7 moments of Asian American and Black American solidarity

Photo illustration by Elizabeth Ciano // Stacker // MPI // Getty Images; NARA; Library of Congress

“Divide and conquer” is a maxim that has proven effective in numerous scenarios—such as negotiations and computer programming, for example. But, more insidiously, it has also been used to cement social hierarchies.

Wealthy colonial Americans used the perceived superiority of one race over another to disrupt the solidarity of those in lower income brackets and retain their hold on economic systems. During the early 1900s, labor groups of different ethnicities were often introduced on plantations to prevent strikes and maintain low wages, according to Ronald Takak, a pioneer of ethnic studies.

Fast forward a century to 2020, when the same tactic put Asian Americans and Black Americans on opposing sides of a fabricated struggle. In reality, however, interracial solidarity was the foundation for many freedoms taken for granted today.

Drawing on research from university history departments and local news publications, Stacker compiled a list of seven moments in history where Black and Asian solidarity in America made civil, labor, and economic freedoms possible.

That solidarity has fueled the urgency for those in power to sow dissent, just as it did in 2020. With the death of George Floyd and the prevalence of police brutality against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, videos of anti-Asian violence perpetuated by Black Americans began increasing on social media sites. Given the rise of violence and discrimination against Asian Americans during the pandemic, some called on police and city officials to get tougher on crime, just as protests calling for the opposite were happening.

But those videos didn’t show the bigger picture. Research indicates that the majority of hate crimes against Asian Americans are committed by white people. A study released by the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans found that fringe social media accounts were actively pushing media surrounding Black people committing hate crimes against Asians, spreading fear and division between two underrepresented groups, and manipulating the narrative surrounding hate crime statistics.

Disinformation like that contributes to the “model minority” myth, which paints Asian Americans as successful and contrasts their “progress” to minimize the role of racism in explaining the state of Black Americans, creating a wedge between the two communities. Since 2020, efforts have been made to dismantle this misconception. For example, Renee Tajima-Peña, a filmmaker and professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, teamed up with journalist and cultural critic Jeff Chang to establish the May 19th project, a multimedia endeavor celebrating interracial solidarity.

Programs such as these remind us that there have been moments when Asian and Black Americans found common ground—and society was all the better for it. Here are a few other inspiring moments in history.

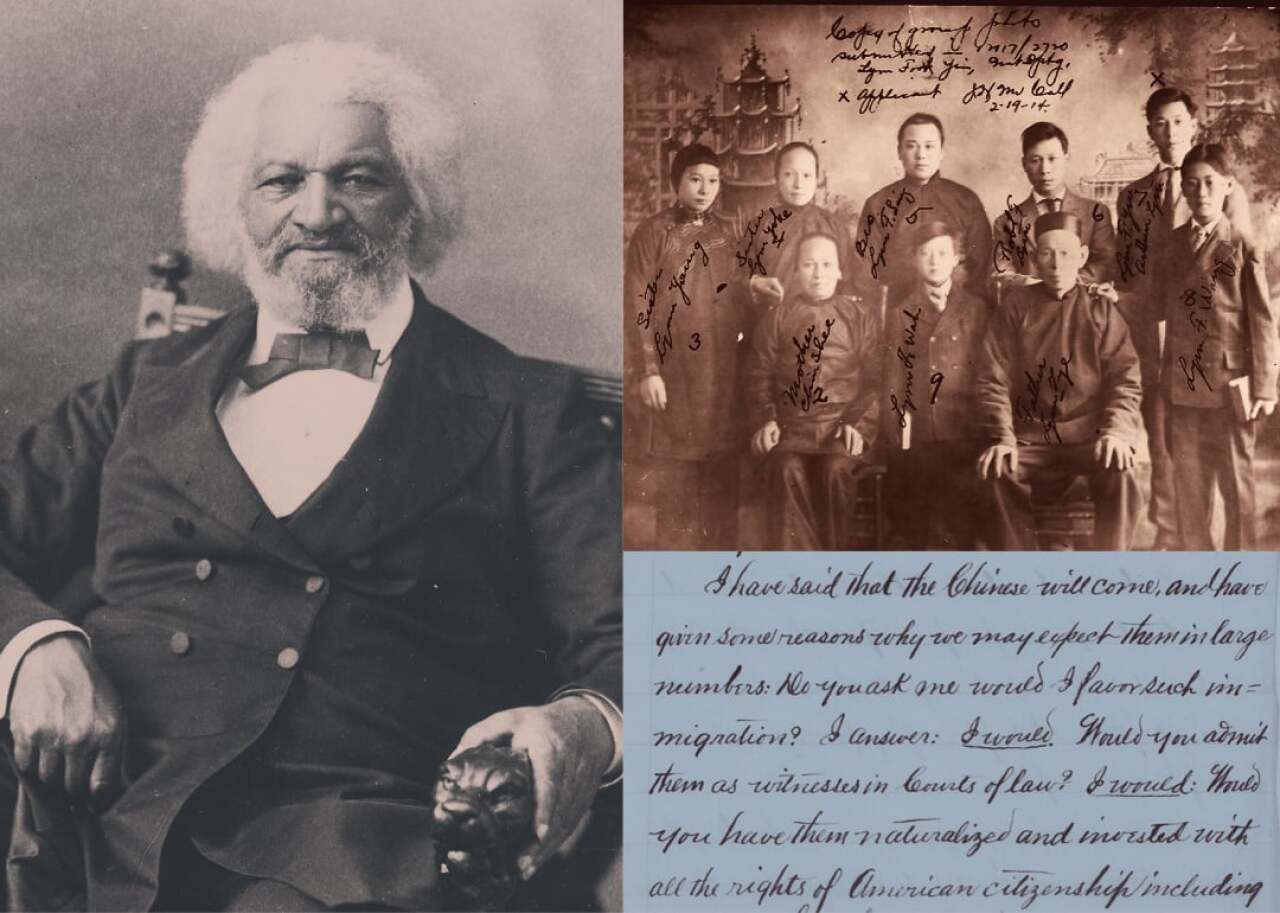

Frederick Douglass opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act

In the 1850s, when Chinese laborers began emigrating to the United States, the federal government passed the first significant act of restricting immigration in the U.S.: the Chinese Exclusion Act.

For more than eight decades, this act (and others that followed it) allowed the U.S. to make it extremely difficult for Asian people to enter the country. It protected the federal government when it indiscriminately and arbitrarily deported people who were already in the U.S.

In 1869, American abolitionist Frederick Douglass argued against the Chinese Exclusion Act in a speech called “Composite Nation.” The speech still rings true today. Back then, white nationalists thought an influx of Asian immigration would “take over” American culture—a consistent talking point by far-right conservatives who want to restrict immigration today.

“The apprehension that we shall be swamped or swallowed up by Mongolian civilization; that the Caucasian race may not be able to hold their own against that vast incoming population, does not seem entitled to much respect,” Douglass wrote in his speech.

Black Americans opposed Philippine colonization

After the United States defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the European superpower ceded control of its colonies, which included the Philippines. At the same time, Filipino nationalists fought for their independence and wanted to pursue it despite the country’s annexation to the United States.

The U.S. refused to cede control of the country, however, ordering combat between American military and Filipino soldiers. The Philippine-American War lasted from 1899 to 1902. It resulted in the loss of life of an estimated 4,200 Americans and 20,000 Filipino combatants, as well as 200,000 Filipino civilians.

Historian Timothy D. Russell wrote in a 2014 journal article that African American soldiers were torn between their “sense of duty, discipline and identity as soldiers” and their sympathy for Filipinos—other people of color—who also felt the yoke of white supremacy.

As a result, a few African American soldiers deserted during the war, took the Filipinos’ part in combat, or were stripped of rank. Prominent Black American political activists, such as Ida B. Wells, condemned the American government’s actions. “Negroes should oppose expansion until the government was able to protect the Negro at home,” she wrote in January 1899 in the Cleveland Gazette.

The Japanese American Citizens League paved the way for affirmative action

The Japanese American Citizens League, founded in 1929, quickly became an influential lobbying organization post-World War II. The firm frequently visited Washington D.C. and spoke about workplace discrimination, job losses, and civil rights for all people of color.

As the federal government became more involved in creating discrimination laws and desegregation plans, JACL played a significant role in ensuring the term “minorities” incorporated a broad group of people in need of workplace protection. The organization appeared in civil rights efforts and filed briefs in support of workplace protections, as well as school and housing desegregation.

In particular, JACL emphasized a campaign led by Black activists to make a temporary Fair Employment Practices Committee into a permanent fixture. An FEPC would benefit not just Black Americans and Japanese Americans but also a swath of people typically seen as minorities at the time.

In the words of Ina Sugihara, co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality’s New York chapter and organizer at JACL’s first multiracial chapter in New York, “The fate of each minority depends upon the extent of justice given all other groups.”

Lawmakers would introduce more than 100 FEPC bills to Congress, but each attempt was shot down. The idea, however, would eventually evolve into an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission within the Civil Rights Act of 1964, giving birth to the concept of “affirmative action.”

Black and Asian American activists came together to repeal the Emergency Detention Act

The Emergency Detention Act of 1950 was part of a slew of McCarthyist policies during the Cold War that would allow the federal government to detain anyone suspected of espionage and build detention facilities to hold them.

Its opponents called the legislation the “concentration camp law” because it would allow the government to round up and imprison anyone they thought could be a security threat—precisely what they did to more than 100,000 Japanese Americans in World War II.

In the late 1960s, as the fear of communism tangled with the Civil Rights Movement and civil disobedience, the fear that the government would use the Emergency Detention Act to jail Black activists grew. San Franciscan Asian American students began protesting concentration camp legislation and eventually pressured the JACL to formally lobby against the Emergency Detention Act, following efforts by Black activists. In 1971, the act was repealed.

The Rainbow Coalition pushed for change

The first Rainbow Coalition was established in 1969 in Chicago by Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party to form alliances with other groups and working-class communities in a deeply segregated city. The movement eventually expanded to include the Red Guard (a Chinese American youth movement), the Puerto Rican Young Lords Organization, the Mexican American United Farm Workers, the white Appalachian Young Patriots Organization, and the American Indian Movement.

Strengthened by these allegiances, organizers would boycott and walk picket lines together, as well as attend each other’s rallies and demonstrations. Members of these various organizations would collaborate to help alleviate street gang violence, launch free breakfast programs, and operate daycare centers.

The start of ethnic studies in classrooms

In the 1960s, the Black Student Union at San Francisco State demanded that the school offer a history course more aligned with the Black experience. The movement grew into the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of Black, Latino, Asian, and Indigenous student groups in San Francisco. The university became the first school to teach an ethnic studies class.

In 2021, California became the first state to make ethnic studies a requirement to receive a high school diploma. Though some groups have denounced the legislation for sowing division, Penny Nakatsu, a civil rights lawyer in San Francisco, disagrees. “Ethnic studies is a way of embracing all of the cultures that make up the world,” she told KQED. “If we don’t understand each other, how are we going to get along?”

Vietnamese and Black Americans rebuilt after Hurricane Katrina

After Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans, Vietnamese and African American residents supported each other as they rebuilt their communities.

In 1975, Catholic Vietnamese immigrants made their way to New Orleans after being uprooted many times before—first from northern Vietnam during a French-led conflict and again in the ’70s during the American-led Vietnam War. They lived alongside Black Americans in the South.

According to Dr. Eric Tang, an African Diaspora Studies professor at the University of Texas at Austin, Vietnamese Americans and Black Americans collaborated post-Katrina to prevent developers from profiting from the disaster. They also vocally denounced government organizations for inadequately supplying New Orleans residents with recovery resources and protested the site of a landfill—one of the many ways environmental racism plays out in communities of color.

During the hurricane, Father Nguyen The Vien, head of the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church, organized evacuation attempts in the Versailles neighborhood. The church served as a temporary shelter for the first people who returned to New Orleans after the storm.

Story editing by Carren Jao and Jaimie Etkin. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

![]()