When salt was gold: The evolution of two commodities

Photo Illustration by Stacker // Getty Images

When salt was gold: The evolution of two commodities

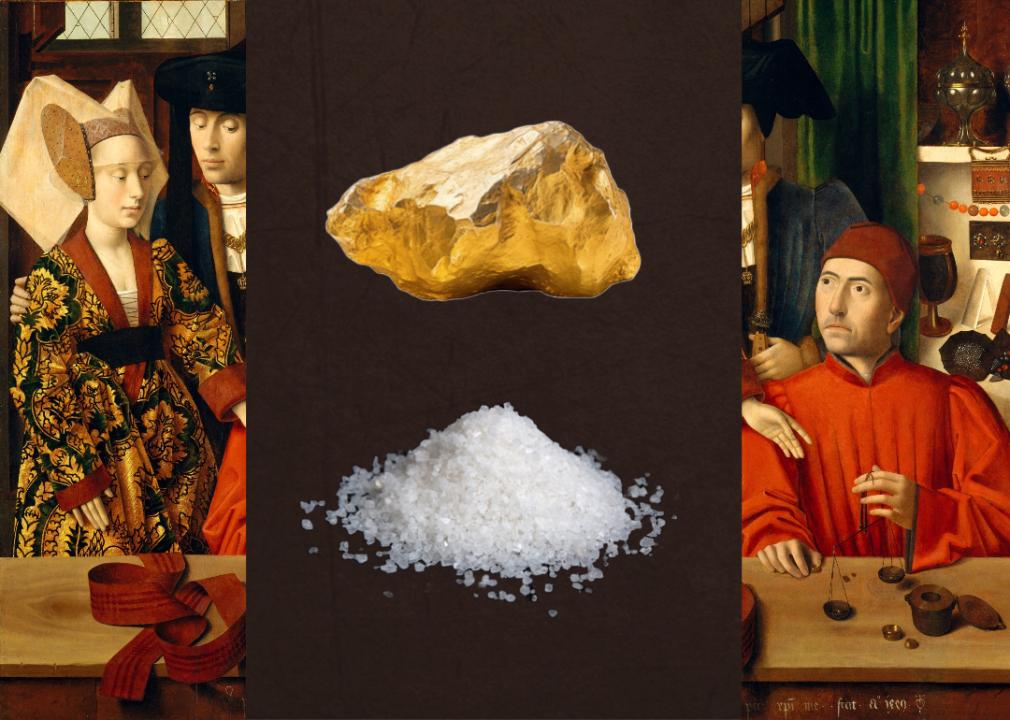

Photo illustration with images of salt and gold and a Petrus Christ’s painting “A Goldsmith in His Shop”.

An ounce of salt could once be traded for an ounce of gold. Now, the idea is laughable, with the cost of gold reaching over $2,000 per ounce while 26 ounces of salt is valued at just $1. How did gold skyrocket while salt became commonplace?

SD Bullion researched the history of these two commodities, from their convergence in value long ago to the significant modern-day difference in cost between the two.

A brief history of salt

Although it may sit on dining tables worldwide today, salt was not easy to find centuries ago. Animals forged paths in search of salt licks, which humans then turned into roads, causing communities to grow. As human diets broadened from naturally salty game to include grains and other forms of sustenance, salt was needed to supplement diets and preserve food. As far back as 2700 B.C., it was also used medicinally in China and was a common antiseptic in ancient Rome.

Egyptian art dating back to 1450 B.C. depicts the practice of salt making. The oldest method is evaporation, allowing the sun to dry pools of seawater, leaving salt crystals behind. The second method is mining veins, or dome-shaped deposits, of the mineral found thousands of feet below the earth’s surface.

Salt was a status symbol through medieval times and beyond. Well into the 18th century, important dinner party guests were seated at the head of the table, closer to the salt. The mineral was also highly regulated and taxed in countries like France and Britain—in fact, outrage over salt taxes was one cause of the French Revolution.

A brief history of gold

Gold has shaped global civilization since ancient times. In 4000 B.C. Eastern Europeans began creating decorative objects with it, and gold jewelry has been excavated from ancient Egyptian tombs. It was used as Chinese currency as far back as 11th-century B.C. and later in the Roman Empire, beginning around 50 B.C.

Gold has become increasingly desirable over the years. In the late 1300s, Great Britain shifted its economy to a system based on silver and gold. The first U.S. gold coin was produced in the late 1700s, and by the mid-1800s, the country was in a frenzy over the California Gold Rush. With most countries using the gold standard to set their currency’s value, gold remained a part of global economies until after World War II.

This mineral has never been easy to find and process, though, making it a valuable resource. It can take up to 10 years to determine if a potential site can be mined, then another one to five years for planning, permitting, and construction. Only then can the ore be extracted and processed to sell, with mines operating for just 10 to 30 years before they are depleted.

When salt and gold were equals

Centuries ago, salt was not readily available worldwide—finding salt on the earth’s surface was rare, and mining capabilities were limited—so many depended upon trade to obtain this dietary necessity. Dating back to the 6th century, salt and gold were considered equal in value. Sub-Saharan African merchants, including the Akan people of West Africa and the kingdom of Ghana, leveraged their access to gold by trading an ounce of this precious metal for an ounce of salt.

These trade routes spanned the globe, crossing the land from Venice to Constantinople and the sea from Egypt to Greece. One of the busiest roads leading to Rome was named the Via Salaria, meaning “the salt route.” In certain areas of Africa, salt was so valuable it was pressed into cakes and used as currency.

How did the values of salt and gold diverge?

In short, it’s a simple issue of supply and demand. Over time, salt production has increased, making it more readily available and thus causing the price to drop. According to Statista, the production of salt in 2022 was a whopping 290 million metric tons, with the U.S., China, and India leading production.

In contrast, the lengthy process required to mine gold has driven the price of this precious metal higher. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the total amount of gold that has been discovered worldwide is just 244,000 metric tons—a fraction of the salt produced in a single year. As a result of this limited supply, demand for gold has tripled since the 1970s.

Despite these divergent price points, the consumption of both commodities remains high today, with the bulk of salt used for keeping wintry roads clear and nearly half of mined gold used for jewelry.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Paris Close.

![]()