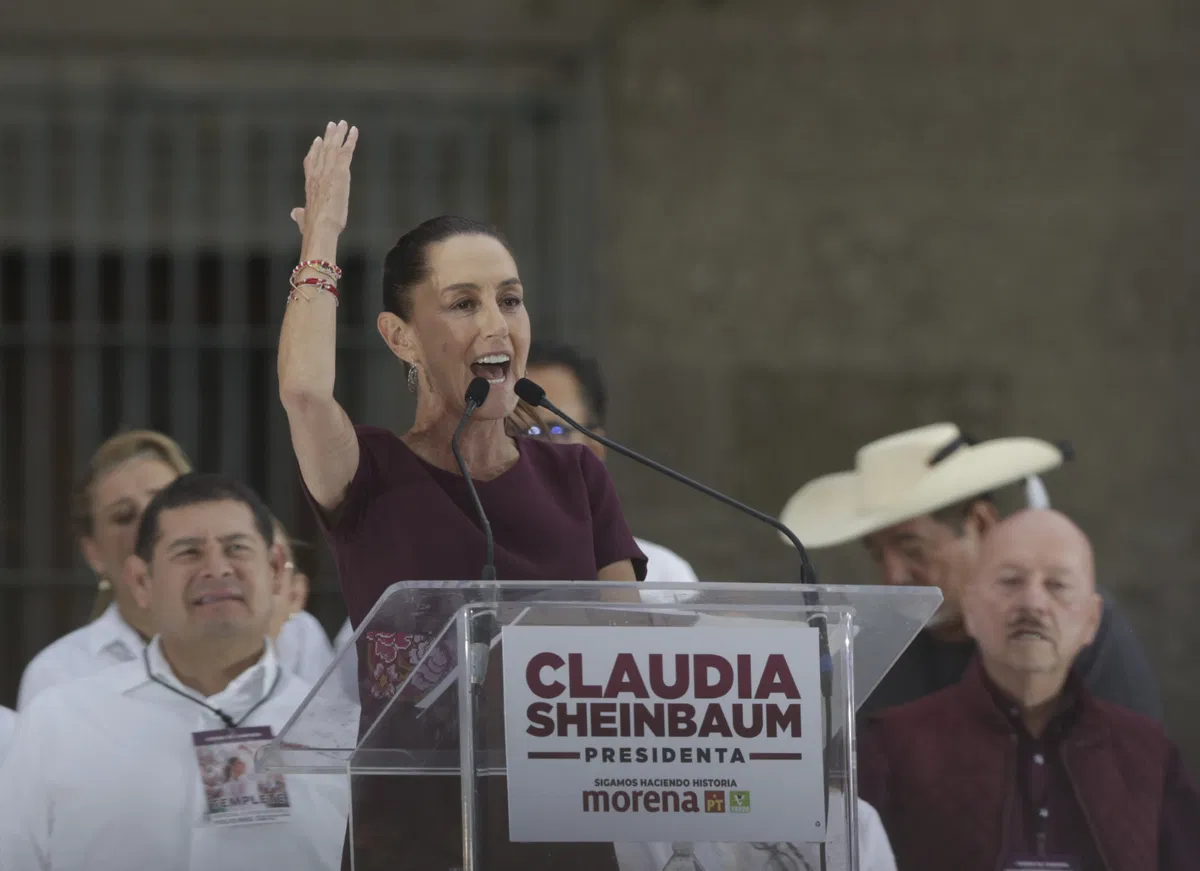

Claudia Sheinbaum: Her rise to power and her future as Mexico’s president

By Eduardo García and Alfredo Corchado

Words by Eduardo Garcia, Alfredo Corchado Photos by Omar Ornelas Edited by Dudley Althaus, @dqalthaus

Puente News Collaborative is a bilingual nonprofit newsroom, convener and funder dedicated to high quality, fact-based news and information from the U.S.-Mexico border.

MEXICO CITY – When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, then-Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum quickly re-purposed the sprawling Mexican capital’s public security center, the C-5, into a hub for handling emergency calls and coordinating medical assistance.

The C5’s surveillance cameras, previously used to monitor traffic and crime, were deployed to guide ambulances through the city’s sprawling, labyrinthine streets. The strategy ensured that emergency vehicles could reach their destinations quickly, transporting patients to the nearest available hospital or clinic.

“When we arrived at C5, there was already a large map of the city, and you could see illuminated dots showing the locations of all the ambulances from different organizations,” recalled Carlos Mackinlay, then Mexico City’s Tourism secretary who helped coordinate the effort. “You could even communicate with the ambulances to find out why they stopped or if they needed additional equipment."

Sheinbaum’s swift response to the health crisis in early 2020 has raised hopes among millions of Mexicans that she will bring similar pragmatic efficiency to the national government after becoming the country’s first female president on Tuesday.

Sheinbaum won the presidency in June’s election by a landslide, with 59 percent of the votes cast. Her center-left Morena party also controls Mexico’s national Congress and more than two-thirds of its 32 state governments.

Many who have worked closely with the new president highlight her rigorous and results-driven attitude —qualities probably honed during an academic career in science and technology.

Sheinbaum, 62, holds a doctorate in engineering from Mexico’s National Autonomous University and did postdoctoral studies at the University of California-Berkeley. She contributed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

“She is organized and structured. She conducts short, executive meetings with concrete, precise orders and clear demands,” Mackinlay said, before adding that Sheibaum also is “a woman with profound social and political convictions.”

The greatest concern among her opponents, however, is whether the new president will be able—or willing—to step out of the shadow of outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, her longtime mentor.

Either compelled to or by conviction, these critics fear, Sheinbaum will march in lockstep to her predecessor’s beat.

Indeed, Sheinbaum has backed Lopez Obrador’s key policy priorities throughout her political career. Those include reducing private-sector involvement in the energy sector and advocating for a strong state role in alleviating poverty.

“I am part of a social movement,” Sheinbaum proudly declares in a 40-minute documentary about her life.

A renewed confrontational stance toward Washington and a flurry of constitutional changes made in September –including reforms that increase political control over the judiciary and place all federal security forces under military administration– have people anxious at home and abroad.

As a result, some analysts see Sheinbaum’s six year presidency as starting with “one hand tied behind her back”, with her ability to maneuver sharply defined.

“López Obrador didn’t just handpick Claudia.” said Lila Abed, director of the Mexico Institute at the Washington-based Wilson Center. “He also selected many of the current deputies, senators and governors who are loyal to him, not necessarily to her.”

Many Mexicans, including López Obrador himself, believe she will not change course as president, in part because mellow is not what she does. Certainly, Sheinbaum identifies as a left-wing politician rooted in much the same anti-market and nationalist vision that López Obrador has long championed.

“Some think that once I leave, things will go back to the way they were before, or that the government will be more benign,” López Obrador said in a recent press conference. “No, no, no. I’m taking this opportunity to warn you, I’m the benign one.”

Not surprisingly, Sheinbaum faces widespread skepticism amid her opponents and democracy advocates.

Their doubts also feed on several controversial decisions she took during her tenure as mayor.

During the pandemic, her government distributed nearly 200,000 medical kits containing Ivermectin, a drug typically used to treat animal parasites, to individuals who had tested positive for the coronavirus. These individuals were not informed that they were part of an experimental cure that later was determined ineffective.

After a section of an elevated subway line collapsed in southern Mexico City, killing 26 passengers and injuring 98, Sheinbaum sought to withhold politically damaging parts of an independent report she had commissioned to investigate the cause.

The report by a Norwegian group attributed the tragedy primarily to poor construction techniques and supervision, which took place two administrations before hers. Still, the findings criticized Sheinbaum’s administration for failing to conduct proper maintenance checks that could have prevented the tragedy.

The new president’s left-leaning political activism began in the crib.

Her parents, children of Eastern European and Middle-East secular Jews who immigrated to México in the early 20th Century, took part in the 1968 student movement that demanded more political openness. That movement was squelched by the government, including the slaughter of dozens by security forces in the so-called Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2 of that year.

Sheinbaum herself participated in later social movements, including the long and bitter student strike which paralyzed Mexico’s national university for 10 months at the turn of this century. While studying at Berkeley, Sheinbaum protested the visit of Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who pushed free-market policies while resisting democratic reforms.

"Fair Trade and Democracy Now!!" demands a placard Sheinbaum is holding at the protest.

That activist impulse could pose challenges for the next U.S. president, whoever she or he might be. For his part, Donald Trump has threatened to impose sanctions and even invade Mexico or bomb drug cartels’ labs to clamp down on organized crime.

“I think that is on the table, and I don’t think we can take it lightly”, said Abed.

Such threats while Trump was president proved effective saber rattling in winning concessions on immigration from López Obrador and his Mexican predecessor. How Sheinbaum might react is an open question.

With the two countries sharing a 2,000-mile border, Mexico is the U.S.’s largest trading partner and a key ally in managing illegal immigrants and narcotics trafficking gangs using the country as a springboard.

Under U.S. pressure, Mexico has cooperated in suppressing much of the immigrant traffic –if not the narcotics– heading north.

But Mexico’s seeming shift toward what critics see as a one-party state under López Obrador’s final stretch of his six-year term has raised alarms in Washington. If left to fester, this could strain Sheinbaum's relations with the White House and Congress, analysts say.

Still, a confrontation with the U.S. may not be in Sheinbaum or Mexico’s interest as its northern neighbor it’s not only its largest trading partner, but also the prime source of investment and remittances.

Certainly, Sheinbaum faces very different circumstances from those López Obrador encountered when he took office six years ago, including a more depleted public treasury.

Despite improving the lives of millions by state grants, López Obrador has also poured enormous resources into still-unprofitable projects like a new oil refinery, a tourist train in the Yucatan Peninsula and a little-used second airport in Mexico City. The first two projects have cost two or three times more than originally planned and the three will require subsidies to stay afloat.

Additionally, the state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, is a basket case. Despite more than $50 billion in government bailouts over the past six years aimed at boosting production and refinery capacity, Pemex is still losing billions over the past six years, mainly from its refinery division.

The recent judicial reforms threaten to undermine foreign investors’ confidence in Mexico, which is essential for economic growth and poverty alleviation.

Finally, an array of criminal gangs has gained effective control over nearly a third of Mexico’s territory, pursuing extortion and other rackets that impact local communities far more than does international trafficking of narcotics.

As well as Sheinbaum, López Obrador inherited hyper-violence largely owing to underworld turf fights that began in 2006. As many as 30,000 people have been killed each year since 2018, according to the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations, while more than 45,000 have been reported missing or presumed dead during the last six years.

López Obrador disputes the tallies, claiming they have been inflated to damage him politically.

Many hope that circumstances will compel Sheinbaum to adjust course, even if only slightly, from López Obrador’s project, which he romantically characterizes as the Fourth Transformation in Mexico’s history. Even if she doesn’t want to, they argue, Sheinbaum must tread carefully to fulfill her stated belief that “governing is serving the people.”

In her heart Sheinbaum “may be even more nationalist and left-leaning than López Obrador,” said Duncan Wood, president of the Pacific Council on International Policy, a think tank focused on U.S.-Mexico issues.

Still, he said, reality may bite.

“She is an academic, a scientist. If you look at her cabinet appointments since she won the election, you see a balance between left and right, closed and open,” Wood said in a recent conference in Austin.

“I think we’re going to see a president who is more diplomatically open toward the U.S. than her predecessor.”

Dudley Althaus edited story