What it would really take for US drivers to go fully electric

Aliaksei Kaponia // Shutterstock

What it would really take for US drivers to go fully electric

A row of four electric cars getting recharged at an EV charging station.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently finalized stringent national emission standards for 2027–2032 model-year vehicles. The ruling aims to drive electric vehicle adoption and reduce light-duty vehicle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 50% and medium-duty vehicle emissions by 44% compared to 2026 models.

Automakers, dealers, and advocacy groups are pushing back, raising concerns over EV transaction prices, energy generation requirements, and necessary electrical grid infrastructure changes — and they’re not alone.

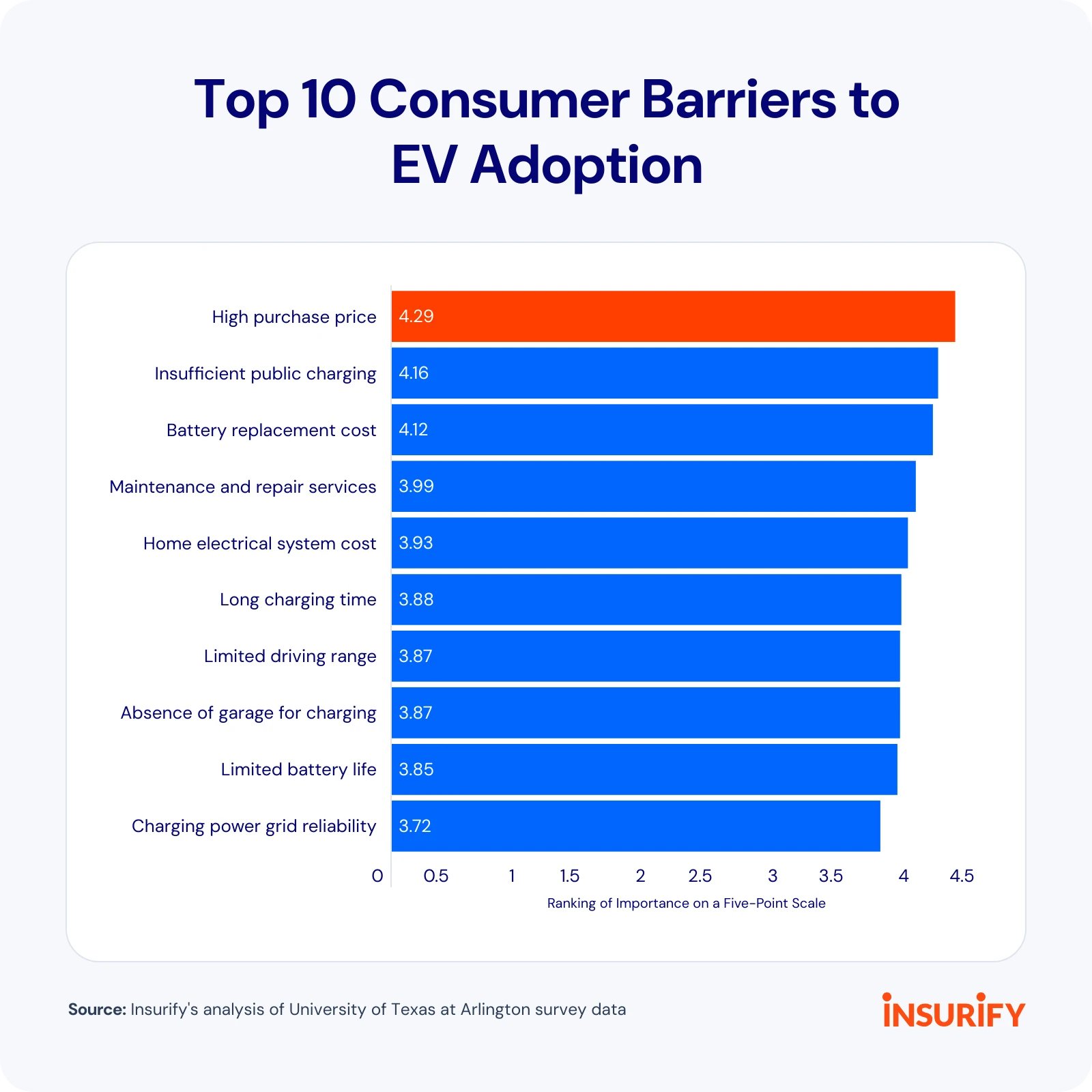

Some consumers share this apprehension along with concerns about high battery replacement costs and access to maintenance and repair services, according to a University of Texas at Arlington Survey.

Transitioning to an all-EV future will take a collective effort to address consumer, environmental, economic, and infrastructure concerns — but the long-term benefits could improve human health, drive green-energy innovations, and mitigate climate change.

To find out what it would take to get American drivers to go fully electric, Insurify analyzed the main barriers to EV adoption and asked industry experts to weigh in with their solutions and predictions.

Key takeaways

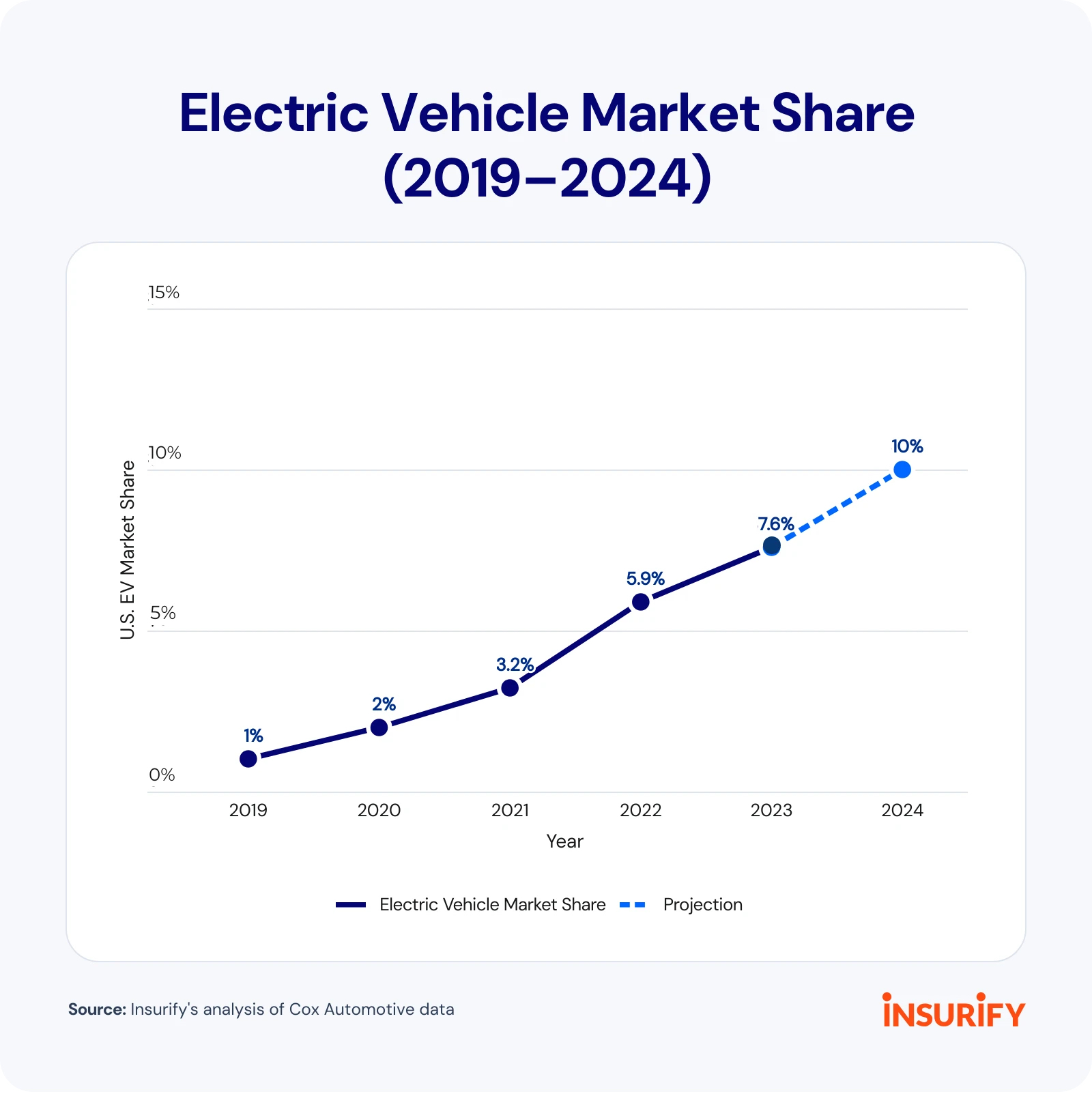

- Under new EPA emission standards, a projected 56% of new vehicle sales will be electric by 2032. EV sales accounted for less than 8% of sales in 2023, according to Cox Automotive.

- Car insurance for EVs costs about 20% more than for traditional vehicles. Full coverage for gas-powered vehicles costs an average of $210 per month, compared to $251 for EVs.

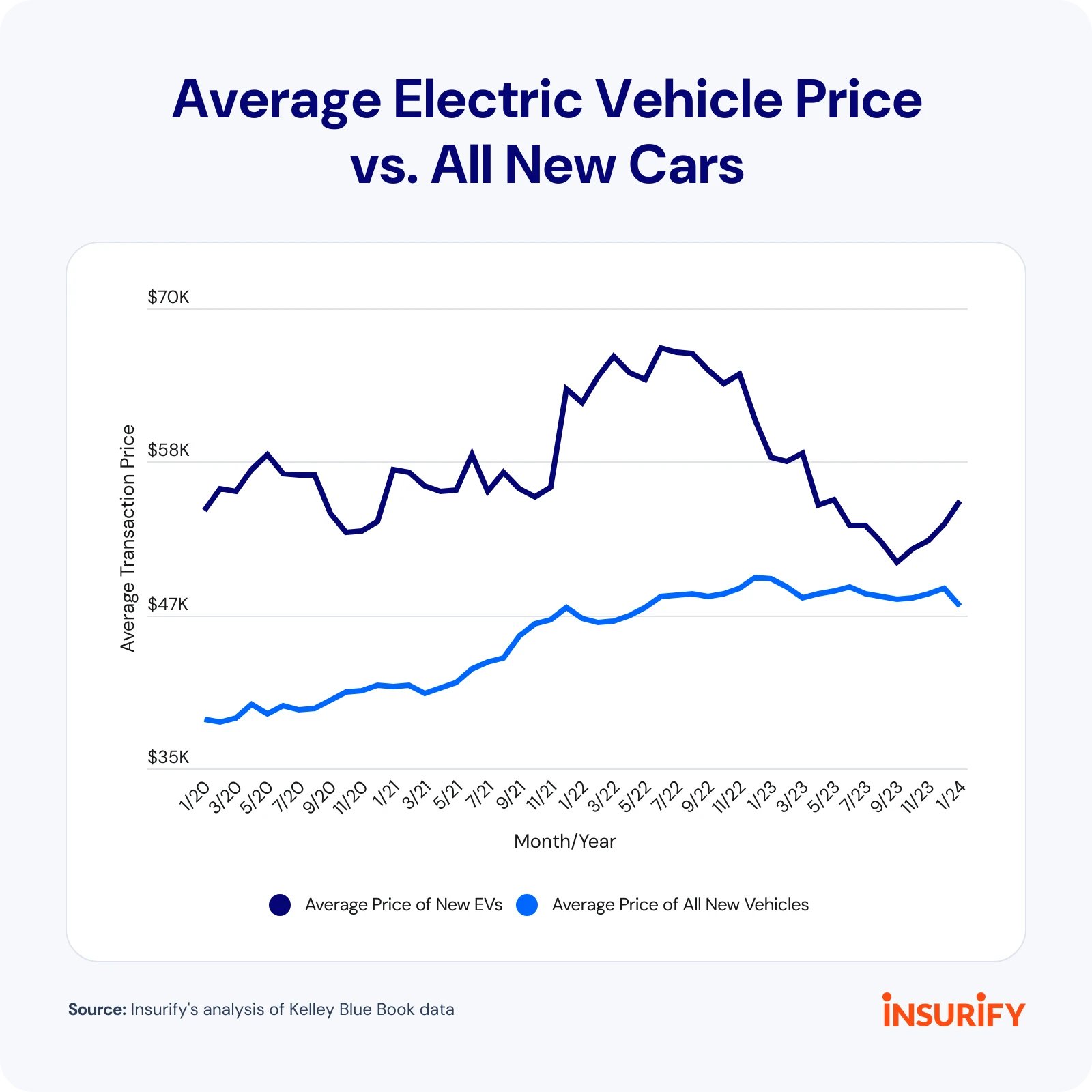

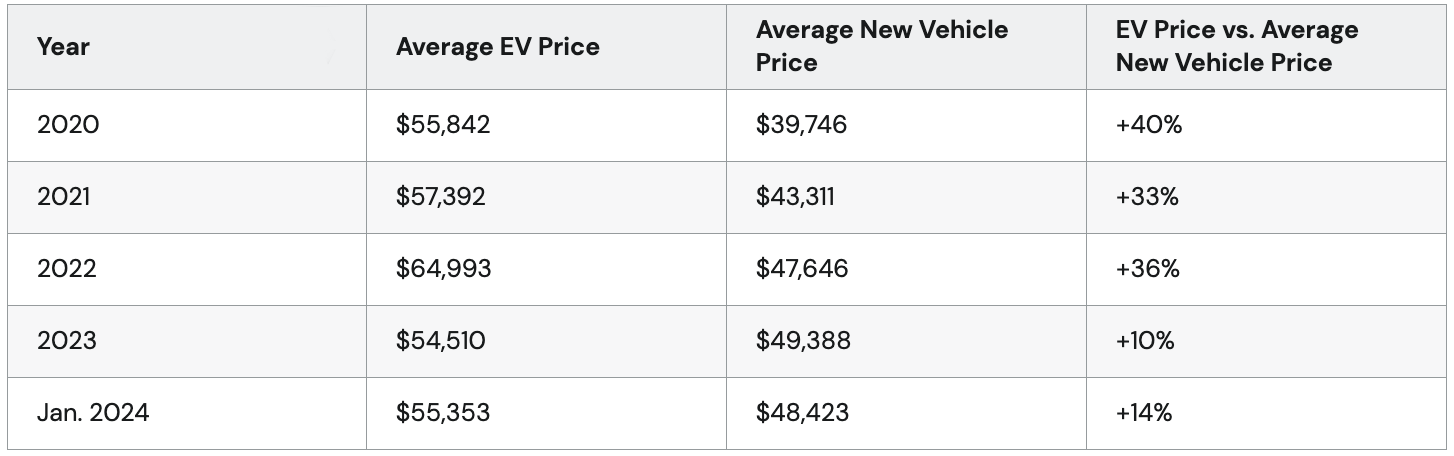

- EVs cost an average of $55,353 — 14% more than the average transaction price for all new vehicles, according to Kelley Blue Book (KBB).

- Consumers rate high transaction prices as the top barrier to EV adoption, followed by insufficient public charging infrastructure and battery replacement costs, according to a 2023 survey from the UTA.

- Reaching 100% EV sales by 2035 and using clean energy could prevent more than 89,000 premature deaths by 2050, according to the American Lung Association.

![]()

Insurify

Where U.S. EV adoption currently stands

Image showing linear graph results of EV market shares from 2019-2024.

EV sales have overwhelmingly surpassed past projections, increasing from just 1% of vehicle sales in 2019 to 7.6% in 2023. A record 1.2 million drivers bought EVs in 2023, according to KBB. The segment will hit a 10% market share in 2024, according to Cox Automotive’s forecast.

Sales have slowed from a 52% year-over-year increase in 2022 to 40% in 2023, but despite the slump in demand, EVs are on track to meet U.S. climate goals.

Recently passed legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act will accelerate the pace of net greenhouse gas emission reductions by 29%–42% by 2030, thinktank Rhodium Group predicts.

But while EVs advance toward emission targets, clean energy is falling short. Plus, the current pace of charging network growth can’t keep up with EV sales, Siemens Financial Services notes.

Insurify

Consumer barriers to EV adoption

[Image showing graph results of the “Top 10 Consumer Barriers to EV Adoption”.

Reaching 100% EV adoption will require addressing consumer barriers. Car buyers ranked top deterrents to EV adoption in a UTA study, “Evaluation of barriers to electric vehicle adoption: A study of technological, environmental, financial, and infrastructure factors,” which included the following barriers.

- Technological: Limited driving range, long charging times, limited battery life, poor safety, doubts about reliability, and fewer EV models.

- Environmental: Problems of battery disposal and environmental effect of battery production.

- Economic: High purchase price, high battery replacement cost, high electricity price for charging, lower resale value, and adaptation cost of electrical system at home.

- Infrastructure: Insufficient public charging stations, charging problems in the absence of a garage, insufficient maintenance and repair services, and low reliability of the charging power grid.

Consumers identified high purchase prices as their top barrier to buying an electric car.

Insurify

Roadblock: EV prices are higher than gas-powered cars

Image showing linear graph results of “Average EV Price vs. All New Cars”.

The average transaction price for new electric cars was $55,353 in January 2024 — 14% more than the average for all new vehicles, according to KBB. As gas-powered vehicle prices have surged, the gap in prices has reduced from 40% in 2020 to 10% in 2023, but EV prices have only dropped by $489 on average.

Insurify

Solution: Cheaper batteries, competition, and tax credits reduce EV cost

Table showing from years 2019-2024 the comparison of the average prices between an EV, new vehicle and their new price.

While the cost of barriers is currently high, declining battery costs over the next five years could reduce the barrier to EV ownership, according to Kenneth Gillingham, senior associate dean at the Yale School of the Environment and professor of economics at Yale University.

As EV production increases, lithium-ion battery prices will drop to $80/kilowatt-hour (kWh) by 2030 — a 57.5% drop from record-low 2023 prices, research organization BloombergNEF predicts.

“There are other important barriers, too, though, such as a lack of EV offerings in many vehicle segments,” says Gillingham. “Most EVs are still best categorized as ‘luxury vehicles.’ This, too, is likely to change in the near future.”

Cox Automotive estimates consumers will see more than 70 EV options within the next two years, compared to 40 available models in 2023.

More used EVs could bring down costs for consumers, too. The used-EV market is still small compared to gas-powered cars, but it’s growing. In 2024, used EV sales could increase by 40% over 2023, the used-EV information startup Recurrent predicts.

Tax rebates also promote adoption by lowering the cost of EVs. Many EVs qualify for a credit of up to $7,500 under the 2022 IRA. But new battery component requirements, aimed at reducing reliance on materials from China, made many models ineligible for the full incentive. IRA tax credits may need to extend past 2030 to avoid decreased EV demand.

Insurify

Roadblock: EVs cost 20% more to insure than gas-powered cars

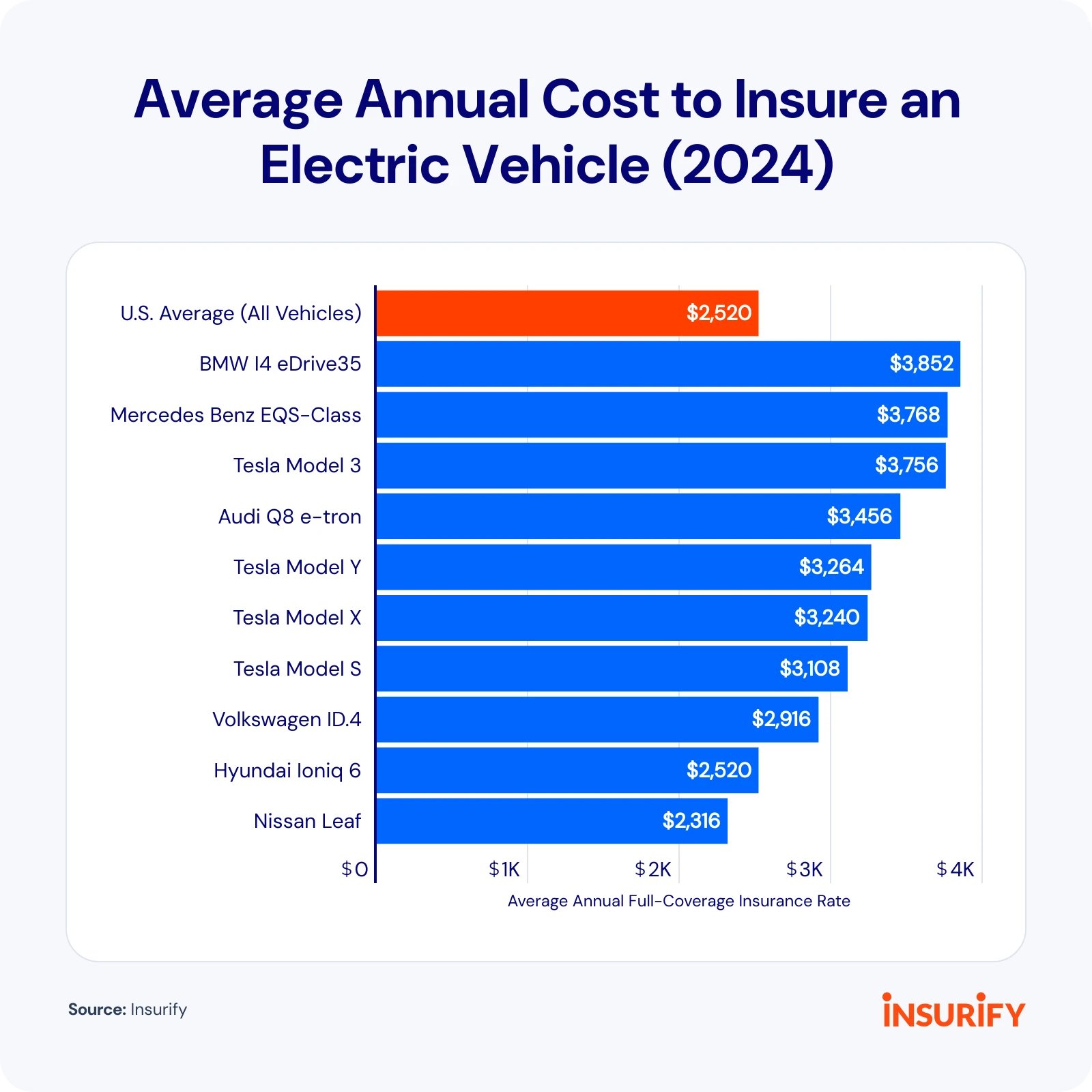

[Image showing the “Average Annual Cost to Insure an EV” in 2024.

Car insurance prices increased by 24% in 2023, and Insurify projects prices will rise an additional 7% throughout 2024. Full-coverage insurance for an EV costs an average of $3,012 per year, compared to $2,520 for all vehicle models. With higher transaction prices already a top concern for consumers, insurance rates present an additional cost barrier to EV adoption.

“EVs have a higher cost of repair due to specialized parts and components, with the battery being a prime example,” says Jacob Gee, an insurance agent and quality assurance specialist. “EVs often require specialized knowledge and training, which can also drive up the cost of repairs.”

The average cost of a repair claim for EVs is $6,018, compared to $4,696 for internal combustion engine (ICE) alternatives (28% higher), according to Mitchell International, a claims management and repair estimate software company. Labor makes up 50.4% of EV repair costs, compared to 41.77% for traditional ICE vehicles.

Higher repair costs mean more expensive claims for insurance companies, which increases the average cost to insure an EV.

Tesla launched an insurance unit in 2019, promising to offer “vastly better” coverage to Tesla drivers than other auto insurers. But the all-EV automaker now faces a class-action lawsuit from drivers who say Tesla Insurance overcharged for premiums based on sporadic vehicle crash warnings instead of their actual driving.

Solution: Lighter, safer, lower-priced EVs reduce coverage costs

EV drivers could see lower insurance rates as more non-luxury options enter the market. Full coverage for a Nissan Leaf, which retails for about $28,000, costs an average of $193 monthly. Tesla’s most affordable model, the Model 3, starts at just under $39,000 and has an average monthly full-coverage rate of $313.

Lower EV transaction prices would reduce the cost of replacing an EV, but insurers also factor in the price of repairs. EVs will be cheaper to produce than comparable ICEs by 2027, but the cost to repair an EV body and battery after a serious accident will increase by 30%, Gartner, a technological research and consulting firm, predicts.

Higher repair and battery costs mean insurers are more likely to write off EVs as a total loss compared with ICEs, says Gee. As of now, EVs are totaled at the same rate as gas-powered cars.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) have expressed concerns about collisions between heavy EVs like the GMC Hummer EV, with a gross vehicle weight rating of 10,500 pounds, and lighter gas-powered cars like the Honda Civic, which weighs about as much as the Hummer’s 2,900-pound battery pack.

Heavy EVs like the 7,000-plus-pound Rivian R1T truck tore through guardrails in crash tests by the Midwest Roadside Safety Facility at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. A 2018 Tesla Model 3, which weighs approximately 4,000 pounds, lifted the guardrail and passed under it.

Reducing the weight of EVs could lower accident severity and insurance costs. The IIHS recommends automakers design heavier EVs with additional crush space to compensate for the effect of extra weight in a crash.

Insurify

Roadblock: EV batteries have limited range and high replacement costs

Image showing the “EV Battery Range” from 2011-2023.

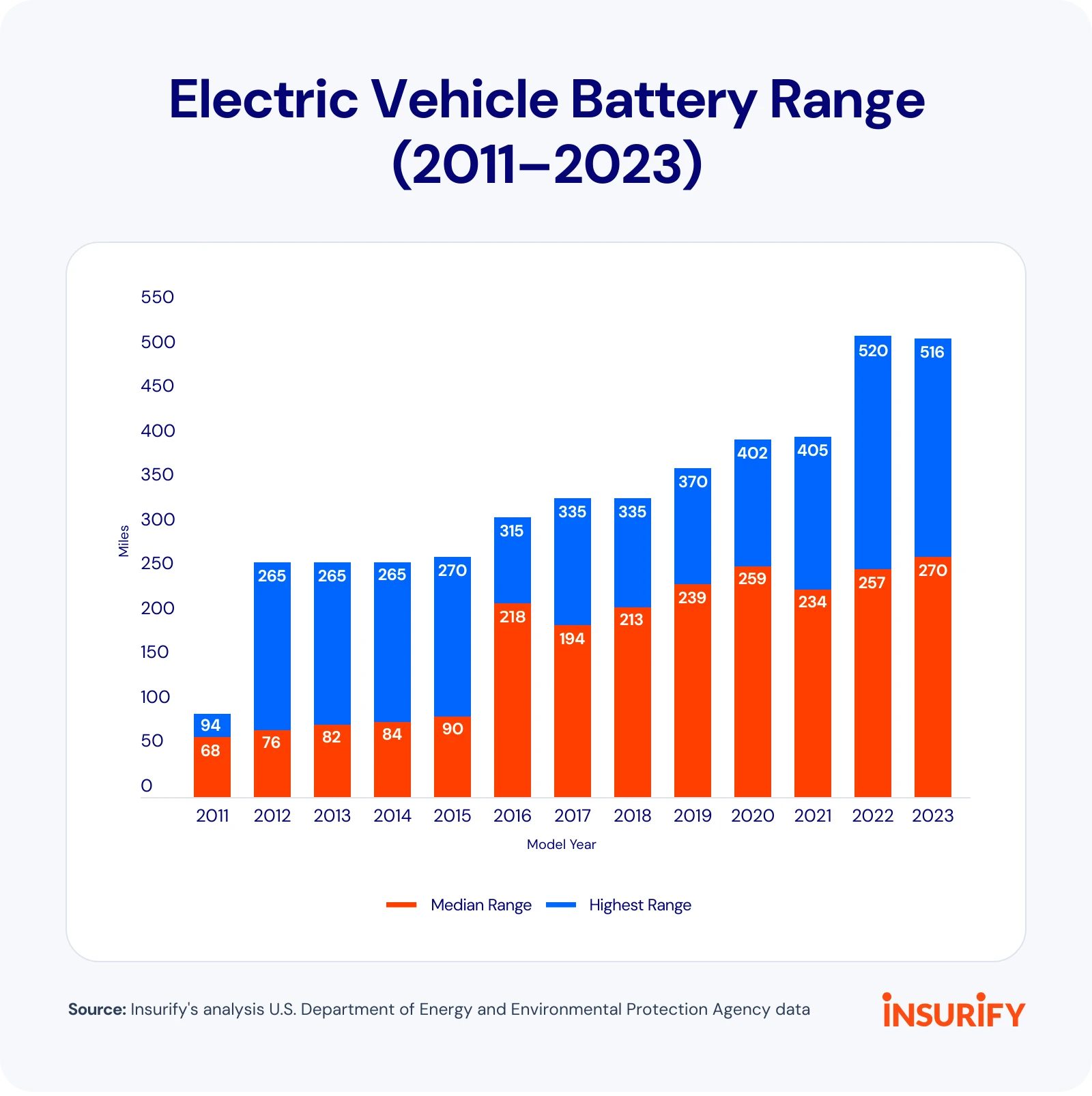

The median EV range has increased nearly fourfold since 2011, according to U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and EPA data, lessening range anxiety for some consumers. But drivers still rated battery range as their seventh-most important concern about going electric in a 2023 UTA survey. Battery replacement costs ranked third, and limited battery life placed ninth.

The cost of EV battery packs declined by 89% between 2008 and 2022, according to the DOE. Still, replacements range from $6,000 to $20,000, Recurrent reported.

EV charging speeds have also improved, but the amount of time required for charging compared to filling up a gas tank is still a deterrent. Direct-current fast charging (DCFC) can charge an EV to 80% in 20 minutes to an hour.

Solution: Battery advancements increase charging speed and lower costs

Battery technology will improve, says Gillingham. “The technology for charging very fast, [in 10 minutes], is much closer to commercialization, and ultralong-range EVs are very possible, but not at an affordable price any time soon.”

Gillingham expects to see more modular EV designs, which could lower costs and scale production through sharing components across multiple vehicles. He’s also excited about the potential for solid-state batteries.

“If they could be built affordably, this would open the door to very fast charging and higher energy densities, which could allow for longer ranges on smaller batteries.”

But solid-state batteries, like lithium-ion, will take time to hit the market and face a potential “production hell,” warns the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). Automakers are still betting on the technology. Volkswagen Group’s battery company is testing lithium-metal cells, and Toyota teased ultralong-range EVs with solid-state batteries by 2027.

Roadblock: Outdated power grids and lack of charging stations hinder EV adoption

Power grid updates will be necessary to keep up with electricity demand as EV adoption rises. Planned capacity increases may generate enough power to handle the coming EV wave. Still, local legs of the grid, used for home charging, face potential bottlenecks without expensive upgrades to power distribution systems.

An increase in EV adoption, particularly in commercial trucking, could strain current power grids, says Jeff St. John, director of news and special projects with Canary Media, a clean-energy news publisher. “It’s just not a load that utilities are used to planning for. On the home-charging side, this can also be a problem.”

Homeowners might need to replace their electrical panels to support EV charging, which costs $2,000–$4,000, according to the electrification nonprofit Rewiring America. Costs are even higher, ranging $5,000–$25,000, if the home requires a service upgrade or transformer replacement — and coordinating with utility companies can cause months-long delays.

The ability to access low-cost home charging is the most significant economic factor in EV adoption. More than 45% of EV owners indicated it was a “critical” or “very influential” factor in their purchasing decisions, according to a 2023 Plug In America survey. But the U.S. will need more public charging stations, too.

“The most recurrent issues flagged by EVhype users include the scarcity of high-speed DCFC stations in certain regions and intermittent reliability across charging networks,” says Rob Dillan, founder of EVhype. The platform’s users, who can review charging stations on the site’s map, want a more seamless charging experience and better station maintenance.

Energy sources should also be greener to foster EV adoption. Environmental protection was the top reason EV owners purchased their electric cars, with more than 40% of respondents in the Plug In America survey indicating it was an important consideration.

Solution: Infrastructure investments create a clean, reliable charging network

The U.S. needs about 28 million ports by 2030 to meet the demand for electric passenger vehicles, according to the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility (MCFM). Private ports will increase the number from about 2.5 million ports to nearly 27 million, MCFM predicts.

Creating a reliable charging network will require significant investment from the private and public sectors, but government support could play a major role in building it quickly enough, says Gillingham.

More funding from programs like the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program, which distributed $885 million across all U.S. states to install alternative-fuel corridors along major highways in 2024, would help build out the infrastructure.

Insurify

Location, location, location

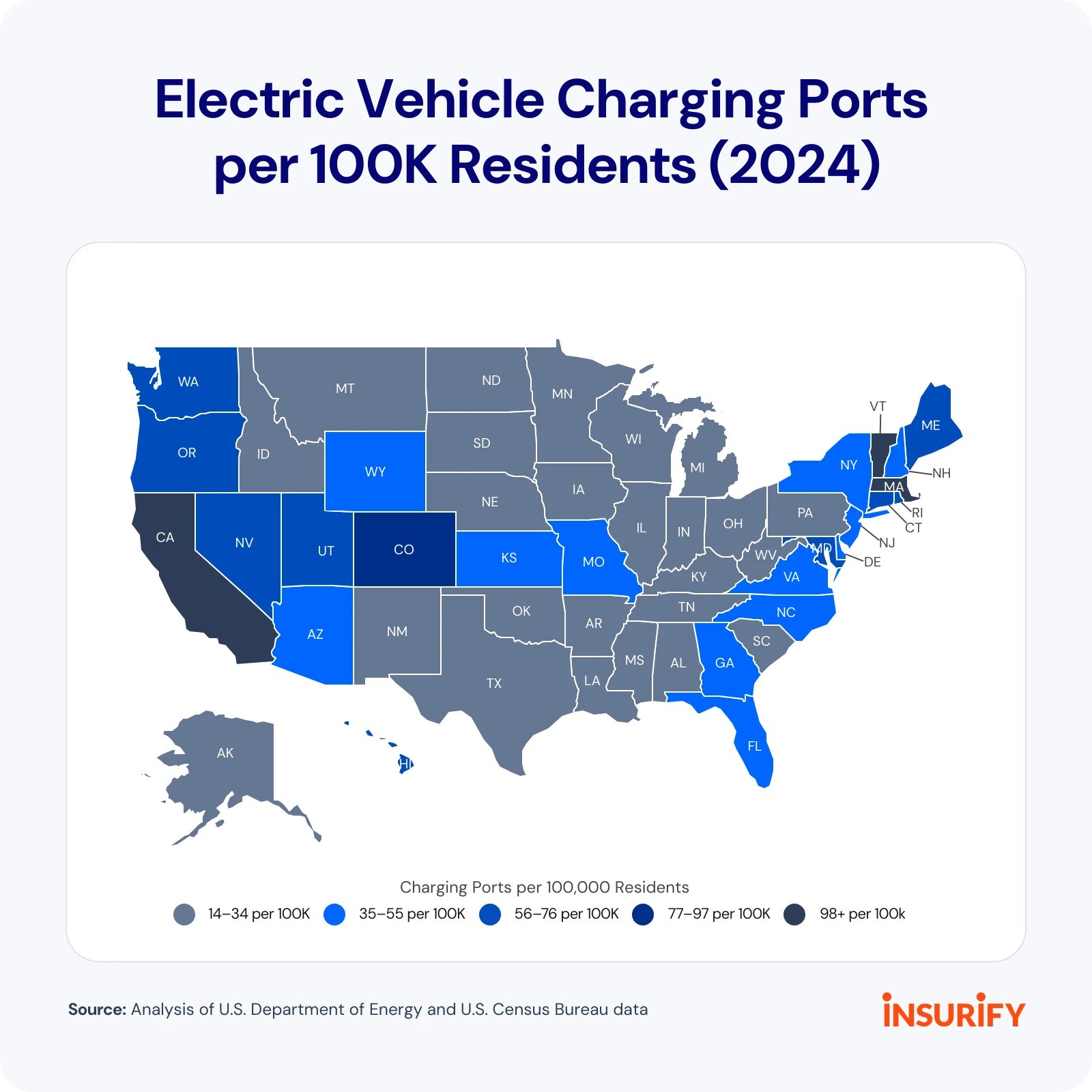

Heatmap showing each state and their “EV Charging Ports per 100K Residents” results in 2024.

The location of charging ports is also important, notes Dillan.

“Many Americans reside in condominiums and apartments lacking adequate charging facilities. Consequently, experts recommend that the U.S. government implement state policies promoting fair access to charging, ensuring underserved areas also benefit from EV charging stations.”

Majority-white tracts are 1.4 times more likely to have charging stations than majority-non-white tracts, Axios reported. Areas with chargers are also 1.14 times as wealthy as those without them.

Public funding could close charging access gaps. The NEVI Formula Program aims to address disparities in charger access, directing the Secretary of Transportation and the Secretary of Energy to strategically deploy infrastructure in rural, underserved, or disadvantaged communities.

The current demand for EV chargers is still so low that it’s difficult to profit, the MCFM concluded. Subsidies and credits — like the 30% tax credit for EV charging stations in low-income or non-urban census tracts under the IRA — can help early investors achieve near-term profitability.

The IRA also designated nearly $3 billion for transmission networks. The Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) Program provides an additional $3.5 billion in investments to strengthen grid resilience across 44 states.

Roadblock: Partisanship and automaker resistance slows EV adoption

The U.S. is becoming increasingly divided on EVs. States with more incentives and infrastructure investments, like California, Washington, Hawaii, and Oregon, have seen steady growth in the EV market share. The states with the lowest adoption, including Michigan, Iowa, Kansas, and Arkansas, saw rates decline in early 2023, according to J.D. Power.

More and more, the divide is happening along party lines. Among the 10 states with the highest EV adoption rates, only Utah voted Republican in the 2020 presidential election. The inverse is true among the 10 states with the lowest EV adoption rates, with only Michigan voting Democrat.

Interest in EV adoption hasn’t always been so partisan. A 2019 Climate Nexus poll showed more than 8 in 10 Democrats and 7 in 10 Republicans viewed EVs positively.

More recent polling from Pew Research tells a different story, with 73% of Republicans saying they would be upset if the U.S. stopped manufacturing gas-powered vehicles compared to just 20% of Democrats.

EV policy is inextricably tied to climate change policy. “Global warming and the environment” ranks as one of the political topics with the most significant increase in polarization over the last decade, according to Gallup.

Republican lawmakers have strongly opposed efforts to electrify the passenger vehicle market, calling the EPA’s 2023 emissions proposal a “de-facto EV mandate.”

Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.), who criticized the Biden administration’s EV objectives as “unrealistic,” argued that EV adoption should occur organically without government regulations imposing it on consumers. Massie, an MIT engineering graduate who lives off the grid on solar panels and drives a Tesla Model S, brought up a valid issue: “The grid’s not ready yet.”

Former President Donald Trump has also been critical on the 2024 campaign trail, saying the Biden administration’s EV policies would cause a “bloodbath,” referring to potential job losses in the auto industry.

Auto manufacturers also opposed the initial EPA rule. Stellantis said the EPA was “overly optimistic” about EV market growth. Toyota said the proposal underestimated key challenges and ignored inadequate battery production infrastructure.

Opposition from car manufacturers isn’t new. In 1970, automakers lobbied against strict emissions standards set by the Clean Air Act, insisting it was technologically impossible to build cars that could achieve targets by 1975. Notably, it was Republican former President Nixon who signed the landmark environmental act into law.

Solution: Addressing barriers cultivates a pro-EV sentiment

Addressing legitimate concerns across the aisle could help EV advocates reach skeptics — and past negotiations and compromises have worked.

The United Auto Workers (UAW) union originally opposed the new EPA emission standards, criticizing the use of taxpayer money to subsidize EV and battery factories without requiring competitive wages.

The Biden administration revised proposed EPA standards to delay the timeline for compliance and allow automakers to meet standards with plug-in hybrid vehicle sales in addition to EVs. The changes reduced job-loss fears and ultimately earned President Joe Biden a UAW endorsement.

Shortly after Nixon signed the Clean Air Act of 1970, Honda engineered an engine that could meet the standards and licensed the technology to other automakers. But manufacturers also won delays, giving them more time to implement the standards. After the EPA softened its 2023 proposal, Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis got on board, if somewhat tentatively.

Bipartisanship and a balance between addressing economic and environmental concerns are key to moving EV adoption toward 100%, even if it’s at a slower pace.

Reaching 100% EV adoption in the U.S.

After compromises with auto industry stakeholders, a projected 56% of light-duty vehicle sales will be BEVs by 2032. Plug-in hybrids, partially electric cars, and efficient ICEs will account for 13% of sales.

Reaching 100% EV adoption will take more time in some states than others. Seventeen states have adopted all or part of California’s low-emission vehicle (LEV) and zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) regulations.

Thirteen states and Washington, D.C., have implemented the more stringent Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) regulations. California and New Jersey plan to have 100% EV sales by 2035. Delaware also adopted ACC II but capped the requirement to 82% by 2032.

Projections on when the U.S. could reach 100% EV adoption vary, but Biden’s original goal of reaching 50% EV sales by 2030 is realistic, Gillingham believes. “There is a lot of time between now and 2050. Many forecasts are much more optimistic about EVs — they see half of new vehicles being EVs by 2030 or 2035. That would be a much faster change.”

By 2030, EV sales will grow by four times, reaching 49% BEV sales by 2030 and 68% by 2035, according to the Boston Consulting Group.

Gillingham thinks the U.S. could see something close to 100% EV adoption, but “not for a very long time.” He also believes some gas-powered cars will hang around, but they might become an exotic niche.

The benefits of total EV adoption are wide-ranging. The U.S. uses more than 66% of its petroleum for transportation, according to the Energy Information Administration, and an all-EV future would lower dependency on fossil fuels.

Reaching 100% EV sales by 2050 would prevent 2.2 million asthma attacks, 10.7 million lost workdays, and 89,300 premature deaths, according to an American Lung Association study.

But the complex and changing barriers to EV adoption make future demand difficult to predict. A sudden increase in gas prices could drive EV demand, as high fuel costs did in 2022. Studies show EVs will drive electricity costs down in the long term, but a short-term price surge could stymie demand. Expiring tax incentives could slow EV adoption, but more rebates could boost it.

St. John prefers not to guess whether 100% EV adoption is achievable. “I try to think more about what needs to happen next, and what needs to happen after that, and after that, and after that — because if talking about all or nothing, people get into terrible and insoluble arguments based on different assumptions they have about what happened in between.”

Methodology

Insurify’s data science team examined more than 97 million rates from car insurance applications in its proprietary database to calculate average insurance rates. Insurify applications come from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Insurify’s comparison platform provides real-time quotes via integrations with insurance companies.

Insurance costs represent the average for a driver between the ages of 20 and 70 with a clean driving record and average or better credit. EV insurance costs are based on 18 bestselling electric car models with the most Insurify applications, representing nine manufacturers.

This story was produced by Insurify and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.