White House’s daily briefings — became a television sensation, de Blasio’s public-facing performance has been faced with a rougher appraisal.

New York Magazine, last Thursday, published a scathing tick-tock of the mayor’s halting response to the crisis. Its verdict: “When New York Needed Him Most, Bill de Blasio Had His Worst Week As Mayor.” Two days later, Politico’s New York bureau ran a similarly biting account, which painted the mayor as serially indecisive or, worse, unduly skeptical of expert warnings.

“It’s easy to sit on the sidelines and have an opinion,” de Blasio press secretary Freddi Goldstein said in a statement. “The mayor carries the responsibility of 8.6 million New Yorkers. He must think about their safety, their livelihood, their education. Every decision he has made has been deliberate and thoughtful. That’s what you need in a crisis.”

Former top de Blasio aides interviewed for this story both acknowledged the mayor’s errors and bristled at what they described as a media narrative that ignored Cuomo’s own initial hesitance to act. Both leaders wrestled with questions over shelter-in-place orders and the decision, after days of uncertainty, to close city schools. On most major policy issues, they argued, de Blasio and Cuomo have pulled — eventually — in the same direction.

Mixed messages

But de Blasio, in his defiant style, dug himself a deeper hole. His early declarations, before the first cases turned up, urging New Yorkers to go about their business, were followed by a bizarre stretch capped off by a visit to his gym on March 16, the first day of school closures — as the city settled in anxiously for a coming storm.

Only two days earlier, de Blasio had pushed back against increasingly desperate calls to shut down high-density gathering locations.

“I am not ready today at this hour to say, let’s have a city with no bars, no restaurants, no rec centers, no libraries,” he said on March 14. “I’m not there.”

Many New Yorkers agreed with him. On that mild Saturday night, they flocked to crowded bars and restaurants.

Others watched them, from afar on social media, with horror. By Sunday night, de Blasio reversed course and announced that many of the same locations that hosted revelers the night before would be closed or limited to take-out service in the coming days. The following Tuesday, de Blasio went a step further, saying New Yorkers should be prepared for a “shelter-in-place” order. Cuomo quickly rejected the prospect — before initiating a similar policy just a few days later. Still, the mayor’s early moves to downplay the threat undermined his credibility with an increasingly jittery public.

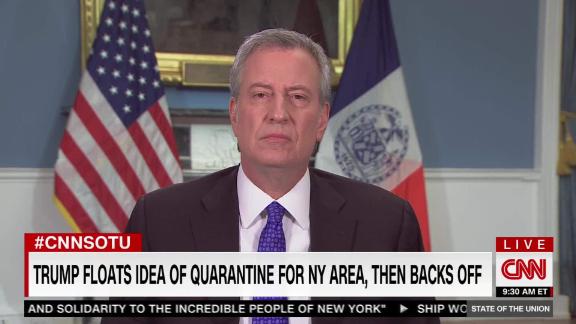

During an appearance this past Sunday on CNN’s “State of the Union,” de Blasio was confronted with some of his earlier appeals for calm and normalcy, and asked by host Jake Tapper if his message was, in part, to blame for the virus’s rapid spread in New York.

De Blasio, who had been critical of the White House’s response, demurred when asked if he should face the same scrutiny.

“We should not be focusing, in my view, on anything looking back on any level of government right now. This is just about how we save lives going forward,” the mayor said. “We all were working, everybody was working with the information we had, and trying, of course, to avoid panic, and at that point, for all of us, trying to keep — not only protect lives, but keep the economy and the livelihoods together, keep ensuring that people had money to pay for food and medicine. I mean, this was a very different world just a short time ago.”

His invocations of “a very different world” have roiled some New Yorkers, who point to the very similar scenarios that played out in China and Italy before the crisis reached American shores — and its largest city. Cuomo conceded in his press conference on Tuesday that the state has been consistently on its heels.

“It was coming here,” he said. “We have been behind it from Day One since it got here. And we’ve been playing catch-up. You don’t win playing catch-up. We have to get ahead of it.”

A tonal shift

Amid the criticism, and the mounting death toll, de Blasio’s tone has changed.

Taking his own advice, he has mostly set aside any criticism of President Donald Trump. His own press briefings are, much like Cuomo’s, steeped in worst-case projections and increasingly sharp demands that New Yorkers adhere to stay-at-home and social distancing standards.

When the USNS Comfort arrived in New York Harbor on Monday morning, de Blasio offered a weighty welcome.

“There have been times in recent days when a lot of New Yorkers have felt alone. When a lot of New Yorkers have felt a sense of not being sure what’s coming next. Not being sure if help would come,” he said. “Well, I want to say to all New Yorkers, we have evidence here that you are not alone. We are not alone. Our nation is helping us in our hour of need.”

The mayor’s shift to a full embrace of stricter tactics designed to “flatten the curve” — and away from his personal inclinations, like closing schools only as a last resort — coincided with the New Yorkers’ own panicked turn.

“I think when the public health implications and projections started to firm up last week, on just how grave this was going to be, you saw a mayor become much more decisive and much less deliberative,” former de Blasio spokesman Eric Phillips said. “And that isn’t his natural posture. He is a deliberator. For better or for worse, he starts from a place of deliberation. And that often serves him well.”

Rebecca Katz, a former top adviser to de Blasio, traced the change to around the time of his gym visit two weeks ago, as the scale of the crisis — and dire forecasts of what was to come — became impossible to ignore. She attributed de Blasio’s sometimes tortured rhetoric in the run-up, including a riff in which he encouraged New Yorkers to visit their favorite locals bars on the night before they would be shuttered, to an instinct that has, under difference circumstances, served him well.

“He’s a New Yorker who cherishes New York things. And I think just like a million New Yorkers were grieving the loss of life as normal, he was, too. Except that as the leader, you have to be the one to give it up first. That’s where it got tricky,” Katz said. “I think he gets it now.”

New York moves fast and there have been, over the last few days, green shoots of optimism have opened up amid the misery. Officials say number of new cases, though mounting in number, is slowing its rate. Federal aid is making itself seen, as new hospitals, one floating and another growing inside the cavernous Javits Center come online and prepare to see patients.

But there are still questions to answer — the kind that might have tempted de Blasio into a gaffe a couple weeks ago. On Tuesday, a reporter asked de Blasio at a press conference at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Queens, where an emergency hospital is being stood up, about the prospects of the U.S. Open, the Grand Slam tournament that typically arrives in the borough late each summer.

“August may be a very much better time, or we might still be fighting some of these battles,” de Blasio said, staying on message. “We don’t know yet.”