How access to naloxone medication like Narcan—used to reverse opioid overdoses—varies in each state

Brittany Murray/MediaNews Group/Long Beach Press-Telegram via Getty Images

How access to naloxone medication like Narcan—used to reverse opioid overdoses—varies in each state

Hand holding Narcan nasal spray package.

In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed alarming news: Every day of 2021, 220 Americans died from an opioid-related overdose. That was five years after President Donald Trump’s administration announced the opioid epidemic was a national public health emergency.

The CDC began collecting data on overdoses nationwide, whether fatal or not, in 2019. So far, 49 state governments, and Washington D.C., have participated in this effort. Local agencies in 24 states are also involved.

In 2020, the Biden administration made $1.5 billion in federal funds available for states, territories, and tribes to address the overdose epidemic through recovery programs. It also expands access to medications that can reverse overdoses, such as naloxon, which is commonly referred to by its brand name Narcan.

When a person has opioids in their system, naloxone—which is also known as Narcan and sprayed into the nose or injected into the muscle or veins—binds to opioid receptors in the brain and blocks the effects of the opioids. It is an effective life-saving medication, reversing opioid overdose in a matter of minutes and lasting long enough for a person to get emergency medical attention. However, critical to saving lives from opioid overdose is access to naloxone for those who need it, and access to the drug varies by state.

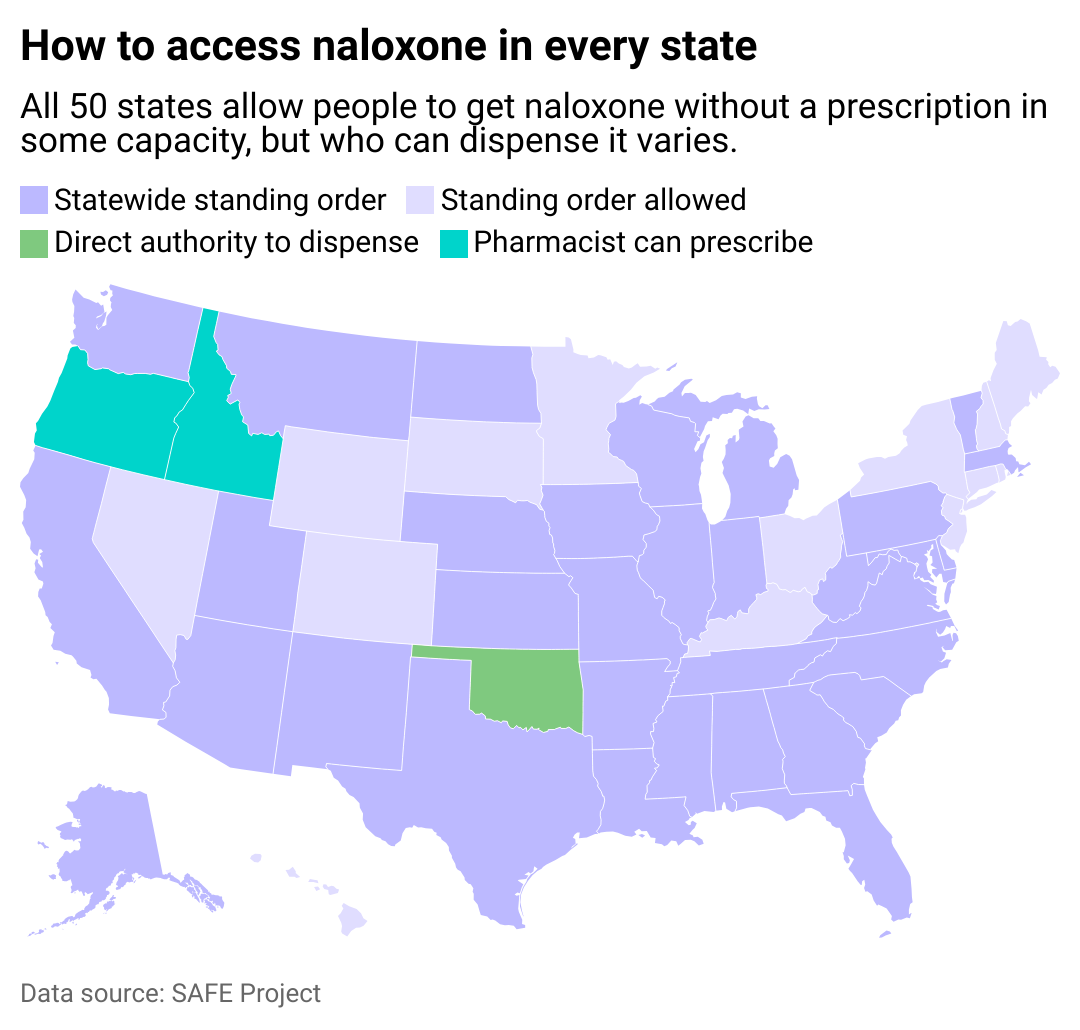

In recent years, all 50 states have passed legislation facilitating access to naloxone. The different statutes highlight the effectiveness of the medication in saving opioid users’ lives. Ophelia examined how naloxone access varies by state using data compiled by the SAFE Project, a nonprofit organization working to combat America’s addiction epidemic.

In most states, standing orders from the state public health agency allow first responders, family and friends of at-risk consumers, community organizations, law enforcement agencies, recovery centers, or anyone who might find themselves in a situation where someone is overdosing to request or purchase naloxone without a prescription. In many states, users need basic training in administering the drug before being allowed to carry it.

![]()

Ophelia

Naloxone access by state

A map showing how residents can get naloxone in each state.

In 33 states, public health officials have issued a statewide standing order allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone to people even if they do not have a specific prescription for the medication. These orders include specific directions for who can receive the medication. In most states, that includes people who use opioids and, therefore, might experience an overdose, as well as official first responders like police officers, firefighters, and ambulance workers.

Also typically eligible under statewide standing orders are users’ family members, friends, and caregivers because they might encounter someone during an overdose. In many states, members of the general public who might come upon or find themselves near a person experiencing an overdose are also eligible to get naloxone.

Standing orders typically allow a person to receive one or two rescue doses of naloxone, often along with information or brief training about how to prevent overdoses, spot them, and use the medication. Just because a state has a standing order does not mean naloxone is free, though most states have places or programs that offer free naloxone to qualified recipients.

In 14 states and the District of Columbia, physicians are allowed to issue standing orders to specific pharmacies or pharmacists, in which the doctors specify who can receive the medication without a prescription and under what conditions.

Idaho and Oregon still require prescriptions for naloxone—but pharmacists, not just doctors, can issue it. Then, the pharmacists can dispense the medication to that person.

In Oklahoma, state law says people do not need a standing order or a prescription: Pharmacists can dispense naloxone to anyone, though there can be a cost. There is also a standing order in effect.

George Dodd III // Shutterstock

#1. Alabama

Aerial view Mobile skyline.

With two laws passed in 2015 and 2016, Alabama allows pharmacists to provide naloxone to first responders as well as anyone who might be around or encounter someone overdosing on opioids.

People can also request free online training on administering Narcan and Kloxxado, a different brand name for the naloxone nasal spray. The state’s health department provides plenty of online information about the life-saving medication, including a downloadable and printable “overdose response resource card” with information about how to get naloxone and help for addiction.

mffoto // Shutterstock

#2. Alaska

Aerial view of Haines city.

State law allows anyone at risk of overdosing or who might be in a position to assist someone experiencing an overdose to get naloxone.

In 2018, the Office of Substance Misuse and Addiction Prevention of Alaska created a five-year statewide plan to reduce drug misuse and abuse, partly to reduce overdose deaths, including a recommendation that health providers recognize opioid addiction as a chronic disease.

Gregory E. Clifford // Shutterstock

#3. Arizona

Scenic view of Phoenix.

The state has a standing order allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone without needing a prescription. In addition, state law says someone who gives another person naloxone or another opioid-overdose drug “in good faith and without compensation is not liable for any civil or other damages as the result of the act.”

The Arizona Department of Health Services recommends clinicians and first responders follow CDC opioid guidelines, including carefully considering whether a patient’s situation requires opioids instead of other painkillers to prevent unnecessary use and reduce the risk of dependency.

Eduardo Medrano // Shutterstock

#4. Arkansas

Afternoon Little Rock cityscape.

Arkansas’ law allows licensed health care providers, including pharmacists, to make naloxone available to anyone at risk or in a position to assist someone at risk. The state health department has a standing order for dispensing and administering naloxone, highlighting risk factors for overdose, which are not just past opioid use but also the use of other drugs, tobacco, and alcohol.

The order warns that a person who receives naloxone may experience “acute withdrawal symptoms” such as nausea, diarrhea, fever, body aches, anxiety, and disorientation.

Canva

#5. California

Tower Bridge and Capitol Mall.

A statewide standing order permits community organizations to dispense naloxone without a prescription to a person at risk or in a position to assist a person at risk. It also allows licensed health care providers, including pharmacists, to make naloxone available to anyone.

A state law passed in 2019 requires any medical professional who prescribes high levels of opioids or any amount of opioids in conjunction with a certain type of depressant drug to issue the patient a naloxone prescription. The law also requires prescribers to distribute information on overdose prevention to patients and caregivers.

John Hoffman // Shutterstock

#6. Colorado

Colorado Springs cityscape in autumn.

About 17,844 people have died in Colorado due to an opioid-related overdose since 2000, according to the anti-overdose organization Stop the Clock Colorado.

Colorado health officials approved the dispensing of naloxone through a standing order, allowing pharmacies, licensed physicians, and mental health professionals to dispense naloxone without a prescription to someone at risk or in a position to assist someone at risk, as well as to first responders and harm reduction organizations.

The standing order “covers the possession and distribution of naloxone kits,” including intramuscular injections and nasal atomizers, but does require the recipients to receive training on administering the drug.

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock

#7. Connecticut

Skyline of downtown Hartford from above Charter Oak Landing.

Since 2012, anyone in Connecticut has been able to get naloxone without a prescription. Two years later, another law clarified that anyone who administers naloxone to a person in need is protected from civil and criminal liability.

A 2019 law prevents life insurance companies from denying coverage to people who have received a naloxone prescription. It also requires hospitals and ambulance workers to report overdoses to state officials.

Paul Brady Photography // Shutterstock

#8. Delaware

Wilmington riverwalk.

A standing medical order in Delaware authorizes the distribution of naloxone to anyone who has completed a one-hour training course on administering the drug.

In Delaware, naloxone is free and can be ordered by mail, according to the state’s Help Is Here initiative. The program also offers recommendations on how to deal with addiction and links to emergency and crisis services.

pisaphotography // Shutterstock

#9. Florida

Miami Beach aerial view.

In September 2022, the Florida Department of Health authorized a statewide standing order that allows registered health care practitioners and pharmacists to dispense naloxone to patients, caregivers, and first responders without a prescription.

State health offices also offer naloxone for free to anyone 18 and older at risk of an opioid overdose, someone caring for an at-risk person, or someone who may likely encounter a person having an overdose.

Brett Barnhill // Shutterstock

#10. Georgia

Elevated view of Atlanta skyscrapers and cityscape.

In 2019, the state Public Health Department issued a standing order allowing anyone to get naloxone either as a nasal spray or a syringe for injection. The state aims to enable “the widest possible availability of naloxone among the residents” of Georgia.

State officials also encourage people to become familiar with the symptoms of an opioid overdose, such as a pale face, bluish fingernails and lips, vomiting, inability to wake up or speak, or slow breathing and heartbeat. Free courses, including online videos, teach people how to administer the drug. The training is recommended, not required.

MNStudio // Shutterstock

#11. Hawaii

Honolulu waterfront and cityscape.

In 2018, Hawaii lawmakers passed a law allowing health care providers, including pharmacists, to make naloxone available to anyone at risk or in a position to assist someone at risk, or to a harm reduction organization.

The law says unintentional drug overdoses are “one of the leading causes of injury-related mortality in Hawaii” and cost the state nearly $10 million in hospital costs in 2016 alone.

Charles Knowles // Shutterstock

#12. Idaho

Skyline of downtown Boise.

In Idaho, any health professional can prescribe, dispense, and administer naloxone or other anti-overdose medication to anyone under a state law passed in 2019. Naloxone is free in Idaho for Medicaid holders and anyone else—regardless of insurance coverage or lack thereof—through community help groups and addiction treatment centers.

marchello74 // Shutterstock

#13. Illinois

Chicago neighborhood buildings and city skyline on a sunny autumn day.

A statewide standing order allows health care professionals, including pharmacists, to give naloxone to anyone who requests it. Overdose education and naloxone distribution programs, which police may run, hospitals, local governments, private companies, or other community groups are also permitted to dispense the drug.

Anyone dispensing it must take a training course, including online videos, and promise to provide overdose-prevention training to anyone they dispense naloxone to.

Jonathan Weiss // Shutterstock

#14. Indiana

Indiana State House and Capitol Dome.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists and others to dispense naloxone to anyone who requests it, so long as the person or company doing the dispensing registers with state health officials each year. In recent years, the state government has spent more than $4 million to make naloxone more widely available throughout Indiana.

Dawid S Swierczek // Shutterstock

#15. Iowa

Historical buildings in downtown Dubuque.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription to a person at risk, someone who can help an at-risk person, or a first responder. Before being allowed to dispense it, the pharmacist must complete a training course and assess the recipient’s eligibility.

The state also asks pharmacists and other dispensers to download, print, and distribute an Iowa Department of Public Health “Opioid Recognition and Response” brochure.

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

#16. Kansas

Aerial view downtown Wichita.

Kansas provides free naloxone to community organizations and any state resident upon request. A statewide social service agency also runs training programs, both online and in-person, to make sure people know how to administer the drug and understand the context of the opioid crisis in Kansas and nationwide.

Canva

#17. Kentucky

Louisville skyline.

A 2015 law made clear that anyone who reports a suspected drug overdose or tries to help a person who may be overdosing is not civilly or criminally liable for being at the incident.

Physicians can instruct specific pharmacists to dispense naloxone as needed, and the medical director of the state’s Medicaid services department issued an order pharmacists can sign up to follow.

Nonprofits in the state have teamed up to mail naloxone to anyone who requests it. And the state maintains a website where people can find out where to get naloxone in person.

Canva

#18. Louisiana

Aerial photo Baton Rouge State Capitol Park.

State law and a standing medical order allow a pharmacist to dispense naloxone to anyone. Before dispensing it, the pharmacist must review at least three points with the person requesting the medication: how to recognize opioid-overdose signs, how to properly store and administer naloxone or other opioid antagonists, and the fact they need to call emergency services immediately before or after administering naloxone.

The drug is free in Louisiana for people on Medicaid, and other insurance companies cover some or all of the cost for their participants.

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock

#19. Maine

Portland Head Lighthouse and coastline.

Maine offers free naloxone—for nasal or syringe administration—to anyone anywhere in the state. Pharmacists with a standing order from a physician can also provide it to anyone at risk or in a position to help someone at risk. There is not a statewide blanket standing order.

Free training on how to use naloxone and how to prevent overdoses in the first place is also available—as is education on how to become a naloxone distributor. Once approved, distributors can teach the community about overdosing, enroll participants, and support policy reform, besides dispensing naloxone to friends and family of at-risk patients.

Real Window Creative // Shutterstock

#20. Maryland

Aerial view of Annapolis and the Statehouse.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone in Maryland. The state also keeps an updated list and a map of public Overdose Response Programs available online.

Those programs dispense free naloxone and opioid test strips upon request in person and, in some counties, by mail. No prescription, certification, or training is needed to order naloxone.

f11photo // Shutterstock

#21. Massachusetts

Boston skyline in winter.

The state has a standing order allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone—and state regulators require all pharmacies to stock it. Naloxone prescriptions in Massachusetts are covered by private insurance companies and by MassHealth, the state’s public health insurance plan.

The state’s Bureau of Substance Addiction Services provides overdose prevention and response training.

Vladimir Mucibabic // Shutterstock

#22. Michigan

Detroit skyline on clear day.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists who register with the state to dispense naloxone to anyone. The University of Michigan is working with a group of Ann Arbor businesses to teach employees how to administer naloxone as part of a statewide effort to make naloxone more available.

ostreetphotography // Shutterstock

#23. Minnesota

Downtown Minneapolis overlooking Mississippi River.

In 2023, Minnesota’s legislature required schools, prisons, police, and group homes to carry naloxone as part of a statewide effort to prevent overdose deaths. Pharmacists may dispense it without a prescription to people at risk or in a position to assist, as well as first responders and school nurses. Not all pharmacies carry naloxone, though.

The Minnesota Department of Health offers a Naloxone Finder map and a Syringe Exchange Calendar to help people find the medication, the cost of which at pharmacies depends on insurance coverage. There are community organizations that distribute it for free, as well.

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock

#24. Mississippi

Mississippi Capitol building.

A 2017 law made it so pharmacists can dispense naloxone through a statewide standing order to anyone who requests it. The Stand Up Mississippi initiative offers a naloxone locator, and the Narcan Now app helps people find available medication without delay.

The group’s website also links to addiction treatment programs run by the state’s Department of Mental Health.

Joe Hendrickson // Shutterstock

#25. Missouri

The Gateway Arch and riverfront in downtown St. Louis.

A statewide standing order lets pharmacists dispense naloxone without a prescription to anyone at risk or able to help someone at risk. The medication can be ordered by mail directly on the Get Missouri Naloxone webpage or at any pharmacy.

Grant funding through the Addiction Science Team at the University of Missouri-St. Louis also provides naloxone to health and fire departments, treatment and recovery centers, housing providers, and law enforcement agencies in most of the state’s counties.

Jon Bilous // Shutterstock

#26. Montana

View of Missoula from Mount Sentinel.

A statewide standing order lets pharmacists in Montana dispense naloxone to anyone without a prescription. The Montana Department of Public Health offers online resources and information on administering and distributing naloxone.

The Montana Public Health Institute works across the state to prevent overdoses and improve patients’ chances of recovery, including distributing naloxone more widely.

Canva

#27. Nebraska

Aerial view Omaha in summer.

Naloxone is dispensed free of charge in Nebraska through the Naloxone Distribution Program and from pharmacists under a statewide standing order letting anyone get the medication.

State authorities promote using the free smartphone app OpiRescue, where people can learn to recognize an opioid-induced overdose and how to reverse it using naloxone. Other treatment and crisis response resources are also available in the app.

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

#28. Nevada

Aerial view of Reno.

While there is no statewide standing order, physicians can issue standing orders to pharmacists that allow them to dispense naloxone to anyone, so long as the recipient completes some training on how to use it and how to reduce the risk of overdoses. The state publishes a wide range of data about opioid use, overuse, and overdoses.

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock

#29. New Hampshire

Aerial view of Market Square and North Church in Portsmouth.

In New Hampshire, you can get naloxone in three ways: with a prescription from a doctor, through a standing order from a doctor to a pharmacist, and at one of the nine Doorway locations.

The Doorway is a state program that assists substance abuse disorder patients and their families. New Hampshire residents can request help for mental health and addiction patients by dialing 211, where trained responders will provide information and referrals to specialists at any level of treatment.

Kamira // Shutterstock

#30. New Jersey

Aerial view Jersey City.

In January 2023, New Jersey began allowing anyone 14 years old or older to receive naloxone anonymously and at no cost at designated pharmacies across the state.

The New Jersey Department of Health dispenses naloxone and offers training on how to apply it through several public and private partnerships. It also provides naloxone rescue kits to opioid users and their friends and family, and teaches them how to prevent and react to overdoses.

Jimack // Shutterstock

#31. New Mexico

View of Santa Fe in autumn.

New Mexico pharmacists have a standing order that allows them to dispense naloxone to anyone at risk or in a position to help someone at risk without a prescription.

The New Mexico Department of Health runs a Harm Reduction Program with overdose prevention training and naloxone distribution. A flier with crucial information for first responders to an overdose is published and distributed in English and Spanish.

Thiago Leite // Shutterstock

#32. New York

Elevated view of New York City skyline.

In 2006, New York passed a law allowing nonmedical personnel to administer naloxone to people experiencing an opioid-induced overdose. Since 2022, pharmacies can dispense naloxone to anyone who asks for it under a statewide standing order.

The state’s Health Department publishes quarterly statistics on opioid overdoses statewide, whether fatal or not, to help providers, policymakers, and the public understand the problem better.

Derek Olson Photography // Shutterstock

#33. North Carolina

Asheville skyline in the fall.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists and other health care professionals to distribute naloxone to anyone who asks for it.

The state’s “Naloxone Saves” program is its effort to reduce overdoses and overdose deaths, which seeks to involve community organizations in distributing naloxone across the state, including to police departments, doctors’ offices, hospitals, urgent care centers, and other locations where people might turn when dealing with an overdose.

North Carolina publishes a dashboard, which includes county, state, and regional metrics, to monitor the problem and the effectiveness of actions to solve it.

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

#34. North Dakota

Aerial view of Grand Forks.

The state’s Good Samaritan law protects anyone who administers naloxone to someone suspected of experiencing an overdose from prosecution for possessing or using drugs.

Pharmacists may dispense naloxone to anyone at risk of an overdose or in a position to help treat an overdose, according to state law. The state’s health department promotes OpiRescue, an app with a five-step guide on responding to an opioid overdose.

photo.ua // Shutterstock

#35. Ohio

Cincinnati skyline and bridge.

Ohio state law allows physicians to issue standing orders to specific pharmacists, allowing them to dispense naloxone without a prescription to anyone at risk or who may be able to help someone at risk.

The state Department of Public Health runs a project to teach people to avoid overdoses and distribute naloxone to help treat those that occur. It’s called Project DAWN, an acronym for “deaths avoided with naloxone,” and the middle name of Leslie Dawn Cooper, a Portsmouth, Ohio, resident who died after an opioid overdose in 2009. Her hometown is the site of the state’s first naloxone distribution center.

Canva

#36. Oklahoma

Downtown Oklahoma City.

The state has a standing order that allows pharmacies to dispense naloxone to anyone without a prescription or a doctor’s visit. The medication is also available by mail and for free from vending machines along the state’s highways and even at the state Health Care Authority’s main office in Oklahoma City.

In early 2023, the state issued a warning about another drug that can be “just as deadly” as opioids and “linked to an increase in overdose deaths:” xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer sometimes known as “tranq.”

Even though xylazine is not an opioid, the state recommends administering naloxone to someone showing signs of overdose because xylazine often includes fentanyl and other opioids.

Josemaria Toscano // Shutterstock

#37. Oregon

Portland cityscape from Pittock Mansion.

Since 2016, pharmacists have been allowed to prescribe and dispense naloxone to anyone who asks for it. A state law that permits this was updated in 2017 to remove any requirement for advanced training to make getting naloxone even easier.

The state’s public health department recommends people take the training, but it clarifies that anyone who administers it—with or without training—to someone they suspect of overdosing is protected from arrest or prosecution.

A nonprofit called Max’s Mission distributes free naloxone to friends and family members of opioid users in three counties in southern Oregon.

Real Window Creative // Shutterstock

#38. Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania State Capitol building.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone who asks for it, though they are encouraged to take a free online training video about administering it.

The state Department of Aging reimburses buyers up to $75 to help cover the costs. In addition, the Pennsylvania Overdose Prevention Program offers free naloxone kits, as well as test strips to check for xylazine and fentanyl use.

Big Joe // Shutterstock

#39. Rhode Island

The Manchester Street Power Station smokestacks and Providence skyline.

Pharmacists with a standing order from a physician do not need a prescription to dispense naloxone to anyone who asks. But it’s easier than that: After completing a 10-minute interactive training—in English or Spanish—residents of Rhode Island can request free naloxone to be mailed to their homes. Several harm reduction organizations can also dispense free naloxone under request.

Canva

#40. South Carolina

Aerial view Columbia.

In 2015, South Carolina lawmakers authorized licensed pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription. That law also allows first responders to carry and administer the medication. However, the law is more restrictive than those passed in most states, as opioid users and their direct caregivers are the only ones allowed to order the medication.

Sopotnicki // Shutterstock

#41. South Dakota

Rapid City aerial view.

A statewide standing order allows at-risk people or their friends and family members to get naloxone without a prescription. The recipient must also receive training on what an overdose looks like and how to use the medication. The state Department of Health runs a program to teach public school students about the risks of using opioids.

Brian Wilson Photography // Shutterstock

#42. Tennessee

Downtown Nashville in autumn.

In 2014, Tennessee passed a “good Samaritan” civil immunity law protecting people who administer naloxone or other opioid-overdose reversal medications. A 2016 state law allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription to people at risk, and family, friends, or “close associates” of people at risk.

kintermedia // Shutterstock

#43. Texas

Aerial view of cityscape and highways.

Texas pharmacies can request a standing order from the state’s Health and Human Services Commission, which allows those pharmacies to dispense naloxone to a person at risk of an overdose or someone who could help an at-risk person.

The state links to a national map of naloxone distributors to help people find the medication in Texas or elsewhere. Texas also provides free online continuing education for pharmacists, social workers, physicians, and other health professionals who want to learn opioid response techniques, addiction recovery, and harm reduction methods.

Canva

#44. Utah

Aerial view of Salt Lake City.

Since 2016, Utah pharmacists have been able to dispense naloxone to people at risk of an overdose or those who can help at-risk people. Insurance may cover medication, but if not, the person receiving it will have to pay. Various locations throughout the state, including some libraries, fire stations, public health offices, and community centers, offer free naloxone.

Erika J Mitchell // Shutterstock

#45. Vermont

Burlington waterfront view and cityscape.

A statewide standing order allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone without a prescription. On Aug. 31, 2023, a naloxone vending machine was installed in the town of Johnson, allowing anyone to enter a numeric code and receive free naloxone. It dispensed 54 naloxone kits during its first week of operation.

The Vermont Department of Health also partners with community organizations to provide naloxone kits and related training.

Steve Heap // Shutterstock

#46. Virginia

Wide view of Alexandria along the Potomac River.

Virginia pharmacies are allowed—but not required—to dispense naloxone to anyone who asks for it under a statewide standing order.

The state offers training on responding to an overdose using naloxone, aimed at families and friends of opioid users and the users themselves. First responders, such as police officers, must receive specialized industry-specific training before carrying the medication.

kan_khampanya // Shutterstock

#47. Washington

Elevated view of Seattle Space Needle and downtown.

According to the Addictions, Drug and Alcohol Institute of the University of Washington, fentanyl caused 65% of drug-related deaths in Washington in 2022.

A statewide standing order allows anyone to get naloxone from a pharmacy, including “anyone who may witness an opioid overdose,” so long as they learn how to use it. However, access is not as simple as that order might suggest.

The Seattle Times newspaper reported in May 2023 that pharmacists at several different pharmacies “wouldn’t provide anything unless customers were patients on file and could provide a name, identification and insurance information.” State and local government agencies in Washington and around the country are about to get millions of dollars in legal settlement money to help fight the opioid crisis.

Orhan Cam // Shutterstock

#48. Washington DC

Pennsylvania Avenue and U.S. Capitol.

The D.C. Department of Behavioral Health is clear and direct: “Naloxone is available in every ward in the District, at no cost and no ID or prescription,” thanks to a local law enacted in 2016. Narcan nasal spray is available in pharmacies, by in-person delivery, and by mail by texting “LiveLongDC” to 888-811.

Canva

#49. West Virginia

Aerial view over Clarksburg.

West Virginia’s efforts to fight the opioid overdose epidemic start by acknowledging a devastating truth: West Virginia has more drug overdose deaths than any other state, according to the CDC.

A statewide standing order allows any pharmacist to dispense naloxone to anyone at risk of an overdose or in a person who could help such a person, so long as they have been given information about how to recognize an overdose and how to use the medication.

The state’s organization Next Distro provides a naloxone dispensing map, crisis support, a telephone hotline, syringe exchange services, and other assistance for those using opioids and those who care about them.

Suzanne Tucker // Shutterstock

#50. Wisconsin

Capitol building and fountain in Madison.

The state’s standing order allows pharmacies that register to dispense naloxone to anyone at risk of an overdose or who may be able to help a person experiencing an overdose.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services provides information about the benefits of naloxone and how to administer it, along with crucial data about opioid use in the state, on online dashboards that clearly show the status of the opioid crisis in Wisconsin.

C Model // Shutterstock

#51. Wyoming

City of Jackson Hole and surrounding landscape.

A 2017 Wyoming law allows pharmacists to provide the general public and law enforcement personnel with naloxone without a prescription. Though naloxone is not free when ordered at a pharmacy, the state’s Department of Health runs the Narcan for Groups program, providing agencies and organizations with free nasal sprays to distribute in the community.

Additional writing and story editing by Jeff Inglis. Additional story editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.