The origins of 20 political words and terms

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Ciano // Stacker // Shutterstock

The origins of 20 political words and terms

Collage with hands holding megaphone and showing political placards.

“Gerrymander,” “blue states,” and “red tape.” These words populate headlines and newspaper articles regularly, with many writers taking their meaning for granted, but a look through history can reveal surprising changes in meaning over time.

In a political landscape challenged by personal interpretation, etymology can be a reliable narrator. Tracing a word’s emergence and exploring the circumstances behind any changes in meaning offers a window into the surrounding historical context, offering insights into how it shaped today’s broader discourse. Moreover, for etymology buffs who have found their interests captured, understanding the paths words have taken can encourage participation and engagement with matters of public policy.

Some phrases emerged from, sparked, or shaped significant social movements, such as the term “identity politics,” which was born of the Combahee River Collective. Some storied origins of terms, such as “faithless elector,” reveal the convoluted ways of politics. Meanwhile, words such as “woke” have been demonstrably co-opted for reasons that oppose their founding purpose. Some turns of phrase have long histories; others, like “founding fathers,” are surprisingly recent; and who knew “red tape” went as far back as the Holy Roman Empire?

Despite the differences in the terms’ purposes and origins, each phrase has served a vital role in shaping the political world. In light of the ongoing political dramas that unfold globally each day, Stacker traced the origins of 20 words and terms used in political discourse using historical archives, research reports, and news articles.

![]()

Federal Communications Commission/PhotoQuest/Getty Images

Founding fathers

Warren G Harding speaks into microphones at a campaign stop.

While the term “founding fathers” may seem to predate American politics, it was only invoked for the first time in 1916 by then-Sen. Warren G. Harding during the Republican National Convention of the same year. He repeated the phrase many times throughout his political career, sealing it into the greater lexicon.

The term remains largely undefined. For example, one proposed criterion implies those who signed the Declaration of Independence, which leaves out George Washington and James Madison. Meanwhile, John Adams himself rejected the designation outright, writing that the titles “founder” and “father” “belong to no man, but to the American people in general.”

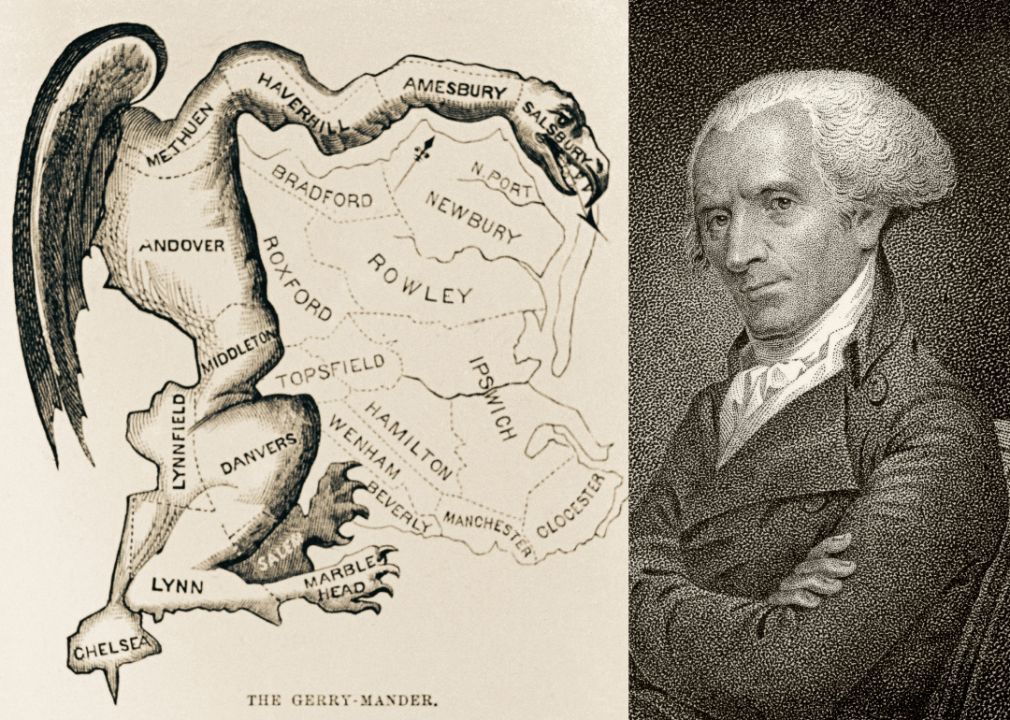

Universal History Archive // Getty Images; Bettmann // Getty Images

Gerrymander

Engraving of Elbridge Gerry with a Gilbert Stuart political cartoon of a Massachusetts electoral district.

A “gerrymander” happens when redistricting a voting area favors a political party. Its origins came from Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who was a framer—but not a signer—of the Constitution. He also argued against electing congress members to the House of Representatives directly.

When Jeffersonian Republicans presented him with a redrawn map for a Massachusetts district in 1812, which encompassed more of their supporters, he signed the bill supposedly with reluctance. During a dinner party held by opposing party members, illustrator Elkanah Tisdale added monster features to the district map. At the same time, poet Richard Alsop jokingly named his creation a “Gerry-mander.” Today, the practice continues to produce amorphous districts—such as Pennsylvania’s former Seventh Congressional District, nicknamed “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck.”

vectorfusionart // Shutterstock

Fair-fight district

Republican elephant and Democratic donkey on top of American flag and vote stickers.

A “fair-fight district” results when redistricting results in a voting area that favors no political party. When the New York legislature reapportioned the state’s districts in 1982, it left the 22nd district with two incumbents approaching their election year: one Democrat and one Republican. The district comprised rural farmlands encompassing parts of the Bronx, leading commentators to name the electorate in dispute as a “fair-fight district,” printed in The New York Times for the first time on Nov. 1, 1982. Democrat Representative Peter A. Peyser ended up losing his seat to Republican Representative Benjamin Arthur Gilman.

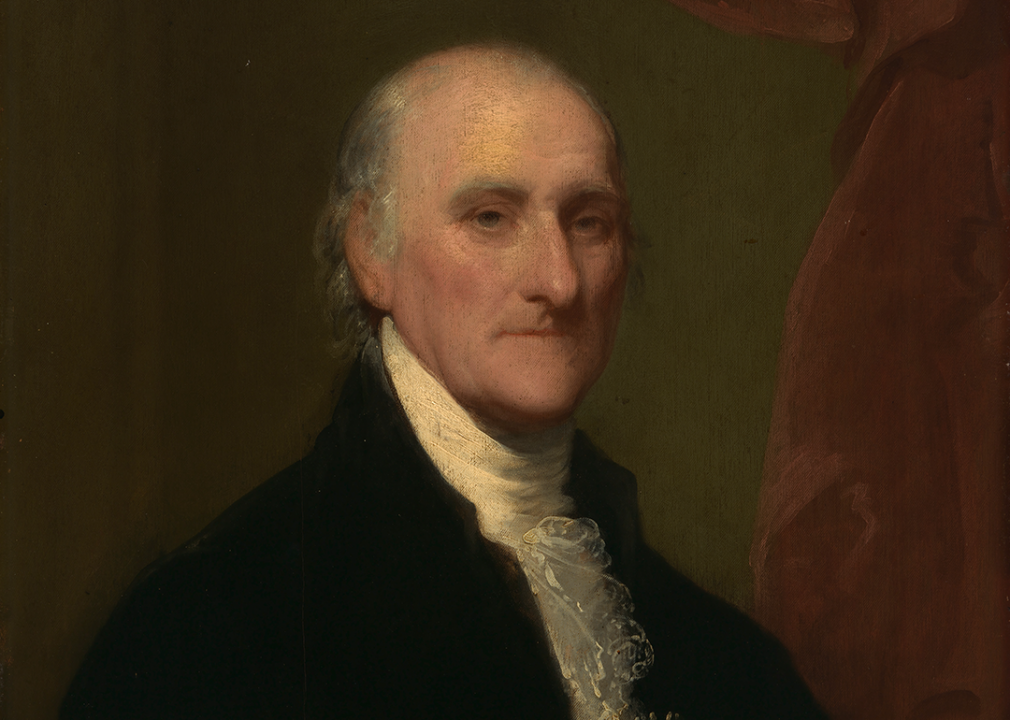

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Faithless elector

Gilbert Stuart portrait of Samuel Miles.

A “faithless elector” is someone in the Electoral College who votes against their party’s nominee.

The first faithless elector, Samuel Miles, cast his 1796 presidential election vote for Thomas Jefferson against the will of his John Adams-supporting constituency. One of his constituents aired his grievances to the American Gazette in a letter to the editor: “Do I chuse Samuel Miles to determine for me whether John Adams or Thomas Jefferson shall be President? No! I chuse him to act, not to think!”

As of 2020, 23,507 electoral votes have been cast in American presidential elections, 90 of which were cast in opposition to the populace. Of those, 63 were cast for the other nominee due to the death of their opponent. In July 2020, the United States Supreme Court held in Chiafalo v. Washington that states are permitted to “penalize an elector for breaking his pledge and voting for someone other than the presidential candidate who won his State’s popular vote.”

Barbara Alper // Getty Images

Identity politics

Florynce Kennedy speaks at a Women’s Day Rally in Boston.

Identity politics typically refers to the efforts of a group to rectify collective injustices suffered due to shared personal attributes, including race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or culture. The concept was born of the Combahee River Collective, established in 1974, which asserted that the ongoing feminist and civil rights movements did not adequately address the concerns of Black women and lesbians. The 1977 statement issued by the group sparked academic and social exploration into the concept of intersectionality as well.

Stefano Bianchetti/Corbis via Getty Images

Red tape

Illustration of Charles V on horse.

Red tape refers to excessive or rigid rules and processes that impede progress and decision-making, and there was a time when it was much more literal.

“Red tape” emerged during the Holy Roman Empire of Spanish King Charles V in the 16th century. His government allegedly used red ribbons to identify important documents, a practice carried out throughout the colonization of America and beyond. According to the National Archives, during the American Civil War, the War Department bought 154 miles of red tape in the fiscal year ending in June 1864.

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Woke

Promotional portrait of Leadbelly Ledbetter singing with guitar.

Woke refers to a state of being that is attentive to social justice and civil rights matters.

While likening awareness of racial injustice to being “awake” predates the 20th century, the phrase “stay woke” was often used in Black communities as a reminder to be on one’s guard, especially when it comes to dealing with law enforcement.

The earliest known use of the phrase began with Lead Belly, a pioneering folk and blues musician. In his 1938 song “Scottsboro Boys,” he recounts the true story of nine Black teenagers who were wrongfully convicted of a crime for which they were sentenced to death. After the song and at the end of the recording, Lead Belly warns: “I advise everybody, be a little careful when they go along through Alabama—best stay woke, keep their eyes open.”

The same term that helped amplify the Civil Rights Movement in America has since been co-opted to censor its history via legislation such as the Floridian “Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” which prohibits some topics on race relations within the state’s education system and workplaces.

Canva

Joe Six-Pack

Close up beer cans.

A derivative—or arguably pejorative—version of John Q. Public, Joe Six-Pack was popularized by author Martin F. Nolan to refer to working-class Americans. In this case, “six-pack” refers to a half-dozen cans or bottles of beer.

In a 1970 article covering a Massachusetts state senator election between Joe Moakley and Louise Day Hicks, he described one of the former’s campaigning strategies as “shouting in Joe Six-Pack’s ear to wake up and face the [unsimplistic] facts of life.”

Rischgitz // Getty Images

Lame duck

English author, Sir Horace Walpole,

In politics, a lame duck typically refers to a politician who loses influence after election defeat until the inauguration of their successor. With less accountability to the public, they tend to either accomplish very little or push unpopular initiatives through at the last minute.

Though it’s a political term today, its use began in finance. The phrase originated around the 18th century, when British nobleman Horace Walpole referred to investors who defaulted on their debts.

“Lame duck” eventually made it across the pond, where it was used to describe temperance supporters who eventually left the movement. It then crossed over to politics and was finally used in a 1926 Grand Rapids Press editorial to describe how the outcome of senate elections could affect Calvin Coolidge’s last years of presidency.

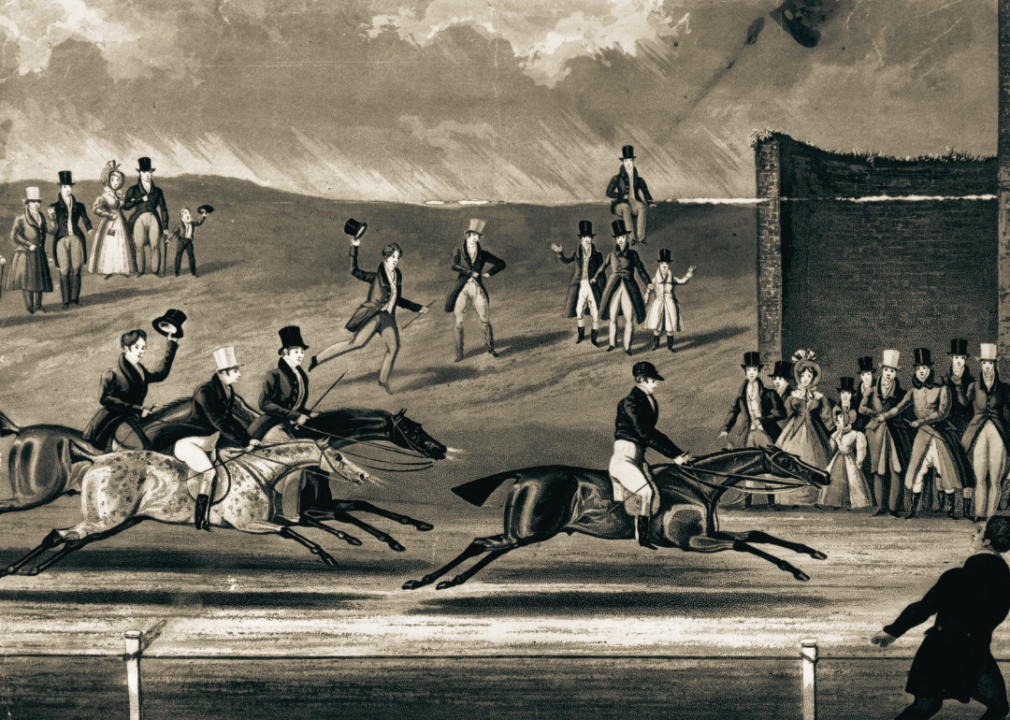

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Dark horse

Illustration showing cheering crowd watching a horse race.

In 19th-century horse racing, “dark horses” were contestants bettors knew very little about since they had been trained in secret or “in the dark.” The goal was to train them so well that it led to a surprise win and a maximized betting payoff. An early use of the term came from British novelist Benjamin Disraeli, who used the term in its horse-racing context for his novel “The Young Duke.”

By the 1840s, the phrase moved to the political realm to refer to an unknown candidate being nominated after multiple rounds. In 1844, Democratic politicians could not agree on a candidate for the upcoming presidential election as they disagreed with Martin van Buren’s opposition to annexing Texas. On the ninth ballot of the Democratic National Convention, they officially nominated “compromise candidate” James K. Polk, who defeated opponent Henry Clay in the election despite being lesser known.

The Print Collector/Heritage Images via Getty Images

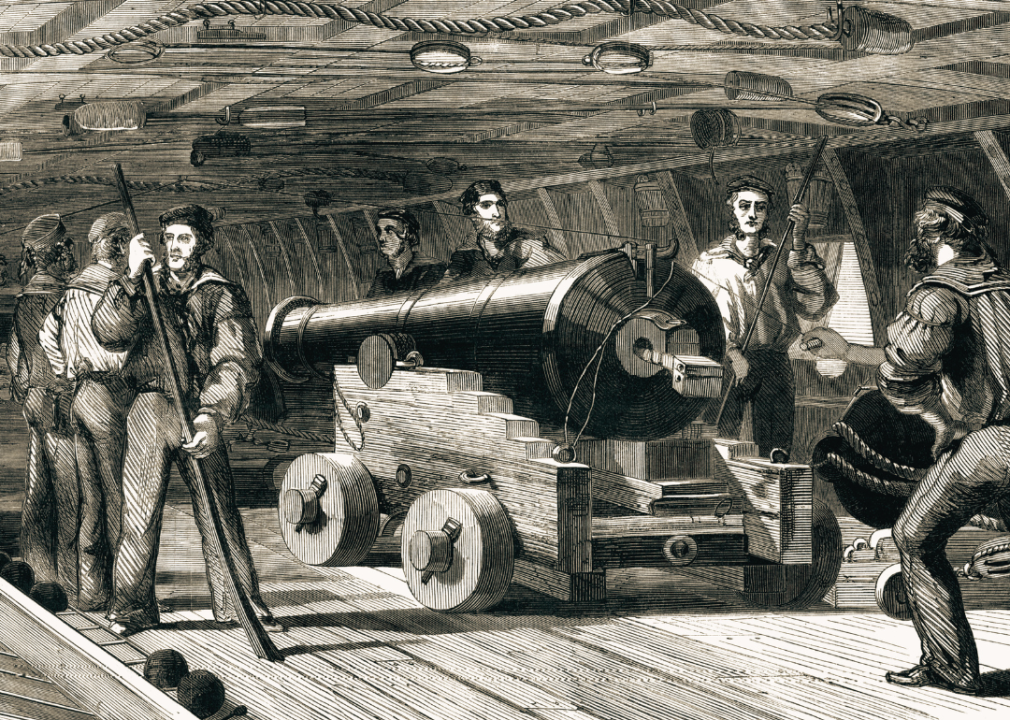

Loose cannon

Illustration showing gun practice on board HMS Brilliant.

Muzzle-loading cannons, once very popular in naval artillery, weighed thousands of pounds, were mounted on wheels, and in the event of strike or turbulence, could break free of restraints and become a “loose cannon.”

Former President Theodore Roosevelt feared becoming a similar hazard given his youth relative to his predecessors and lacking track record upon taking office following 25th President William McKinley’s 1901 assassination. He supposedly expressed his concern to a journalist friend about one day becoming “the old cannon loose on the deck in the storm.”

Canva

Echo chamber

Microphone in a recording studio.

Physical echo chambers date back to the 20th century when recording studios were modified to amplify echoes and reverberations. In a 1955 New York Times article, reporter Elie Abel described the circular, futile discussions between American and Chinese ambassadors as “…an echo chamber for rumors, one often contradicting the other.” This marked the first time the term was used to describe a closed environment in which members are exposed only to the same biased viewpoints they already hold, reinforcing their existing beliefs and developing resistance to outside perspectives.

Truman Moore/Getty Images

Gridlock

Traffic in New York City during a transit strike.

The term gridlock, now often used to describe political stalemate due to a lack of consensus, has quite literal origins. It was first used to describe the type of traffic congestion that emerges due to a road network that is so crowded that no one can move ahead.

The term was printed in a more generalized political context in the Financial Times in 1983 about budget discussions: “The political ‘gridlock’ in Congress might mean that no budget resolution could be passed for fiscal year of 1984.”

Archiv Gerstenberg/ullstein bild via Getty Images

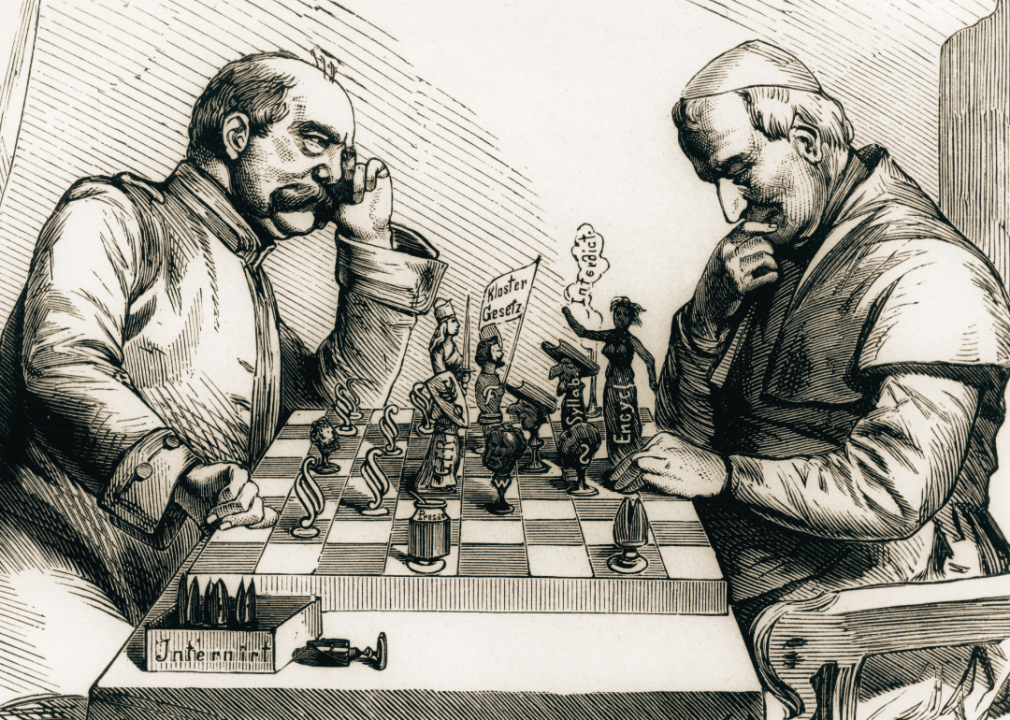

Culture war

Political illustration showing Otto von Bismarck and Pope Pius IX playing chess.

This broadly encompassing term originates in 1871 and derives from the name of the seven-year-long conflict between the Catholic church and the government in Prussia: Kulturkampf. The conflict resulted in attempted assassinations of politicians, arrests of churchgoers, and riots.

University of Virginia sociologist and author James Davison Hunter redefined “culture wars” in his eponymous book “Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America” to describe the polarization of the American electorate based on ideological worldviews.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Silent majority

Portrait of Justice John Marshall Harlan.

The existence of a “silent majority” within a country implies that a majority of the population does not express their political beliefs. The phrase was once meant to refer to those who had already died, such as when Justice John Marshall Harlan used it to refer to Civil War captains who had “long ago passed over to the silent majority, leaving the memory of their splendid courage.”

Former President Richard Nixon secured the term into the political lexicon, albeit with a different meaning, with his “Silent Majority” speech on Nov. 3, 1969, requesting support for the Vietnam War from “the great silent majority of my fellow Americans.”

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Grassroots

Theodore Roosevelt at desk.

Unlike other fundraising or political efforts prioritizing members with the most resources and influence, grassroots movements begin from the local level, or “roots,” working their way upward.

One of the first printed usages of the term appears in a 1904 newspaper. In reference to the strategy of prospective running mate Eli Torrance to incumbent President Theodore Roosevelt, a political organizer is quoted as saying: “Roosevelt and Torrance clubs will be organized in every locality. We will begin at the grass roots.”

Bettmann // Getty Images

Lobbyist

Woodcut by Theo R. Davis showing lobbyists at the reception room at General Grant’s headquarters.

Ulysses S. Grant is widely credited for coining the term “lobbyist” to describe the people who bombarded him with legislative requests while he tried to relax at the Willard Hotel during his 1869-1877 tenure.

However, the term originates in England and references the lobbies in the House of Commons where the public is permitted to congregate and speak with representatives, according to former editor-at-large for the Oxford English Dictionary Jesse Sheidlower.

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

Blue states and red states

Two women mark election results on a board.

In a truly patriotic dispute, the practice of referring to Democratic and Republican strongholds as “blue states” and “red states” begins with fireworks. In 1900, the Chicago Tribune planned to light blue fireworks to signify Republican wins and red to signify Democratic wins on an election night. A competing newspaper announced plans to set off fireworks with the opposite colors in an attempt at sabotage—blue for Democrats and red for Republicans—leading the Tribune to abandon their idea.

The terms took on new life following the mass adoption of color television. Former host of NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Tim Russert, is widely credited with popularizing these two phrases, which would solidify the color-coding of American electoral maps.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Pundit

Illustration of The Reverend W Carey with a Brahmin Pandit.

“Pundit” derives from the Hindi word “pandit,” meaning a learned or skilled person. It entered the English lexicon in the 17th century to describe Indian court officials who served as advisors of Hindu law to English judges.

The modern take on the term applies to many more people. According to Dictionary.com, a “pundit” is simply any person “who makes comments or judgments, especially in an authoritative manner.”

Niyazz // Shutterstock

Dog whistle

Speech podium with two microphones and American flag.

A “dog whistle” is a subtle call to action or statement that is coded or otherwise obscured to appeal to supporters and avoid detection by opponents. Of course, literal dog whistles predate the political usage of the term and refer to manufactured objects that produce a sound only canines can hear. During the civil rights period, it became a broader term to describe secret signals or languages meant to exclude others.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, its figurative form first appeared in an October 1995 edition of The Ottawa Citizen: “On the lips of Premier Mike Harris, the term ‘special interest’ has the tone of epithet. It’s an all-purpose dog whistle that those fed up with feminists, minorities, the undeserving poor hear loud and clear.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.