Educators and families are divided on banning phones in classrooms. Is locking up phones the solution?

Photo Illustration by Stacker / Canva

Educators and families are divided on banning phones in classrooms. Is locking up phones the solution?

cell phone screens appear behind chain link fence illustration

Business is booming at Yondr, a company that produces neoprene pouches to lock up students’ cellphones — a clear sign that the movement to keep phones out of classrooms is spreading across the U.S.

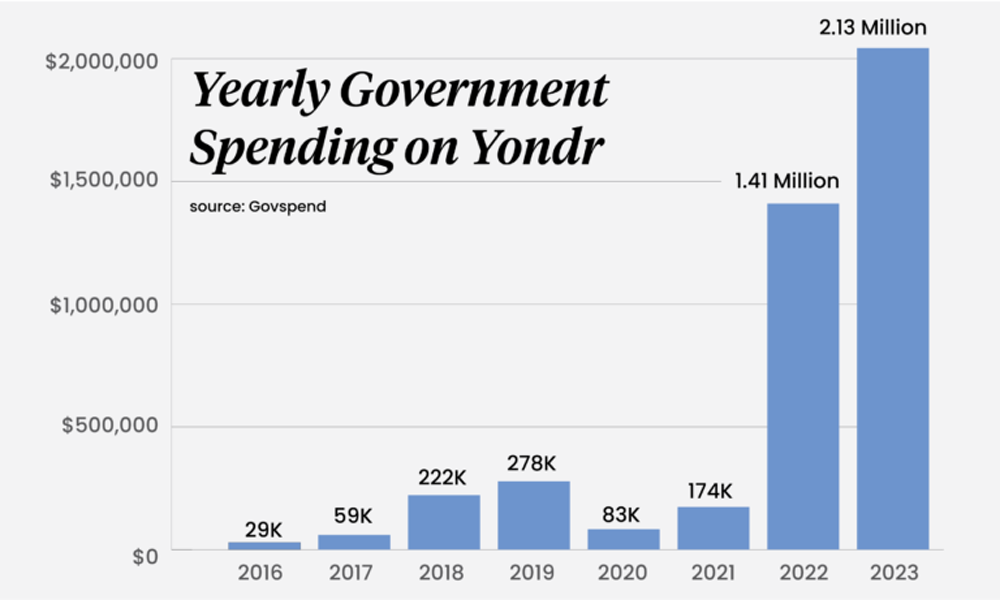

Since 2021, the company has seen more than a tenfold increase in sales from government contracts, primarily with school districts — from $174,000 to $2.13 million, according to GovSpend, a data service. The Holyoke, Massachusetts, and Akron, Ohio, districts are among those requiring all middle and high school students to slip their phones into the rubbery envelopes each morning and unlock them with a magnet at the end of the day.

“All signs point to 2024 being even busier,” said Sarah Leader, the company’s spokeswoman. With an estimated 2,000 schools using the pouches this year, the company has doubled in size to 80 employees to meet the demand.

“It’s a game changer,” said Patricia Shipe, president of the Akron Education Association. She worked with district leaders to pilot and then adopt the Yondr system this year. Students are less distracted and schools feel calmer, she said. “The transitions between classes are faster because kids are not on their phones.”

The 74 takes a closer look at how school district sales have boosted the student cellphone storage company’s business—and what it means for classrooms across the country.

![]()

The 74 / GovSpend

Cell phones: distractions or essential life lines?

chart showing government spending on products to lock up student cell phones

Most districts already prohibit students from using phones in class for non-academic reasons. But phone-free advocates say tighter restrictions are necessary to refocus students on learning following the pandemic and to minimize the negative impact of social media on students’ mental health.

Such moves typically draw strong reactions. Some parents see phones as integral to staying in touch with their children during emergencies.

But many welcome the opportunity to curb frequent disruption. Teens report being on social media “almost constantly,” according to new data from the Pew Research Center. Efforts to break their habit, at least during school hours, could get a critical boost if Congress passes a bill that would create a $5 million grant program to cover the costs of “secure containers” like Yondr or wall-mounted phone lockers.

“Widespread use of cellphones in schools are at best a distraction for young Americans; at worst, they expose schoolchildren to content that is harmful and addictive,” Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, a Republican, said in a statement about his bipartisan proposal with Sen. Tim Kaine, a Virginia Democrat. “Our legislation will make schools remain centers of learning.”

Congress would still need to approve funding for the program. The legislation also directs the Education and Health and Human Services departments to study the impact of cellphone bans on student achievement, mental health and behavior.

A ‘security nightmare’

Getting student violence and bullying under control is one reason the Akron school board approved its $180,000 agreement with Yondr in June for 10,446 pouches. Leaders hope locking up phones during the day will halt a troubling pattern of students not only using them to arrange fights on social media, but record the altercations on video.

“It was happening daily in our buildings and multiple times a day,” Shipe said. As in many districts, physical attacks against teachers had also increased. “It was just a real security nightmare.”

Many students have rebelled against the changes. And Shipe warned that opposition to losing what she described as “an appendage” for most teens “gets worse before it gets better.” Online discussion threads among students include ways to destroy the pouches, and demonstrations on TikTok show how bending the magnetic closure prevents them from locking.

But as Shipe notes, those who sabotage the pouches typically keep their phones hidden during class, if only to avoid getting suspended.

“There are just a lot of positives,” she said.

Are phone bans sending a ‘mixed message’?

Many researchers and advocates agree that school phone bans have more benefits than drawbacks. In October, nearly 70 child advocates, educators and mental health experts sent Education Secretary Miguel Cardona a letter asking him to urge schools to adopt phone-free policies. Late last month, an author of the letter met with a senior department official, but didn’t get the response she wanted.

“The secretary does not intend to act on our phone-free schools letter,” said Lisa Cline, part of the Screen Time Action Network, a coalition focused on limiting children’s use of digital devices.

Cardona has yet to reveal his opinion on banning phones, but he’s frequently mentioned the role social media plays in the mental health problems facing students. In March 2023, Cardona said media companies should be held accountable for “the experiment they are running on our children.” Two months later, the White House announced that the department would work with other agencies to issue model policies for districts on phone use.

An Education Department spokesman said officials are still preparing that guidance and are working “in close partnership” with Surgeon General Vivek Murthy on the issue.

Under the Senate bill, districts would need to get feedback from parents on cellphone restrictions before applying for funding, and the bill directs Cardona to choose grantees that will “likely yield helpful information” on the impact of phone bans. The program also would allow exceptions for students with disabilities and those who need phones for translation apps or to treat health conditions.

While Yondr’s growth is one piece of evidence on the trend, a 2022 survey pointed to the popularity of phone bans among parents. In a sample of nearly 11,000 parents with a child in school, 61% agreed with getting phones out of the classroom. The National Parents Union is currently collecting more data on the issue, but the stance of its president, Keri Rodrigues, is firm.

“The data is clear,” she said. “[Phones] should absolutely be banned during the school day. Every parent I talk to has agreed.”

International research points to higher test scores when phones are out of sight, and some educators say students tune in to class more when they’re not scrolling on social media. In Massachusetts, where Rodrigues lives, the state education department already awards grants for districts that clamp down on use, and Commissioner Jeffrey Riley has hinted at expanding the program.

But some parents aren’t on board.

“Parents are afraid because of school shootings,” said Melissa Erickson, executive director of Alliance for Public Schools, a Florida nonprofit that aims to inform parents about education policy. “That’s a statement of the times.”

She called those in favor of strict bans “tone deaf” to the way students socialize. Kids depended on devices to stay connected to friends and teachers during the pandemic. Banning them, she said, sends a mixed message.

“We told them that one-to-one is everything and now we’re taking it away,” she said.

Yondr

‘The extreme end’

Florida has gone further than any state to curb use during school hours. Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation in May that prohibits students from accessing social media, especially TikTok, and from using phones except when teachers approve their use for educational purposes.

Districts, however, have some discretion. After instituting limits on use during class this year, Pasco County Schools Superintendent Kurt Browning is calling for a complete ban by the 2024-25 school year. The Hillsborough district board adopted a policy that allows students to keep their phones if they are “powered down, silenced, and stored out of sight unless authorized by staff.”

Last year, teachers tended to set their own rules, said Kendal Coulbertson, who graduated in May from Armwood High in Hillsborough. Some teachers, she said, didn’t mind if students used their phones as long as they were turning in their assignments and getting good grades.

But she thinks a ban goes too far.

“I was engaged in conversation. I was engaged in learning, and I think, honestly, that should be the goal rather than going to the extreme end,” she said. She added that guns in school are a “real issue” and students want to be able to reach their parents in case of an emergency. “There could be some type of middle ground.”

Like parents, educators are split on the issue. In some districts, including Akron and Florida’s Orange County, bans on phones extend through lunch, a time when teens typically check in with social media.

“It has to be all or nothing,” said Shipe, the Akron union leader. Teachers, she added, shouldn’t have to haggle with students to lock their phones back up after lunch.

Enforcement was a daily struggle for Dina Hoeynck, a former teacher in Cleveland who taught graphic design. At her school, students had access to their phones between class periods and teachers were in charge of ensuring they were locked up — a system she described as “impractical.”

“Going through the rigamarole of having students lock their phones at the start of class and unlock them at the end felt like a massive waste of time,” said Hoeynck, who kept needle nose pliers on hand to straighten pins on pouches when students bent them. “It led to a significant loss of instructional time and created unnecessary power struggles between teachers and students.”

Mark Benigni, superintendent of Connecticut’s Meriden Public Schools, is among those who oppose a blanket policy,

“We must educate our students on the appropriate and effective use of cellphones as we do for all technology,” he said. “We also need to recognize that today’s cellphones offer numerous opportunities to enhance learning, organization and communication. Many students are emailing teachers using their cellphone and district-provided emails.”

Benigni happens to be Cardona’s former boss. Before President Joe Biden tapped him to be secretary, Cardona served as assistant superintendent in Meriden until becoming Connecticut’s education chief. While the district didn’t pass its cellphone policy until April 2021, Benigni said it closely follows practices in place when Cardona worked there: Students can’t use phones during instructional time unless a teacher permits it or if they’re necessary to access the district’s online learning platform.

“The secretary always supported the safe use of technology when he was here,” Benigni said. “There are times when teachers need to have students put them away.”

This story was produced by The74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.