Elephant seals enter ‘sleep spiral’ during deep ocean dives

During REM sleep

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

Northern elephant seals might be masters of multitasking in the animal kingdom because they’ve learned how to sleep and dive at the same time — all while avoiding predators.

The elephant seals can spend seven or eight months on foraging trips in the North Pacific Ocean and travel for thousands of miles away from land, which led researchers to question how and where the marine mammals sleep in the high seas.

A new study, involving seals fitted with caps similar to those worn by humans in sleep clinics, revealed that the seals sneak in short naps during deep dives while holding their breath.

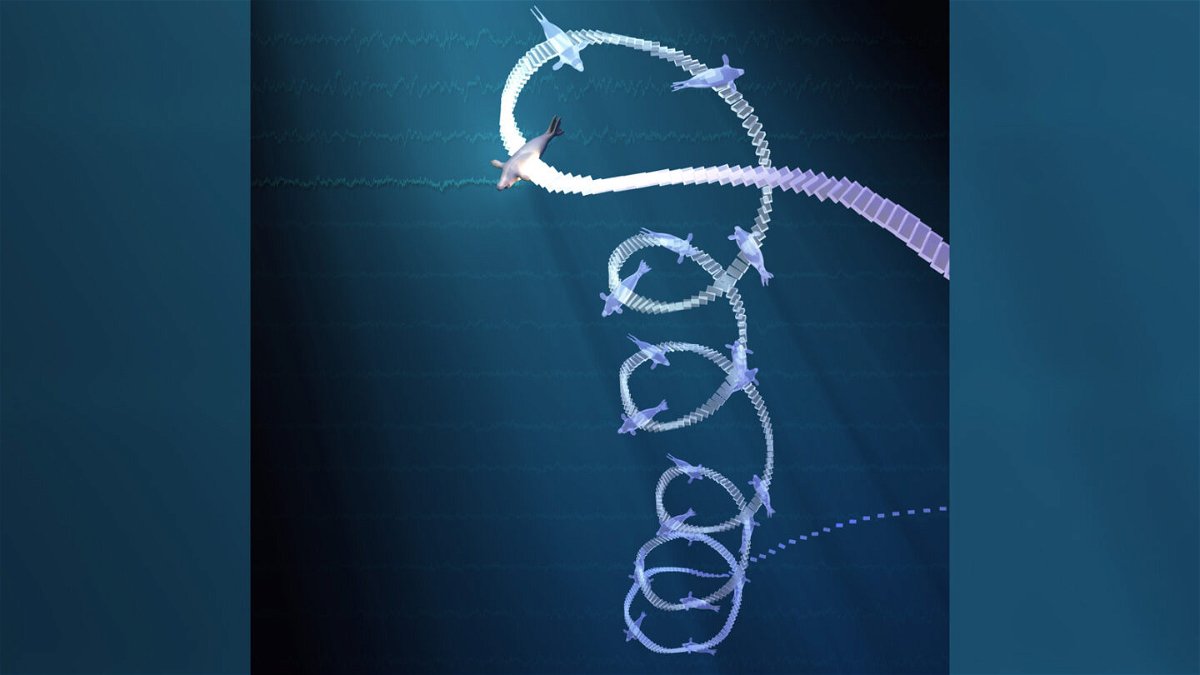

When the seals experience sleep paralysis as they enter rapid eye movement, or REM, sleep, they lose control of their posture and continue to spiral down in a corkscrew pattern. The researchers refer to this as a “sleep spiral.”

The research marked the first time scientists recorded brain activity in free-ranging wild marine mammals, capturing data from 104 sleep dives. A report detailing the findings was published Thursday in the journal Science.

“Imagine waking from a human snore-induced sleep at the bottom of a pool and then having to swim quickly to the surface before drowning,” said study coauthor Terrie Williams, director of the Integrative Carnivore EcoPhysiology Lab and comparative ecophysiologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Seals do this every day — truly an amazing master switch of a brain!”

The 10-minute naps during these 30-minute dives help elephant seals get about two hours of sleep per day during foraging trips, as opposed to the 10 hours they catch while snoozing on the beach during breeding season, the researchers said.

The African elephant currently holds the record for the mammal that gets the least amount of sleep, averaging two hours a day based on its movement patterns, but after this new study, the elephant may have a rival in the elephant seal.

And to reach these findings, researchers had to get creative to capture the brainwaves of wild seals.

Sleeping at sea

Some animals have unusual evolutionary adaptations to fit in sleep while avoiding predators and other risks, such as sleep-chewing cows, sleep-standing horses and frigate birds that can sleep and fly at the same time. But marine mammals that live in the open ocean face even more challenging conditions.

“As of right now, we don’t have any understanding of how and when marine mammals sleep at sea, and how our activities as humans might impact their ability to sleep,” said lead study author Jessica Kendall-Bar, postdoctoral fellow at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. “Studies have only ever looked at marine mammal sleep in captivity, but clearly that’s not an accurate representation of how they sleep in the wild.”

The researchers developed a system similar to an electroencephalogram, or EEG, but it was streamlined, waterproofed and able to withstand the pressures of deep ocean depths, Williams said.

“To monitor sleep, we created a flexible neoprene headcap with gold sensors that monitor the sleep signals generated by the brain,” Kendall-Bar said.

“We use the same sensors that are used in sleep clinics that help diagnose humans struggling with insomnia, narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and other sleep disorders. The logger that stores this sleep data also logs the animal’s three-dimensional position and behavior so that we can recreate what these sleeping dives look like.”

Kendall-Bar first tried her device on elephant seals temporarily housed at UC Santa Cruz’s Joseph M. Long Marine Laboratory when developing the EEG instrument. Then she attached them to 13 juvenile female elephant seals that are part of a colony at Año Nuevo State Park in Pescadero, California.

The sensor-wearing seals were also released on a beach at the southern end of Monterey Bay. As they swam back to Año Nuevo and crossed the deep Monterey Canyon, researchers gathered data on their diving behavior.

“I spent a lot of time watching sleeping seals,” Kendall-Bar said. “Our team monitored instrumented seals to make sure they were able to reintegrate with the colony and were behaving naturally.”

To analyze all the data captured by the recorders, Kendall-Bar developed an algorithm to identify the periods of sleep for each seal and transform them into 3D visualizations to see how the body positions of the mammals changed as they entered REM sleep.

“This visualization allowed us to see that the seal turned upside down as it transitioned to REM sleep,” she said. “This suggests to us that the seal lost control of its posture and became paralyzed at depth as it transitioned to REM sleep.”

Deep dives

To avoid predators such as killer whales and sharks, the elephant seals observed by the study team spent about one to two minutes at the ocean’s surface to breathe. Afterward, the animals would go on 30-minute deep dives, holding their breath the entire time.

Then, at safe depths, it was time for a nap. The brainwaves of the seals showed the mammals entered a deep sleep stage called slow-wave sleep — even as they continued a controlled downward glide during their dives.

Descending in a corkscrew spiral pattern, each slumbering seal looked “like a falling leaf,” study coauthor Williams said. In shallow waters, the elephant seals even reached the seafloor, where they would rest.

Previous research suggested the seals may be doing “drift dives,” stopping swimming and slowly sinking, said study coauthor Daniel Costa, distinguished professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and associate director of UC Santa Cruz’s Institute of Marine Sciences.

“Now we’re finally able to say they’re definitely sleeping during those dives,” Costa said, “and we also found that they’re not sleeping very much overall compared to other mammals.”

His lab has worked with elephant seals at Año Nuevo for more than 25 years, allowing the researchers to identify a “biochemical signature for sleep” that could be applied to Costa’s existing rich dataset about wild seals to determine the average amount of time they sleep while foraging.

There is no evidence to suggest that sleeping for such short periods negatively affect the seals, but it would be interesting to monitor the sleep rebound the animals experience when returning to land, the researchers said.

Understanding where marine mammals feed and breed has helped scientists and conservationists develop parameters for protected areas for those at risk of endangerment and extinction. But the animals’ preferred resting areas, or “sleepscapes,” also need to be considered.

Elephant seals sleep the most along the coast and near their foraging grounds, and that data could be used to see how shipping traffic could affect the seals. While the elephant seal is a species considered to be of least concern when it comes to conservation, others, such as the Hawaiian monk seal, are endangered. Understanding the sleep habitats of endangered seals could help conservationists protect those areas where they rest in the ocean.

“By looking at the sleeping patterns of seals at sea you can develop ‘nap maps’ — areas of critical habitats for resting that may be as important as hunting grounds that should be preserved for the animals,” Williams said. “Everyone needs a safe zone for sleeping to survive.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Sign up for CNN’s Sleep, But Better newsletter series. Our seven-part guide has helpful hints to achieve better sleep.