Fentanyl test strips save lives, so why are they illegal in some states?

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Ciano // Stacker // Getty Images

Fentanyl test strips save lives, so why are they illegal in some states?

Gloved hands holding test strip with row of test strips in background.

Drug overdose deaths driven by fentanyl have risen sharply over the past decade, underscoring an ongoing—and worsening—American opioid epidemic leaving a staggering loss of life in its wake.

Yet despite attempts to mitigate overdoses using fentanyl test strips, several American states still regard this proven harm-reduction strategy as an “aggravator” of the opioid epidemic, classifying the test strips as drug paraphernalia under the law.

Ophelia used data from the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to explore where fentanyl and xylazine test strips remain subject to drug paraphernalia laws.

Fentanyl—the primary cause of overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids between 2015-2022, according to a National Institute on Drug Abuse analysis—is an extremely potent and widely available synthetic opioid about 100 times more potent than morphine. While serving a legitimate medical purpose under supervision from licensed medical professionals, fentanyl is a growing threat to human health and life in the illegal drug market. There, it’s mixed into other drugs to increase potency or pressed into pills that otherwise appear to be legitimate prescription opioids. Just 2 mg of fentanyl can be lethal.

Public health officials have invested in test strips to identify fentanyl, a strategy that follows other harm-reduction strategies, like safe needle exchanges. Making the overdose-reversal medication naloxone (Narcan) more widely available is a similar research-backed approach to reducing drug use. Fentanyl test strips offer a low-cost way for individuals who use drugs to test and identify the materials in any water-soluble drug, which can allow them to make informed, safer decisions.

Under federal law, drug paraphernalia includes any equipment used to “produce, conceal, and consume illicit drugs.” Though states vary in their application of this definition and in the consequences of possession, paraphernalia includes pipes, bongs, and cigarette papers.

The DEA classifies drugs into five schedules based on their potential for dependency and acceptable use in the medical field. Schedule I drugs include those without approved uses and high potential for abuse, such as heroin, while Schedule V drugs include those with low potential for misuse, such as codeine, commonly found in cough syrups. Fentanyl is classified as illicit under Schedule II, along with cocaine, methamphetamine, oxycodone, and Adderall.

Harm reduction emphasizes risk reduction and health promotion among people who use drugs. This community-driven approach, designed to foster incremental change toward treatment and recovery, is a cornerstone of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Overdose Prevention Strategy. Harm-reduction strategies have demonstrably reduced drug usage and, in some cases, prevented the spread of disease. Syringe services programs, for instance, result in 50% fewer HIV and Hepatitis C virus cases; those who use SSPs are three times more likely to quit their choice drug owing to program referrals, according to CDC data.

Strategies enabling a person to use their choice drug safely might seem counterintuitive, and the tension between these strategies and the laws criminalizing them pushes people to secrecy. In Pennsylvania, for instance, government officials revoked $150,000 in opioid settlement money from a harm-reduction nonprofit when their owner spoke out about syringe services.

Harm-reduction strategies emerged in the wake of the punitive “War on Drugs” era after arrests and incarcerations proved an ineffective deterrent to drug use. Growing awareness that immediate abstinence is not always possible for those coping with addiction. On average, it takes approximately five attempts to overcome an alcohol or drug problem, according to a 2019 study by the Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

![]()

Ophelia

Fentanyl testing

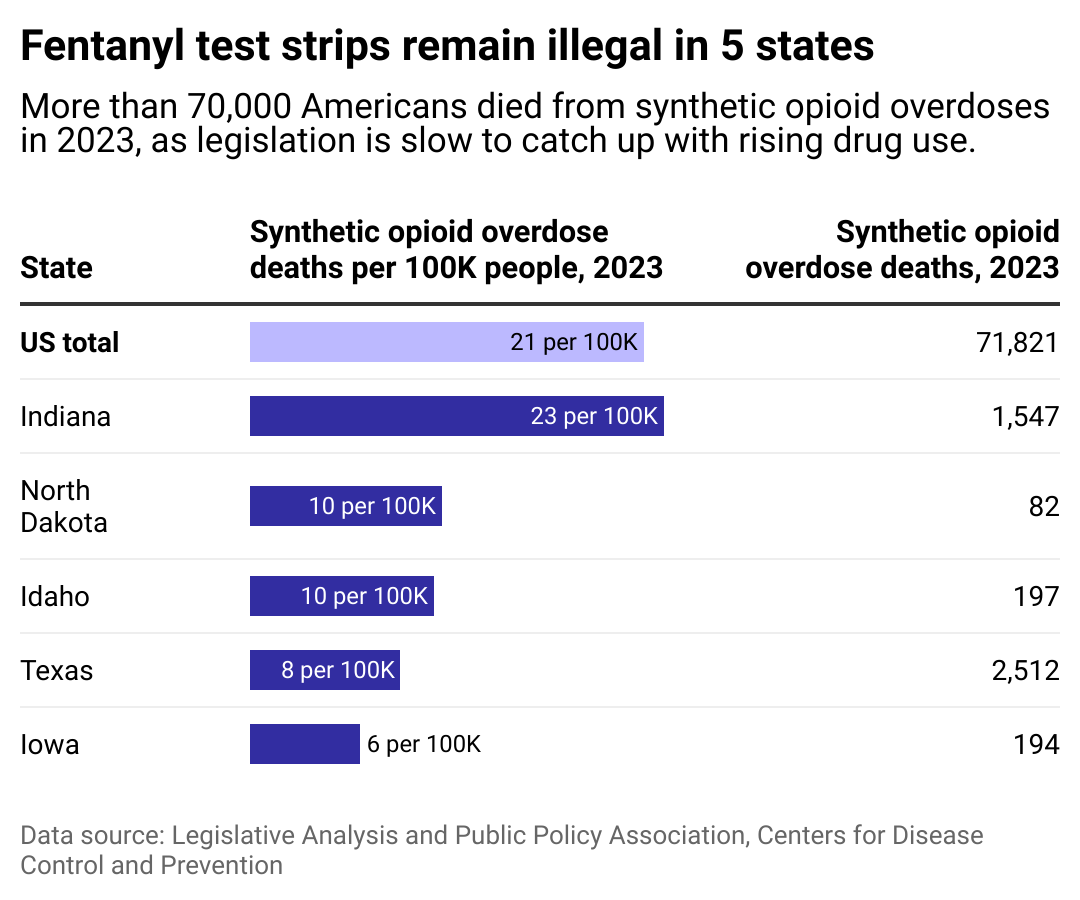

Table showing the five states fentanyl test strips remain illegal. They are Indiana, North Dakota, Idaho, Iowa, and Texas. Indiana reports the highest rate of synthetic opioid overdose deaths among the states where fentanyl test strips are subject to drug paraphernalia laws.

Despite being an accurate and affordable harm-reduction strategy, fentanyl testing strips are still illegal under some drug paraphernalia laws. In the five states where they remain illegal, legislative decriminalization efforts have failed in two and are ongoing in one.

Indiana ranks #13 in the nation in drug overdose deaths, according to the CDC. In the state’s Marion County, drug intoxication remained the leading cause of death in the region for the fourth year in a row in 2023, an average of two deaths per day. Per the Indianapolis EMS service, the state saw a 59% increase in 911 calls for potential drug overdoses in youth under age 17 between 2019 and 2024. However, legislative efforts to decriminalize fentanyl test strips failed in February 2024.

In North Dakota, where the overdose rate increased by 75% in four years, fentanyl played a role in 303 of 496 drug overdose deaths between 2019 and 2023, according to data from the North Dakota Violent Death Reporting System. Test strips remain illegal under the state’s paraphernalia laws, with no reported planned legislative efforts to decriminalize them.

Under existing drug possession statutes, Idaho does not even exclude program staff who conduct drug testing from drug possession penalties. However, the Idaho House voted 70-0 in February 2024 to legalize fentanyl test strips. The bill is currently awaiting the Senate.

Efforts have faced fierce opposition. A Texas bill to decriminalize fentanyl test strips passed in the state House in April 2023 but failed in the Senate despite bipartisan support, including Gov. Greg Abbott’s approval: a reversal of his prior stance on the initiative.

In Iowa, drugs seized containing illicit opioids increased fivefold between 2022-2023 and were responsible for 89% of opioid deaths, according to the Governor’s Office of Drug Control Policy. Still, fentanyl test strips remain illegal and are considered paraphernalia in the state. Test strips were even blocked from being included in public harm-reduction boxes in 2022.

Notably, other U.S. regions have taken a different tact in response to the opioid crisis, embracing harm-reduction strategies. For example, some cities, including Washington D.C. and Cincinnati, recently launched anonymous vending machines with Narcan and other harm-reduction products, aiming to reduce barriers to access.

Ophelia

Xylazine testing

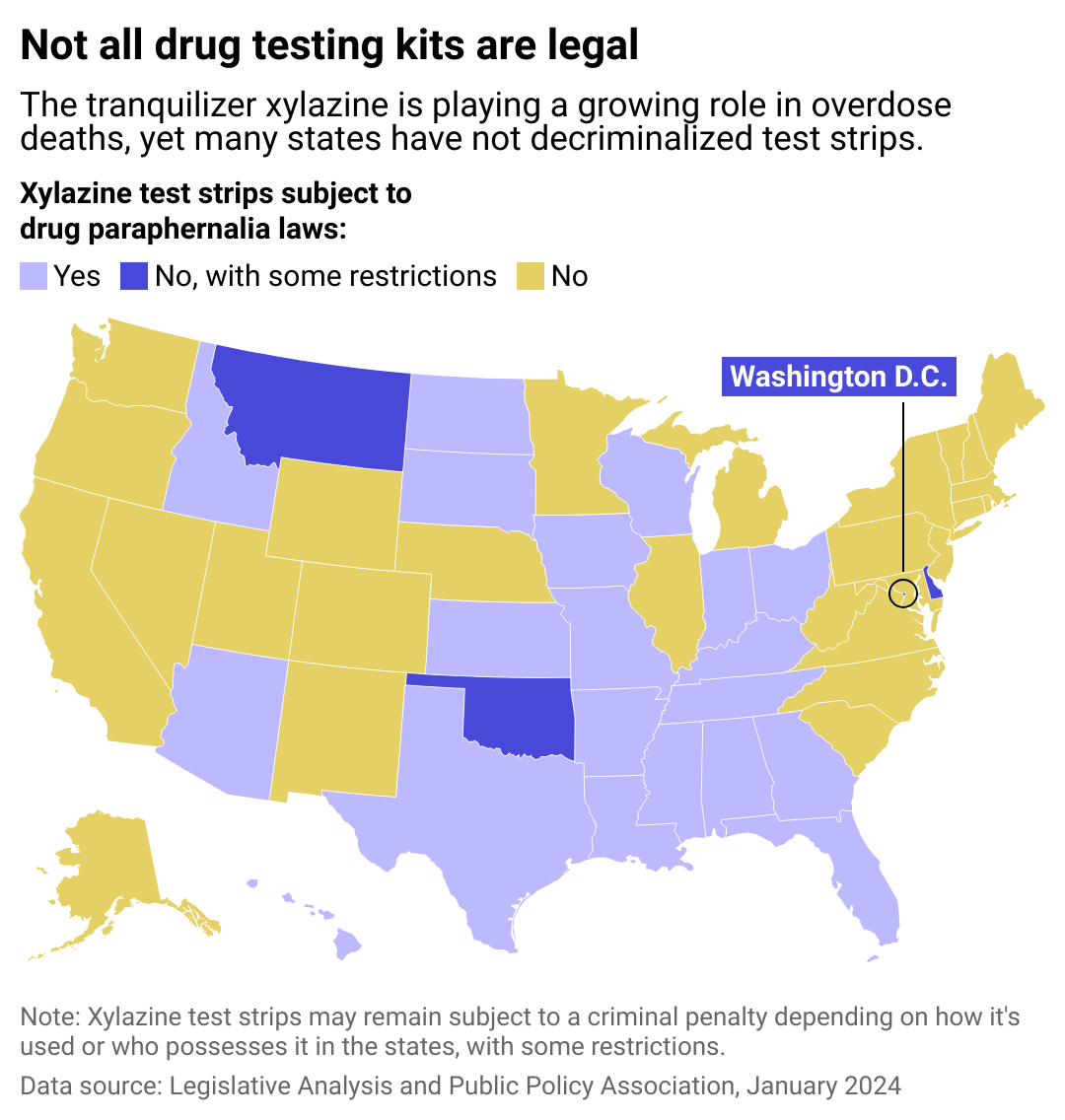

Map showing the 20 states where xylazine testing remains illegal.

Xylazine, a veterinary sedative known as “tranq,” has entered the American illicit drug supply in recent years. Illegal drug manufacturers mix xylazine with fentanyl, as well as with other drugs like cocaine and heroin, to increase the drugs’ effects and duration. Though not as common as fentanyl, the powerful drug has been responsible for a growing number of overdose deaths.

According to the DEA, the presence of xylazine in the Southern United States increased by a staggering 193% between 2020 and 2021 and by 112% in the Western United States during the same period. Despite tranq’s clear threat, most Southern states still consider xylazine test strips as paraphernalia under the law, including Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida.

Additionally, a CDC study of 21 jurisdictions between January 2019 and June 2022 found that deaths due to illicitly manufactured fentanyl containing xylazine increased by 276%.

Last year, the drug was classified as an “emerging drug threat”. In response, the Biden administration has implemented a response plan to fentanyl combined with xylazine, while the bipartisan TRANQ Research Act aims to increase research into xylazine detection and response.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.