State takeovers of 'failing' schools are increasing, but with little evidence they help students

Joseph Bui for The Hechinger Report

State takeovers of ‘failing’ schools are increasing, but with little evidence they help students

Amarion Porterie, an 18-year-old senior at Stephen F. Austin Senior High School, in Houston

Steve Lachelop stood in front of a hostile audience in Houston, Texas, on the morning of May 18 to ask for help. It was two weeks until the Texas Education Agency, where he’s a deputy commissioner, would remove Houston’s elected school board from their jobs.

In their place would be people hand-picked by agency head Mike Morath, an appointee of Republican Governor Greg Abbott. Lachelop told sitting members they could help the new board by serving as liaisons to the community. “You guys know your communities. You guys have spent, each of you, many years deeply engaging with your communities, and that is incredibly valuable,” he said.

Board member Bridget Wade, a conservative Republican, was skeptical. The Texas Education Agency was taking away board members’ official email addresses starting June 1, she noted, so how could they be liaisons if citizens couldn’t reach them? “That’s a compelling point,” said Lachelop. “Let me go back and do some more thinking on this.”

On June 1, the TEA took over Houston’s school district, removing the superintendent and elected board. Critics say it’s an effort by a Republican governor to impose his preferred policies, including more charter schools, on the state’s largest city, whose mayor is a Democrat and whose population is two-thirds Black or Hispanic. In other districts where state-appointed boards have taken over, academic outcomes haven’t improved. Now red-state governors increasingly use the takeovers to undermine the political power of cities, particularly those governed by Black and Hispanic leaders, according to some education experts.

The Hechinger Report looks at the issue of state takeovers of schools and whether such measures actually aid student performance or are detrimental to Black and Hispanic communities.

Supporters of takeovers say students’ futures are at stake and that the strategies help jolt failing school systems into better performance. Backers of the takeover of Houston Independent School District say it’s needed to improve performance in a few schools in low-income neighborhoods that have a history of poor academic outcomes.

The seeds for the HISD takeover were planted in 2015, with the passage of a state law mandating that the TEA step in if any school in a district were rated academically unacceptable for five consecutive years. Another law passed in 2017 incentivized districts to contract with outside entities, including charter school managers, to assume control of schools that aren’t meeting state standards.

By 2018, four of Houston’s 274 schools, all of them in the city’s economically distressed north and east sides, hadn’t met the standards for four years running, putting the district at risk of a takeover. But at a packed meeting that December, Houston’s board narrowly voted down a proposal to have the district seek bids from outside entities to run the four schools under the 2017 law.

Citizens who spoke almost uniformly opposed the proposal, with many arguing it was the first step in an effort to privatize district public schools. It failed on a 5-4 vote.

On January 3, Gov. Abbott responded with a scathing tweet: “What a joke. HISD leadership is a disaster…. If ever there was a school board that needs to be taken over and reformed it’s HISD.”

The governor would get his wish, but it would take another four years.

[Pictured: Amarion Porterie, an 18-year-old senior at Stephen F. Austin Senior High School in Houston, Texas.]

![]()

Canva

State takeovers of schools, while rare, are not exclusive to Texas

View of a high school hallway

Nationally, takeovers are relatively rare: Between 1988 and 2016, states took control of 114 school districts, about four per year. The first came in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1989 after Republicans gained control of the governorship and state assembly.

Though the first state interventions were by Republican governors, in the 1990s and 2000s education-reform-minded Democratic governors began doing the same, said Domingo Morel, a New York University political science professor who wrote a book on the history of takeovers. Now that’s changed: The Democratic base is pushing back against takeovers, and Democratic governors are now far less likely to support them, said Morel.

In northeast Ohio, for example, community organizers and a Democratic state legislator, Lauren McNally, are pushing to repeal that state’s takeover law. State takeovers in the Lorain, Youngstown and East Cleveland school districts have been a “disaster,” the organizers say. On the latest state report cards, all three got 1 of 5 stars for academic achievement and were ranked near the bottom of districts statewide on that measure.

At least three studies have found that takeovers don’t increase academic achievement. The latest, a May 2021 working paper by researchers from Brown University and the University of Virginia, looked at all 35 state takeovers between 2011 and 2016. “On average, we find no evidence that takeover generates academic benefits,” the researchers concluded.

Takeovers are premised in part on the idea that improving school board governance improves test scores. But the 2021 paper concluded that may be wrong: “These results do not provide support for the theory that school board governance is the primary cause of low academic performance in struggling school districts,” the researchers wrote.

Race, meanwhile, plays a role in the likelihood of a district being taken over. The paper found that majority-Black districts were more likely to be taken over even when their academic performance was similar to that in white districts not taken over. The same was true for majority Hispanic districts, but the effect was less pronounced, said study co-author Beth Schueler.

And takeovers are more likely in states where Republicans control both the governorship and the state legislature, the paper found.

In Texas, Republicans have both, and its state interventions show those same patterns. From 2008 through 2022 the state removed elected boards in seven districts, all but one of which had higher proportions of nonwhite students than the state average. But it’s impossible to draw statistically meaningful conclusions about the role race plays in an individual state like Texas given the small number of state interventions, said David DeMatthews, associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin College of Education.

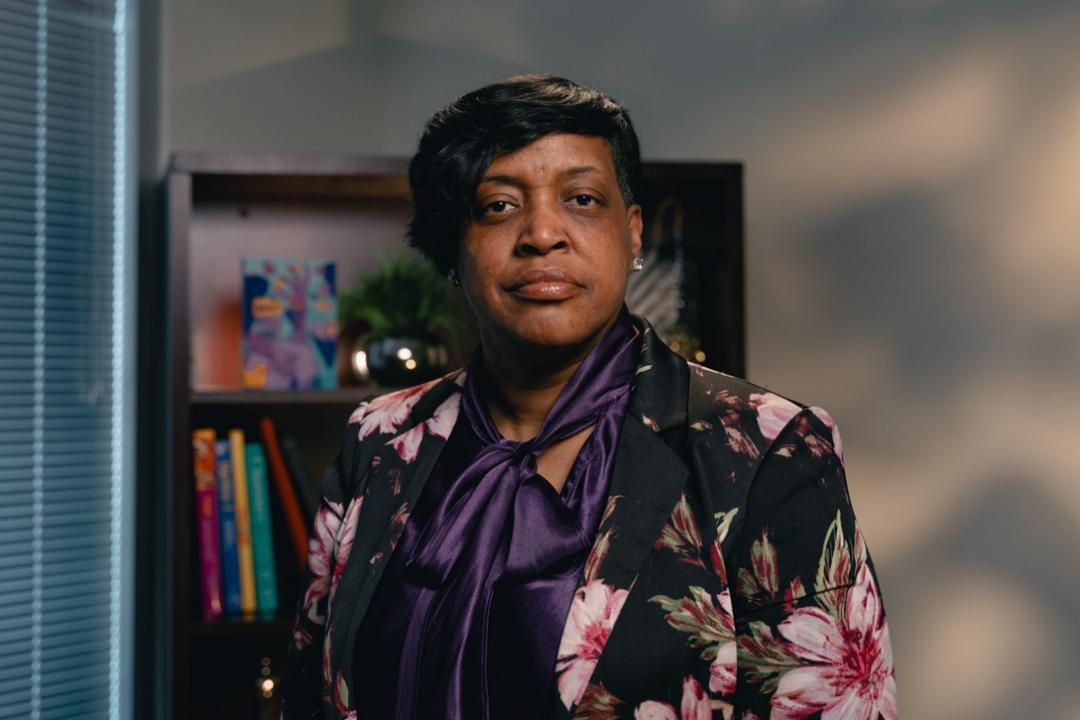

Joseph Bui for The Hechinger Report

In Houston, one high school became an epicenter of the takeover debate

Sabrina Cuby-King, principal of Phillis Wheatley High School

[Pictured: Sabrina Cuby-King, principal of Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas.]

In Houston, by the 2018-19 school year, all but one of the district’s four failing schools was meeting state standards. The exception was 96-year-old Phillis Wheatley High School. It narrowly missed the mark, though district officials pointed to a 2018 technical change the state made in how it calculated school ratings, designed to ensure at least adequate performance in all areas the state measures. That new rule tipped it from a D to an F under an A-F rating system Abbott had signed into law in 2017.

Wheatley sits in a neighborhood of small single-family homes with neat fenced-in lawns on the city’s east side. A poster at the school’s entrance shows the 2017 inductees to its alumni “wall of fame”: NFL player Lester Hayes, surgeon Frank Watson, plus a NASA division chief, a chemist, and others. Congressmembers Barbara Jordan and Mickey Leland, and heavyweight champ George Foreman, all went to Wheatley, too.

In December 2019 Morath, the TEA head, sent a letter to the district announcing that the state was taking over and removing the school board. A key reason, he said, was Wheatley, as well as allegations of misconduct against former HISD board members. The district sued to stop him. Morath had suspended state ratings in 2017-18 for Wheatley and other schools hit hard by Hurricane Harvey, which the district argued had restarted the five-consecutive-year clock set by the 2015 law. Two state courts agreed with the district and granted a temporary injunction while the case worked its way through the courts over three years.

In January 2023, the Texas Supreme Court sided with the state because of a new state law passed in 2021 clarifying that a year in which no rating is given doesn’t stop the count, among other provisions.

But during those three years, Wheatley improved. Its 2019 score of 59, an F, rose to 78 in 2021-22, a high C, during a period when academic outcomes around the country were getting hammered because of the pandemic.

Wheatley principal Sabrina Cuby-King credits several moves for Wheatley’s gains: professional development for teachers on how to fill gaps in student learning caused by COVID, holding teachers accountable for “bell to bell” instruction to wring every minute out of each class, and pairing each student with a teacher or staff mentor. “That keeps them coming to school,” said Cuby-King. “That’s why they feel connected to the campus.” A chart in her conference room shows average attendance up 11 percent over this time last year, to 91 percent.

Administrators closely track individual student data so teachers can intervene if a student’s scores start to flag. The school now dedicates a full period each day to intervention, when students who’ve started struggling get extra help from their own teachers. Individual attention matters more at a small school like Wheatley — each of its 650 students’ scores counts proportionally more toward the school’s accountability rating than at larger schools, said Cuby-King.

Being in the news has motivated students, too. “They started saying, ‘We really need to achieve. We need to show them who we are. We are not what they’re saying we are,'” said former Wheatley social studies teacher Kendra Yarbrough-Camarena.

The school’s 2021-22 accountability score — that C rating — is taped to the building’s glass front door. That, plus large letter “A’s” scattered around the school, are meant to keep students and teachers focused on the goal. “That lets people know that this is a place of academia. This is where we are now [the C rating]. But we’re looking to get from there to an A,” said Cuby-King.

The improvement at Wheatley didn’t dissuade Morath: On March 15, he sent a letter to superintendent Millard House and the board announcing they were being replaced.

Public reaction was furious. Citizens interrupted information meetings the agency held in March to explain the mechanics of the intervention. The teachers union, the mayor and area legislators held a rally to protest the move. Hundreds of students walked out.

“I’ve not talked to a single student or teacher who’s for the takeover,” said Amarion Porterie, an 18-year-old senior at Stephen F. Austin Senior High School.

Morel, the New York University professor, said Texas’ move may be a sign that Republican governors intend to use district takeovers more often. “They may be weaponizing state takeovers in ways that they didn’t before and making it more obvious, in my view, what their intentions are,” he said. “The reason I say Houston might be pointing in this direction is because the Houston school district itself is not struggling.”

He sees the Houston intervention as of a piece with other types of red-state takeovers like Mississippi’s expansion of state police jurisdiction in majority-Black Jackson, Michigan’s takeover of Flint, and Georgia’s attempt to assume control of the election board in Fulton County, where Atlanta is located.

In 2021-22, the district earned an overall score of 88, a high B — better than more than a hundred other Texas districts, state data show. On that score the Brown University paper offers a warning: the higher-achieving the district, the more negative the effect of the takeover, Schueler said their data show. “Takeover can be a very disruptive intervention,” said co-author Joshua Bleiberg by email — because, for example, teacher collective bargaining agreements can be revoked and teachers and district staff dismissed, he said.

In Houston, some blame the district, not the state. Sue Deigaard, a board member from 2018 until she was removed June 1, said that after the 2015 law passed, if the district and board had “hyper-focused” on the lowest-performing schools like Wheatley, “you and I wouldn’t be talking.” She believes in local democratic control, she said. “But I think what I’m most angry about in all of this is we had the power to prevent this.” Instead, she said, the board got distracted by a bitter dispute between its members over who should lead the district as superintendent.

Joseph Bui for The Hechinger Report

Houston takeovers have caused major changes for teachers and staff, as well as students and their families

Houston ISD school building

And area state legislator Harold Dutton, a Democrat and Wheatley graduate, wrote the language in the 2015 law authorizing takeovers of a district if one of its schools fails for five years running. He told local outlets that he doesn’t regret creating the provision, though he never thought a takeover would happen in Houston because the district would fix Wheatley. “It’s HISD’s responsibility to educate students, and when they let them fail they should be punished,” he said in March. (Dutton didn’t respond to several requests for comment for this article.)

As the Morath-appointed board moves in, it has a clean slate. The elected board is gone. Superintendent Millard House had already left May 26, and at least five people in his cabinet had already resigned too. Jackie Anderson, president of the Houston Federation of Teachers, said many teachers have told her they’re not planning to return for the next school year because of the state’s move. On June 1, Morath appointed Mike Miles, a former superintendent of Dallas’ school system and the CEO of a charter school network, as the new superintendent, and named the nine members of his board of managers.

If that means more charters are coming, Houston parent Anna Chuter is worried. Her son is in the special education program at Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School on the city’s north side, and she is a teaching assistant there. State rules allow charters to deny admission based on student discipline records, and they serve smaller proportions of students with disabilities than do the state’s traditional public schools, according to a 2019 analysis by Houston Public Media. She fears lower-performing traditional schools being turned into charters and the remaining traditional schools like Roosevelt being forced to absorb more kids in special education. (While the district itself has no district-authorized charters, 100 charters operate inside the boundaries of the district under direct state authorization, according to TEA spokesperson Jacob Kobersky.)

Since taking charge, Miles has made a number of dramatic moves, including overhauling 29 schools, Wheatley among them, by requiring all staff to reapply for their jobs and instituting a pay-for-performance plan for teachers at those schools that’s linked to test scores. Libraries in those schools are being turned into centers where students considered disruptive will participate remotely. And Miles has slashed the number of central office positions by almost 25 percent.

Under state law, it will be at least five years before Houston gets back its full elected board, and it could be far longer. In his March 15 letter, Morath said one condition of ending the takeover was “no more multiyear failing campuses” — meaning none of its 274 schools may fail state standards for more than a single year running. State agency spokesperson Jacob Kobersky confirmed that provision exceeds the requirements of the 2015 law that triggered the takeover. “The criteria that TEA is outlining would allow it to effectively control HISD indefinitely,” said Ashley Harris of the Texas ACLU.

The state education agency says that its past takeovers have had mostly positive academic outcomes: In six of the seven districts in which it’s intervened since 2008, academics improved, according to an online agency presentation arguing for the Houston intervention. Outside Waco, the town of Marlin’s school district, which has just three schools, saw its district rating improve from an F to a B since the state took over in 2019.

DeMatthews, at UT Austin, is skeptical. “The agency has taken over mostly small districts, some of them very tiny districts, that can be really dysfunctional,” he said. “You might have a couple of school board members who are not doing a good job and a superintendent who’s not watching the books.” That’s quite different from taking over a large district like Houston’s, he said. The district has 27,000 employees and 189,000 students.

Takeover opponents say they’re not done resisting. In March, the Texas ACLU petitioned the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the replacement of Houston’s board as a violation of the federal Voting Rights Act. A parents group organized a protest before the replacement board’s June 8 meeting.

Some former elected board members aren’t in a mood to help either, Lachelop’s May 18 request aside. Elizabeth Santos is a former English teacher in the district who served on the board from January 2018 until she was replaced on June 1. In 2021 she’d won a close race to retain her seat. Now the person she defeated in that election, Janette Garza Lindner, serves on the replacement board after being appointed by Morath.

Sitting in her office for the last time on May 18, Santos had a warning: “My students are going to come back together, and we’re going to put on our walking shoes and knock on doors. Our job is to remove this governor and to expel this agency. That’s where I’m at.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.