Americans are saving the least they have since 2005. Here’s why that matters.

Canva

Americans are saving the least they have since 2005. Here’s why that matters.

A calculator and stack of cash lie atop a downward-pointing graph.

Unusual. Historic. Concerning. These are terms economists use when they look at American saving habits today. Stacker examined what the decline in savings means for the future financial health of the average American.

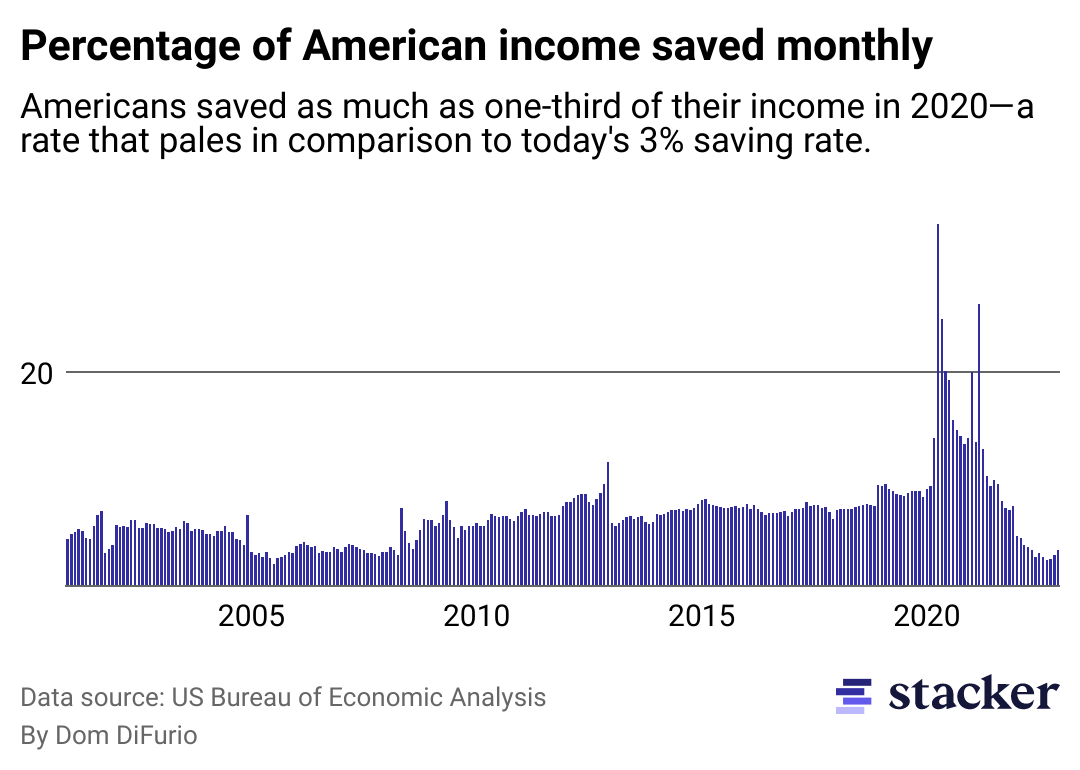

Consumers saved about 3.4% of their monthly income in December, a slight uptick from November’s 2.9%, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That figure has hovered around the lowest since 2005 when the United States was careening toward the Great Recession.

At the same time, data suggests Americans have continued spending at rates above pre-pandemic norms. And they’re putting even more expenses on credit cards—a trend that began to pick up in the summer of 2021.

The rate is “unusually low,” said Anthony Murphy, a senior economic policy adviser for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The Personal Saving Rate, a figure economists watch to keep a pulse on the health of consumers from month to month, measures how much income Americans are storing away in a bank account. It is not a measure of the actual amount of money sitting in savings accounts or the equity they may hold in real estate or the stock market.

The saving rate provides a sense of how American consumers are behaving at the moment: what decisions Americans are making today as they think about the future and how they’ll cover expenses down the road.

As low as the rate is now, it might not be rock bottom, said Olivia S. Mitchell, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, where she researches retirement and saving behavior. She said the savings rate could turn negative in 2023, meaning households are spending more than they make in income.

![]()

Dom DiFurio

‘The big unknown’

This graphic shows the change in Americans’ savings rates from 2000 to 2022.

In early 2020, the pandemic’s impact on spending and the thousands of dollars in stimulus checks approved by Congress made it possible for Americans to squirrel away a record $1 out of every $3 they received.

“I’ve never seen a number like that,” Mitchell said.

As Americans save far less in recent months, analysts and experts have varying views on how long it will be before all that stashed cash runs out.

“The big unknown really is…will there be a recession?” Mitchell said. A recession, she said, would mean Americans may have a harder time finding consistent employment and building their savings back up.

Without padding in savings accounts, consumers run the risk of an emergency expense causing them to fall behind, or even default, on debt payments for a vehicle, home, or rent. There is evidence, for example, that an increased number of Americans defaulted on their vehicle loans last year, according to Cox Automotive, though the rate remains below historical standards.

The last time that Americans were saving as little month-to-month as they are today was in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis. From 2010-2020, the U.S. saving rate hovered around 7% of income.

The saving rate actually turned negative in 2005, causing debate among economists as to whether a “reckoning for consumers” was “finally” in store. They received their answer in 2007 as lenders began to collapse due to the poorly structured loans that helped fuel consumer spending on homes.

The silver lining for this current moment, according to economists like Mitchell, is that many Americans who want to work have jobs, as evidenced by the continually low unemployment rate. Americans who have set financial goals actually say they’re optimistic about making financial progress in the year ahead, according to a January 2023 survey from Morning Consult.

In December, just 5.7 million Americans were unemployed despite wanting a job, a total of about 3.5% of the working population, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That rate is also a low figure for the U.S., which required nearly a decade of job creation and recovery to reach following the Great Recession.

Paycheck to paycheck

The National Bureau of Economic Research has yet to officially declare a recession. Still, Bankrate senior analyst Mark Hamrick in a statement called the prospect of a recession “concerning.” Economists are generally watching to see when, and if, layoffs may spread beyond the tech sector, which has seen 200,000 job cuts since the start of 2022.

That’s because mass layoffs could impact whether the current financial profile of the American consumer is sustainable.

More than half of Americans say that if they had to pay for a one-time $1,000 emergency expense they would not do it with savings, according to Bankrate’s annual Emergency Savings Report conducted in December 2022. Instead, 25% of respondents told Bankrate they would sooner cover that expense with their credit card, and others said they would use personal loans or other means. That’s the sentiment even as credit debt is at a recorded high and interest rates on credit cards are climbing.

Bankrate has performed its survey since 2014 and said the 1-in-4 response rate on its question about covering an emergency expense with credit was a record high.

“Too many Americans continue to live paycheck to paycheck,” Hamrick said in a statement.

But there’s evidence that consumers are feeling the impact of the current economy differently— and that some are hurting more than others. Murphy, with Dallas Fed research analyst Aparna Jayashankar, published a study in January 2023 at the showing that the high inflation of the past two years has disproportionately negative consequences for low-income Americans. Black and Hispanic consumers as well as those who rent especially are feeling the squeeze, the study’s authors found.

“Those [pandemic era] savings are gradually being worn down,” Murphy said. “And at the lower [income] end, I’d say they’re largely exhausted for a lot of people.”

Throughout history, Americans tend to save more during recessions, Murphy said. The slight uptick in the saving rate to 3.4% in December could be a sign of economic trends to come, though he acknowledges that the saving rate can be “a little volatile” from month to month.

Mitchell advised that as Americans look ahead, “a sensible path would be to start drawing down on savings before taking on more credit card debt.”

For now banks are tightening their lending standards and the credit cards they’re handing out are carrying higher interest rates—especially for users with less-than-good credit, Murphy said.