COVID-19 restrictions did little to stop border drug trafficking

This story by Rocío Gallegos, Verónica Martínez, Gabriela Minjares was first published by La Verdad.

Land crossing restrictions imposed by the United States on its border with Mexico by COVID-19 disrupted the dynamics of students, tourists, buyers, formal and informal workers, and thousands of businesses. But it did not stop drug trafficking between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso.

Organized crime groups adapted to new circumstances and overcame the closure that caused a temporary decrease in cross-border drug shipments and the accumulation on drugs on the Mexican side of the border. They diversified their operation patterns.

They achieved their goal of crossing drugs by replacing their Mexican “mules” with American ones, and increased traffic through unpopulated areas between Anapra and San Jerónimo, as well as through the Juarez Valley, where there are no bridges and little surveillance.

They also resorted to a new figure that emerged in mid-2020 within organized crime: “the broker-dealer,” a person outside the structure of a cartel, who traffics drugs independently for different groups and obtains a percentage of the profits.

The entry of drugs into the United States slowed down at the beginning of the pandemic, but the criminal groups made some adjustments to modify their operations, said Kyle Williamson, the Drug Enforcement Administration’s special agent in charge of the El Paso sector.

"We know that the cartels continue to hone their capabilities," he said.

Jorge Nava, prosecutor of the Northern Zone District of the Chihuahua Prosecutor's Office, agreed. He said pandemic restrictions in effect since March 21, 2020, "does little to stop” drug traffickers.

During the first months of the pandemic, traffickers increased retail sales of drugs on the Mexican side of the border, Nava said.

This situation represented a challenge for authorities, who were sure it led to an increase in addictions, drug dealing and homicides on the streets of Ciudad Juárez.

The drug market in El Paso was not affected much as border crossings were restricted. The primary impact on the northern side of the border was the flow of money, which caused large amounts to remain in the United States, according to the DEA.

As organized crime overcame the obstacles of limited cross-border movements, drug users on both sides of the border faced challenges of confinement and economic and emotional difficulties. This unleashed a perfect storm that led many to relapse, according to people who care for addicts.

Impact of restrictions in Ciudad Juárez

The ravages caused by the restrictions imposed on the border were felt almost immediately in Ciudad Juárez, one of the main routes for drug trafficking.

The Chihuahua State Attorney General's Office (FGE) said the city became a warehouse for all kinds of substances that throughout the last year have been dispersed in the streets using new methods, which triggered violence.

"Much of the drug has stayed here in the border cities, which results in a greater number of addicts, especially young people, because the drug continues to be sold. If it is not in the United States, it is here," prosecutor Nava said.

The Chihuahua prosecutor's office said drugs are no longer sold at retail in fixed places, as was previously the case, but have now spread to the streets and are now home delivered when users place orders via telephone.

The DEA is concerned about this new trend of drug distribution on the streets of Ciudad Juárez, because it could provide a comeback of violence that began just over a decade ago.

“We have never seen this before and we are very concerned that this micro-level distribution in Juárez could bring us back to a situation like 2010 or 2009,” Williamson of the DEA said.

Drug distribution changes in Ciudad Juárez also led to changes in consumption patterns.

María Elena Ramos Rodríguez, director of the Compañeros Program, said a kind of geographical line once defined what types of drugs were consumed in the city. But that has changed in the midst of the pandemic.

“Now we see that this line is less and less fixed, and that in sectors like downtown, in old neighborhoods of Juárez, crystal meth is now also being consumed. And in sectors of the new Juárez, where crystal meth was being consumed, now heroin is also being consumed,” she said.

Compañeros treated some 7,000 people with addiction issues last year.

How drug smugglers adapted to pandemic restrictions

Prosecutor Nava said that although cross-border drug trafficking was interrupted for about two and a half months after the restrictions, it was soon reactivated with new methods and routes to achieve the smuggling task "at any cost".

He said organized crime structures now seek U.S. citizens to smuggle drugs into the United States, since they do not have mobility restrictions at border crossings.

"This is one of the main phenomena that the closing of the bridges left us, that now there are more people of North American nationality involved in this criminal dynamic to smuggle drugs into the United States," he said.

This pattern is reflected in the statistics of people detained in Ciudad Juárez after being accused of drug dealing.

State prosecutors in Chihuahua reported a 55% increase of Americans arrested for drug crimes in 2020 compared to the prior year.

The Special Unit for Drug Crimes reported that 68 people born in the United States were arrested on drug crimes, 24 more than in 2019.

Nava said they have also found cases of Americans who come to Ciudad Juárez to buy drugs for their personal consumption and seek to cross the border with it.

Another new factor discovered by Chihuahua prosecutors is the emergence of “broker-dealers in the drug-trafficking chain. They work independently and are not part of any criminal group, Nava said.

"What is their function? Receive a shipment of drugs from a certain criminal group and take it under their responsibility to a certain city in the United States. In some cases, they are American citizens, but they are people who are already dedicated to this activity,” he details.

He said they began seeing broker-dealers in mid-2020, as Chihuahua officials arrested Americans with considerable amounts of drugs, mainly synthetic drugs such as fentanyl and crystal meth.

“What these people tell us is: 'I don't work for any group, my role is as a broker-dealer.' Well, explain to me what it is to be a broker-dealer? 'I get paid by people from a criminal group or people who traffic drugs independently, so that I can take it to the United States. That's why they pay me a percentage of what I smuggle, but I can smuggle drugs for the Jalisco cartel, the Sinaloa cartel, the Juárez cartel.’ This is also a new variety of drug trafficking,” Nava said.

Prosecutors have also seen greater drug trafficking in the sectors of Anapra towards San Jerónimo and the Juárez Valley, which are areas that have become conflict zones because they are also used by organized crime for human trafficking.

One year after the closure of the border, prosecutor Nava said drug trafficking from Mexico to the United States remains intact.

Drug flow into U.S. increases

The U.S. DEA agrees with that assessment. In its annual report, the agency reports that the operations of transnational drug criminal organizations were not significantly impacted by the border restrictions implemented in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

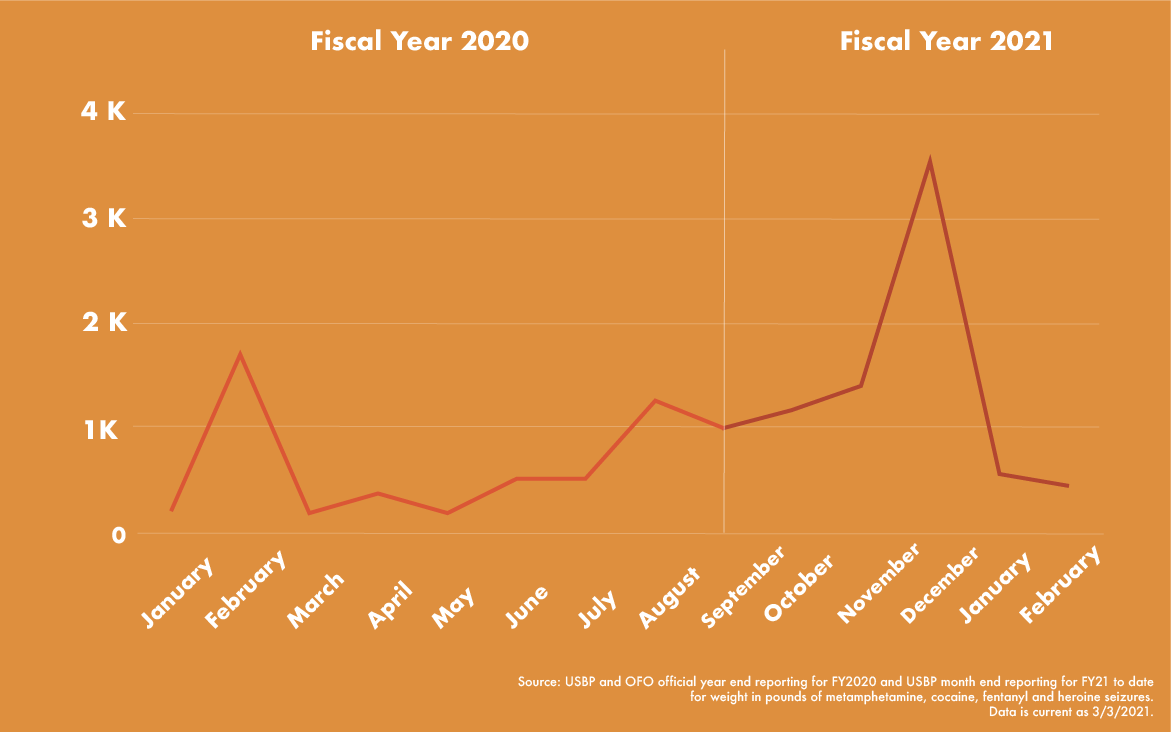

The closure of international crossings had an impact on drug importation from México only in March, April and May, Williamson said. This trend was also seen by other U.S. agencies, including Customs and Border Protection.

In February 2020, CBP seized 5,607 pounds of controlled substances at the ports of entry between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. With mobility restrictions, drug confiscation plummeted by March almost 50 percent, to 2,596 pounds.

The decrease continued in April and in May CBP officers seized 1,473 pounds of drugs at regional ports of entry.

By June the outlook was different.

"Now, all law enforcement agencies on the border, we are seeing a significant increase (in drug trafficking) and we are already exceeding the totals (of seizures) for fiscal years 2019 and 2020. That is not normal," Williamson said.

So far in fiscal year 2021 -- from October to February -- CBP reported seizing a total of 7,108 pounds of marijuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin and fentanyl on the border between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez.

This figure is almost equivalent to the seizures of the entire 2020 fiscal year, when 7,176 pounds were seized. In 2019, total seizures amounted to 3,617 pounds.

So far in the 2021 fiscal year, fentanyl is the drug with the highest growth in seizures between Juárez and El Paso, followed by cocaine, heroin and methamphetamines, according to CBP reports.

U.S. authorities also report that land restrictions at the border made it difficult to smuggle money into México. Consequently, large amounts of money remain in the southern United States awaiting their transfer to Mexican territory.

Pandemic stresses fuel drug use increases

The coronavirus restrictions created conditions that triggered increases in drug use and addictions on both sides of the border.

The demand for drugs grew due to the anxiety from the loss of employment, the physical and mental effects of the confinement and the mandatory social distancing due to the pandemic.

"The stress of being in confinement or of the contagion risk makes us fall into a situation of constant stress and that can become a trigger factor for substance use," said Lizeth Gutiérrez, coordinator of the Chihuahua State Commission for Attention to Addictions (CEAADIC) in the North Zone.

This was reflected with an increase in the number of people that addiction care groups reported in the last year, such as the Compañeros Program, which registered an increase of 20 percent of people seeking its services.

According to a survey on drug use carried out by the Trust for Competitiveness and Citizen Security (FICOSEC) as of 2019, about 53,000 people in Ciudad Juárez were frequent users.

Prosecutor Nava estimates that 30 percent of people with addiction do not appear in arrest or investigation records and have not been part of a rehabilitation process.

El Paso also reported an increase in addictions, particularly for people who relapsed in the middle of the COVID crisis.

"The pandemic did affect people who were recovering from drug or alcohol addiction, because stress, unemployment and the crisis we are facing aggravate the situation and many relapse again," says Guillermo Valenzuela, operational director for Aliviane, a non-profit organization in El Paso offering addiction prevention and rehabilitation services.

Pandemic restrictions situation unleashed a crisis on both sides of the border for drug users, who faced challenges finding medical services and support centers.

Some centers closed, others limited their capacity, others transferred their therapies to digital platforms that some people with addictions could not access, and some required a COVID test to provide the service.

In Ciudad Juárez, addiction care facilities reported a decrease in patients treated, going from 5,700 in 2019 to 5,400 last year.

In El Paso, Michael Jiménez, director of the downtown Victoria Center, said COVID also made it more difficult to help people with addictions. “Now they have to take a test, and between the moment they decide to ask for help and the moment they get the test, many people do not return. Now, instead of receiving them directly, we have to refer them to another place to be reviewed.”

Mexican authorities say drug trafficking, drug dealing and addictions are factors causing violence. Ciudad Juárez reported 1,646 murders in 2020.This story was produced as part of the Puente News Collaborative, a binational partnership of news organizations in Ciudad Juárez and El Paso.

This story was produced as part of the Puente News Collaborative, a binational partnership of news organizations in Ciudad Juárez and El Paso.