Juárez native escapes war in Ukraine: ‘I was ready to give my life for my family’

Juárez native escapes war in Ukraine: ‘I was ready to give my life for my family’

At a Juárez café, half a world away from the freezing temperatures and falling bombs he fled just 10 days ago, Javier Donlucas roughly cleared his throat as he scrolled through the videos and photos he captured during his escape from Ukraine.

“Here’s one where I think you can hear the bombs,” he said in Spanish as he tapped play. A gray street in Kyiv appeared on the screen, bouncing up and down in rhythm with Donlucas’ steps, the whine of air raid sirens providing a soundtrack.

Donlucas, a Mexican citizen who lived in Ukraine for the last four years, arrived in Mexico City with his Ukrainian wife, Lesia, and their three-year-old son, Sasha, earlier this month. He’s now back in his hometown, Ciudad Juárez.

But the knowledge that his wife’s family, along with millions of other innocent people, are still in danger keeps Ukraine and the war fresh in his mind.

As Donlucas tells it, he ended up living in Ukraine accidentally. After he graduated from the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez with a degree in music, he made several world tours with Mexican ballet and cultural groups, meeting Lesia, a Ukrainian ballerina, in Poland. They were living in Mexico when they decided to visit Ukraine for what was supposed to be a brief trip.

While there, they discovered that they were going to be parents, but a complication with the pregnancy meant Lesia could not travel back to Mexico. They stayed in the city of Lviv, near the Ukraine-Poland border, where Donlucas began to learn Ukrainian and pick up gigs and odd jobs. He also wrote and published a book on teaching music to special needs children, which helped launch his career as director of the Chopin Music and Art School, an academy that focuses on special needs students.

When Russia began its invasion of Ukraine in late February, Donlucas and his family lost the life they had created in a matter of days.

“About two months before the war started, when I found out (the Russians) were approaching the border as they do every year for so-called ‘training exercises,’ I knew something was wrong,” Donlucas said as he sat outside a coffee shop near the Rio Grande mall. “There were so many of them. So I called the (Mexican) embassy to request documents for my son.”

The family left Lviv, about 370 miles east of the Ukrainian capital, on a night train on Feb. 23 and arrived in Kyiv early the next morning for their appointment at the Mexican embassy. By then, Russian forces had begun to bomb the city.

“As we got off the train, we could hear the bombs, and feel them,” Donlucas said. “I was very afraid.”

The embassy wasn’t scheduled to open for a few more hours, but Donlucas managed to contact an embassy employee soon after they disembarked from the train. The employee, unable to find transportation, arrived by foot an hour later and processed a birth certificate and Mexican passport for Sasha.

As the family waited at the train station to return to Lviv, air raid sirens sounded. Within seconds, everyone ran to the nearby underground subway station to escape the Russian shelling.

“I ran with my son in my arms and my wife was carrying our backpack,” Donlucas recalled. “We were going down an escalator and people were sliding down the handrail to the bottom. The woman on the speakers was crying and screaming, ‘They are bombing us, please take refuge.’”

The electricity in the station was suddenly cut off and panic ensued. Crushed in the flow of people, Donlucas shouted for the crowd to keep making their way down to the lowest level.

He and his family boarded a subway car and rode it for just one stop, getting off to seek shelter in a cultural arts center where Lesia had once worked, which now served as a bunker.

“We could hear the sirens, and I carried my son for 2 kilometers along with the suitcases, and the bombs falling on either side,” Donlucas said. “It was very difficult because one wrong step and any one of us could lose our life. I would have wanted it to be mine so that my son and my family could escape.”

In the bunker, they weighed their options for escape, deciding to try once more to catch a train back to Lviv. The station was packed, and in the panic to board the train, the crowd began to push forward. Sasha cried out.

“They started to crush him, and he began to scream and cry from fear,” Donlucas said. “When people saw that my child was being crushed, they began to open a space.”

As he climbed aboard, his son in his arms, Donlucas turned, expecting to see Lesia behind him.

“I looked to the door and she was there screaming among the crowd,” he said. “I don’t know how I did it, but I grabbed the train with one hand and I reached out and grabbed her with the other. They were all pulling her by the backpack to keep her from boarding. I lifted her with all of my strength and we left all the bags behind and we saved ourselves.”

The trip westward to Lviv, which would normally take 6 to 8 hours, lasted more than 20 hours. Passengers were instructed to turn off location services on their phones so Russian forces couldn’t pinpoint the train’s whereabouts.

“When we were approaching each city, the train would turn off and stop. We had to be quiet. We had to keep the curtains closed,” Donlucas said. “And the bombs would start, ‘boom, boom,’ on either side. And we would move forward very slowly, and again, ‘boom, boom,’ and (the train) would turn off again. (The Russians) were bombing the trains and the tracks.”

As soon as they arrived in Lviv, Donlucas was already thinking about the next leg of their escape. Though only about 50 miles from the Polish border, friends had warned that the wait time to cross by foot was at least six days, and even longer by car, so Donlucas hired a driver with a van to take them south to Chișinău, Moldova.

Realizing that any Ukrainian money he still had would soon be worthless, Donlucas paid the driver to take three strangers along with them.

From Moldova, they took a bus to Bucharest, Romania, where an airplane sent by Mexico’s government would be waiting for them and dozens of Mexican, Ecuadorian and Peruvian citizens who were also fleeing Ukraine.

According to Mexico’s secretary of foreign affairs, that flight landed in Mexico City in the early hours of March 4, more than a week after the family first set out from their home for Sasha’s passport.

Even while still on the road to safety, Donlucas’ thoughts were on the colleagues and students he was leaving behind. When a teacher at his school called to ask how to handle an upcoming rental payment, he did not hesitate -- he sent the money and gave everything left in his bank account to his colleague. She used the money to buy food and supplies, and opened the school as a shelter for students and their families.

“That was the least we could do since we were already leaving,” Donlucas said.

Donlucas feels lucky that his family is together. Other mixed-nationality and Ukrainian families were separated because adult male Ukrainians had been ordered to remain in their country.

“I would see the women talking to their husbands who were going to combat,” he said. “They would be saying, ‘We are fine,’ but in reality, when you see their faces, they are not happy faces.”

He blamed Russian military tactics for mounting civilian casualties, accusing Russian forces of deliberately targeting humanitarian corridors and hospitals.

“They are killing human beings that are not at fault, like children. I worked with children,” Donlucas said. “I wanted to give them an education, and they are taking away their lives.

“I want the soldiers to think about how much a life is worth or how much (their) mental integrity is worth, seeing as how (they are) killing children and innocent people.”

Although he and his immediate family are in Juárez, safe from Russian air strikes, Donlucas blinked away tears while he scrolled through photos of his family’s final days in Ukraine. At moments, their ordeal does not quite seem real, but he worries about the long-term effects on his son, he said.

“It might seem like I am inventing a dramatic story, but it was real,” he said. “We are alive and we are happy. But there are many people who are not happy. And that unhappiness, or sadness, or rage, that courage that helped us get out, I felt all that. To get your family out, you can do anything, even give your life. And I was ready to give my life for my family.”

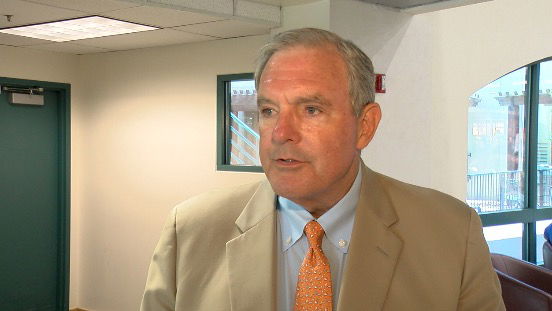

Cover photo: Javier Donlucas, pictured in his native Juárez on Sunday afternoon, earned a degree in music at UACJ and then opened a music school for special needs children in Lviv, Ukraine. He escaped from the Russian invasion with his Ukranian wife and son on March 3. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()