9 Black modernist architects and the landmarks they designed

Elon Schoenholz // Getty

When most people imagine modern architecture, names like Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Charles and Ray Eames come to mind; typically, it’s a white man (or, sometimes, the rare white woman). Their designs are now landmarks visited by thousands, but beyond this well-established canon lies a whole population of architects who continue to struggle for recognition in a field notorious for its lack of diversity.

While there has been progress over the years, new Black architects continue to face challenges entering the field. In 2022, only 3% of newly licensed architects were Black, compared to 70% who identified as white, 15% Asian, and 10% Hispanic and Latino, according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards’ 2023 report. The share of Black architects has only gone up 1 percentage point since 2018.

The industry has long excluded Black architects in systemic ways with laws and policies that denied them training and education in architecture, access to licensure exams, and membership in professional organizations.

Even when Black architects overcome these obstacles, they are still often overlooked.

“Historians are finding that many of them worked in larger architectural firms under white architects of record and oftentimes, their contributions were diminished or even ignored,” Joan Weinstein, the director of the Getty Foundation, told Stacker. Weinstein also pointed out that many of the buildings these architects worked on were in Black communities, which didn’t garner the same kind of attention that new structures built in upscale white neighborhoods might, for example.

Researchers haven’t fully quantified the continued effects of this exclusion, but it was never more evident than when the Getty Foundation realized in 2020 that none of the 77 grants it had awarded since 2014 to help preserve modernist buildings went to those designed by Black architects.

The institution partnered with the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund on a two-year $3.1 million grant program called Conserving Black Modernism to elevate modern architecture by Black architects and designers. After seven months of deliberations, the nine-member jury chose eight locations in 2023.

“It’s an opportunity for us to course-correct the way we understand architectural history and to center Black American architects,” Brent Leggs, executive director of the Action Fund, told Stacker. The Getty and the Action Fund expect to announce the next round of Conserving Black Modernism grants in July 2024.

In the meantime, Stacker is highlighting the nine Black modernist architects vetted by both institutions and eight examples of innovative architecture they designed. Just like the pioneering modernists of Europe post-World War I, these Black architects were looking for ways to build structures that could benefit the living conditions of communities using new materials and engineering techniques like reinforced concrete, open floor plans, and curtain walls.

Read on to learn about nine Black modernist architects that should be on your radar and the landmarks they built.

Nicole Bissey // Getty

Charles McAfee: Charles McAfee Swimming Pool and Pool House

Location: Wichita, Kansas

Charles McAfee, born in Los Angeles on Christmas Day in 1932, became one of the first African Americans to graduate with an architecture degree from the University of Nebraska in 1958. McAfee believed in modernism’s community-focused ethos, and his projects reflect this spirit: from a manufacturing plant that would provide 50 full-time jobs to the Wichita swimming pool that bears his name.

The pool, built in a historically Black neighborhood, was one of the first to offer Black swimmers in Kansas access to competition-length swimming lanes. It featured double sand-blasted concrete shade structures that provided shelter from the heat and concrete light towers for those looking to swim at night. Its modular concrete and brick pool house also offered a minimalist environment for showering and changing clothes.

McAfee would go on to win awards from the American Institute of Architects in Kansas and the Federal Housing Administration. He also served as the president of the National Organization of Minority Architects.

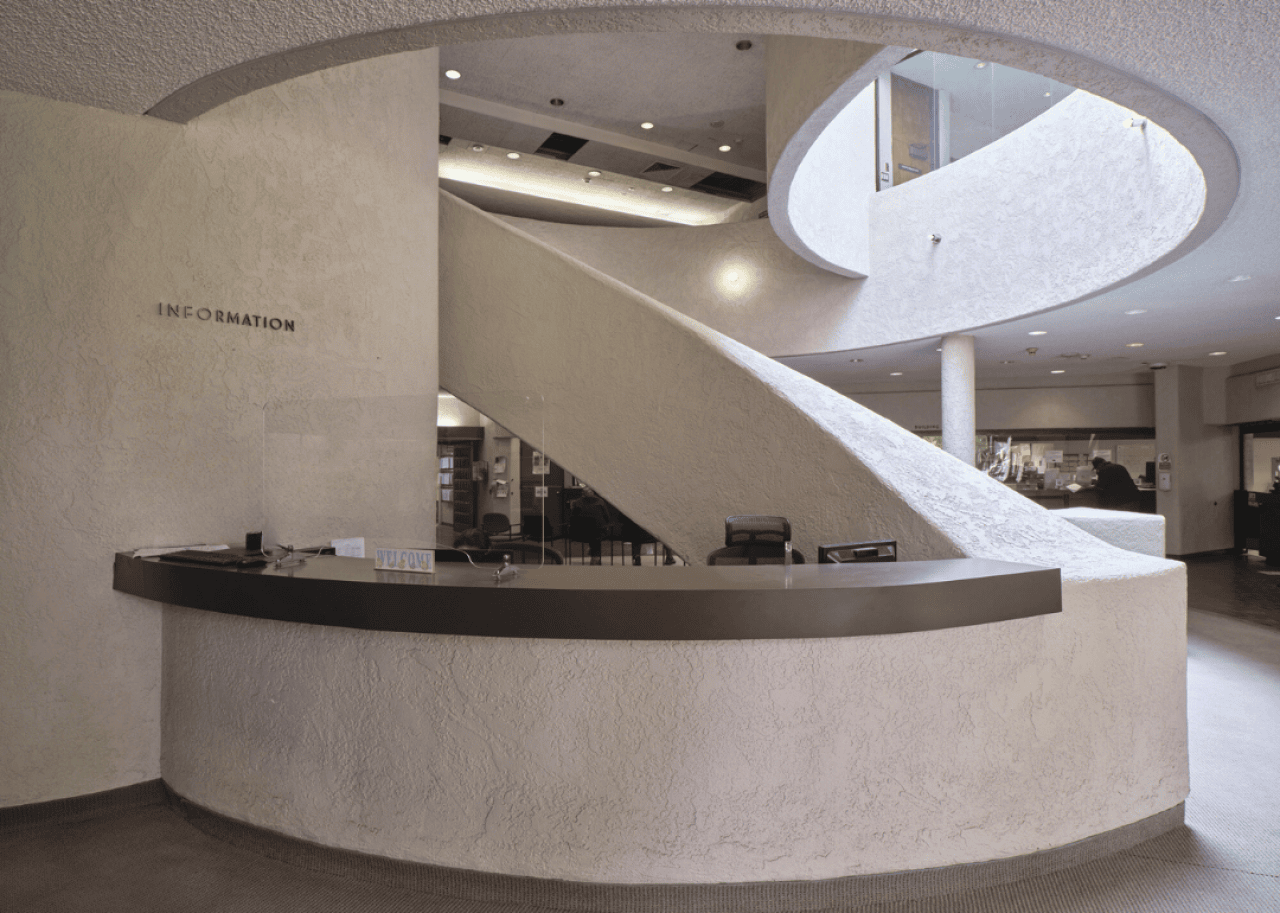

Elon Schoenholz // Getty

Robert Kennard: Carson City Hall Building

Location: Carson, California

After receiving his architecture degree from the University of Southern California under the G.I. Bill, Robert Kennard found systemic barriers blocking his path to work in the field. The sheer amount of rejection he received—with some architecture firms telling him, “We don’t hire colored people”—prompted Kennard to help open doors for others who faced similar exclusion.

After establishing his firm, Kennard Design Group, in 1957, he recruited and mentored Black students in Los Angeles. He also formed the Minority Architecture and Planning Organization, which later became the National Organization of Minority Architects. Kennard left his mark on civic architecture, designing metro stops in Washington D.C., parking garages at the Los Angeles International Airport, and the Carson City Hall Building.

The Carson City Hall project came about as Carson became an independent city in 1968. Carson officials selected three architects to work on the project, and their choices reflected the city’s diversity. The architects included American Robert Alexander, Japanese American Frank Sata, who the U.S. detained in Japanese relocation camps during World War II, and Kennard, who would be the executive architect.

Nautically inspired, the building has a three-wing design that forms a Y. The sides of the structure echo ship windows with outriggers and city council offices set atop the ship’s bridge. Its interior also features a graceful staircase that ascends to a nautilus-shaped atrium.

Elon Schoenholz // Getty

Robert Kennard and Arthur Silvers: Watts Happening Cultural Center

Location: Los Angeles, California

Arthur Silvers was an architect whose work went beyond design, fighting for justice in housing and employment. As chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality in Los Angeles in the 1960s, Silvers organized protests against businesses with unequal practices and took legal action against landlords who refused to rent to Black tenants.

Kennard and Silvers often worked together on projects like the building that’s now Thurgood Marshall College at the University of California, San Diego; Temple Akiba in Culver City, a distinct hexagonally shaped synagogue; and the Watts Happening Cultural Center.

Restrained in its design, the Watts Happening Cultural Center has served as a gathering spot for Black artists, musicians, and other creatives who helped reinvigorate the community after the Watts Uprising in 1965. Simple white walls and a structure supported by pillars echo the minimalist tenets of modernism, while a courtyard serves as a dining area and community space for the Watts Coffee House, making the most of the region’s generally warm climate.

Tema Nicole Stauffer // Getty

Harvey Gantt: First Baptist Church-West

Location: Charlotte, North Carolina

Harvey Gantt is a trailblazer in more ways than one. Many people know him for becoming Charlotte’s first African American mayor in 1983, but he also broke barriers as a student of architecture 20 years prior.

In 1963, he waged a legal battle that went all the way to the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, resulting in Gantt becoming the first African American student admitted to Clemson University.

He would later marry the second Black student to enroll, Lucinda Brawley. Gantt graduated with honors in 1965 and went on to earn a master’s in city planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He co-founded Gantt Huberman Architects in 1971 and took on projects like the Charlotte Transportation Center, Johnson C. Smith University Science Center, and the First Baptist Church-West.

The church was Gantt’s first religious commission, which he began working on at 33 years old. The structure combined more traditional elements like warm, red brick with the clean lines of modernist architecture seen in its geometric shapes, descending sanctuary walkway, and more contemporary stained glass windows.

Tema Nicole Stauffer // Getty

Ethel Bailey Furman: Fourth Baptist Church Educational Wing

Location: Richmond, Virginia

Ethel Bailey Furman became the first Black woman architect to practice in Virginia in 1937. Barred from architecture schools, she trained with a private tutor in New York to build her skills and went on to have a career that spanned four decades. Furman designed about 200 buildings of all types, including single-family homes, churches, hotels, department stores, and two chapels in Liberia, Africa.

Among the many religious buildings in her portfolio is the Fourth Baptist Church’s educational wing, representing her mid-century modernist leanings with its large glass windows and streamlined design.

A wife, mother of three, and active community member, Furman encouraged women’s interests in all fields. She also worked with her father, a contractor, designing and building projects throughout her life. Outside of architecture, she participated in Black voter registration drives in the 1960s, attended seminars held by the NAACP on discriminatory housing practices, and co-founded the East End Civic League.

Troy Pumphrey Jr. // Getty

Louis Edwin Fry Sr. and Louis Edwin Fry Jr.: Morgan State University’s Jenkins Hall

Location: Baltimore, Maryland

Louis Edwin Fry Sr. is the first African American to receive a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard University. A founding member of the National Organization of Minority Architects, Fry Sr. mentored hundreds of Black students in architecture. He took on many academic roles in the field, including department chair for architecture at Lincoln University in Missouri and Tuskegee University in Alabama, and he joined Howard University’s faculty in the 1950s.

After leaving Howard University, he founded the architectural firm Fry and Welch. Now run by Louis Fry III, the firm is one of the oldest African American architectural firms still operating on the East Coast. Among Fry Sr.’s projects were the Founders Library and Douglass Hall at Howard University, as well as Morgan State’s Jenkins Hall, which he worked on with his son Louis Edwin Fry Jr.

Fry Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps. He received two undergraduate degrees: one from Howard and another from Harvard University. He then pursued architecture on a Fulbright scholarship in Delft, Netherlands, and earned his master’s of architecture in urban design at Harvard, studying under Walter Gropius. Fry Jr. designed for historically Black campuses like Tuskegee University and urban projects like the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Station.

The father and son’s Jenkins Hall is a Brutalist building featuring a cement-clad façade. Two-by-four windows punctuate the exterior and form a buttress that creates an overhang to prevent the sun’s rays from piercing the lower-level classrooms.

Corey Johnson // Getty

Nathan Johnson: Second Baptist Church of Detroit’s Education Building

Location: Detroit, Michigan

Nathan Johnson was inspired to pursue architecture by the work of Paul Revere Williams, a Black architect who designed lavish homes for the stars during Hollywood’s Golden Age. But Johnson quickly faced discrimination when he attempted to find work at white-dominated firms. Eventually, he began to work in Detroit as a draftsman at White and Griffin, an incubator for Black architects.

In 1956, Johnson opened his practice and became one of Detroit’s most sought-after architects for Black churches, but not without being forced to take secondary positions to larger white firms.

One of his largest and most well known designs is the Brutalist education building for the Second Baptist Church of Detroit, Michigan’s oldest Black congregation. The minimalist structure, made of brick and concrete, blends well with the original church that sits beside it. Its roof, which appears to float over the building, features an open, sheltered garden.

Tema Nicole Stauffer // Getty

Walter Livingston, Jr.: Zion Baptist Church

Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Walter Raleigh Livingston Jr. earned his degree in architecture and his master’s in urban planning from the University of Pennsylvania. Apart from his private practice, he served on the board of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority and was involved in completing Independence Mall and building housing in West Philadelphia.

Livingston also worked on the design of such projects as Progress Plaza, the Clef Club, and the Criminal Justice Center. He was the first Black architect inducted into the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects.

In the 1970s, Livingston designed the Zion Baptist Church, which features colorful glass panels and an abstracted steeple that mirrors the tower of the educational building across the street. Comprised primarily of brick and glass on the outside, the church feels expansive and light, even inside, due to its clerestory walls, which allow generous sunlight to filter in.

Story editing by Jaimie Etkin. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn. Photo selection by Michael Flocker.

![]()