The timetable for a coronavirus vaccine is 18 months. Experts say that’s risky

Eighteen months might sound like a long time, but in vaccine years, it’s a blink. That’s the long end of the Trump administration’s time window for developing a coronavirus vaccine, and some leaders in the field say this is too fast — and could come at the expense of safety.

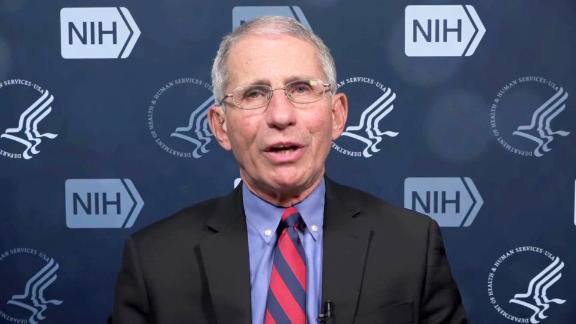

The estimated time made headlines last month, when Trump remarked at a televised Cabinet Room meeting with pharmaceutical executives that a vaccine could be ready in “three to four months.” There, in front of TV cameras, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), poured cold water on Trump’s estimate, saying it would be more like a year to a year and a half.

Ever since, that estimate of 12-18 months has become gospel, its appearance in media stories ubiquitous. But medical experts and scientists with firsthand experience developing vaccines are skeptical.

“Tony Fauci is saying a year to 18 months — I think that’s optimistic,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, a leading expert on infectious disease and vaccine development at Baylor College of Medicine. “Maybe if all the stars align, but probably longer.”

Dr. Paul Offit, the co-inventor of the successful rotavirus vaccine, put it more bluntly.

“When Dr. Fauci said 12 to 18 months, I thought that was ridiculously optimistic,” he told CNN. “And I’m sure he did, too.”

Vaccines development typically measured in years, not months

As the number of U.S. coronavirus deaths surges past 3,000, the pressure on the scientific community to find a vaccine is immense. In just a few weeks, the virus has jammed the gears of a robust economy and destroyed 3.3 million jobs. Fear is off the charts, and with that comes the pressure to find a fix yesterday.

On March 16, two weeks after the Cabinet meeting, the first federally funded trial for the novel coronavirus — officially known as SARS-CoV-2 — kicked off at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle. On Friday, it expanded to Emory University in Atlanta. Forty-five volunteers in the Seattle and Atlanta communities are participating in the first phase of the trial, which Fauci said was “launched in record speed.” (Although several vaccines are in development, only one other clinical trial is underway, in China.)

The problem is, experts say, the oft-stated timetable is ambitious at best.

“I don’t think it’s ever been done at an industrial scale in 18 months,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar focused on emerging infectious disease at the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University. “Vaccine development is usually measured in years, not months.”

Vaccine trials typically start with testing in animals before launching into a three-phase process. The first phase involves injecting the vaccine into a small group of people to assess safety and monitor their immune response. The second ramps up the number of people — often into the hundreds, and often including more members of at-risk groups — for a randomized trial. If the results are promising, the trial moves to phase-three test for efficacy and safety with thousands or tens of thousands of people, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Emily Erbelding, an infectious disease expert at NIAID — which is part of the National Institutes of Health — said the typical vaccine takes between eight and 10 years to develop. While she is careful not to contradict her boss’s timeline — although she did say “18 months would be about as fast as I think we can go” — she acknowledged that the accelerated pace will involve “not looking at all the data.”

“Because we are in a race here to beat back this epidemic and a vaccine is very important, people might be willing to take a chance on just going quickly into phase two,” Erbelding told CNN. “So the 18 months would rely upon speeding things up.”

Volunteers in each phase need to be monitored for safety, Erbelding said. “Usually, you want to follow their immune response for at least a year,” she said.

But that is not what will be happening in the current study in Seattle and Atlanta, where researchers will test animals and humans in parallel, as opposed to sequentially, according to Stat, a health news website produced by Boston Globe Media.

CNN reached out to Kaiser about the potential tradeoffs associated with a quickened timeline, but researchers at the organization were unavailable to comment.

Walt Orenstein, a professor of medicine at Emory and the former director of the US National Immunization Program, said the tradeoff is a difficult balancing act.

“If you want every ‘t’ crossed and ‘i’ dotted, how many more people will die or suffer from Covid-19?” he said. “It’s not an easy decision, it is a breakneck speed for moving things.”

Orenstein added that while there are likely lessons available from past efforts to develop vaccines against SARS and MERS, it will be tough to complete the process in 18 months, though he said it’s feasible.

“I think the reason it will be moving that fast is we have such a serious problem,” he said. “The disease is spreading like wildfire.”

In rare cases, faulty vaccine trials have proven harmful or even deadly in humans.

Mark Feinberg, president and CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, told Stat that while he recognizes the importance of animal trials, the urgency of the current public emergency makes it worth the tradeoff.

“When you hear predictions about it taking at best a year or a year and a half to have a vaccine available … there’s no way to come close to those timelines unless we take new approaches,” he told the site.

Coronavirus vaccine candidate uses new, never-before-approved technology

The vaccine under examination was created using a new, potentially revolutionary technology platform that, if successful, could indeed cut months from the development process. However, the technology — called a messenger RNA vaccine — has never been approved as a product for distribution; this would be the first.

Developed by NIAID scientists and researchers at Moderna, a Massachusetts biotech company, the experimental product — unlike most other licensed vaccines — does not use any part of the live virus. Rather, the researchers built their vaccine from the genetic information on the coronavirus provided by China. Called mRNA-1273, the vaccine uses messenger RNA (ribonucleic acid) to direct cells in the body to make proteins to prompt an immune response that prevents or fights disease.

“It’s a very elegant solution, and that’s why they could go to vaccine trials so quickly, because all they need is a sequence of the virus,” Adalja said. “They don’t have to tinker with the virus to make a vaccine candidate. They can just make a vaccine candidate with genetic sequence of the virus.”

Still, Adalja said he thinks the process will exceed 18 months, due to the possibility of clinical-trial or manufacturing issues.

At a March 26 White House briefing, Fauci stuck to his timeline, saying that he plans to expedite the process in part with a financial gamble: by encouraging companies to launch production even before the vaccine has been proven to work.

“Because once you know it works, you can’t say, ‘Great, it works, now, give me another six months to produce it,'” he said.

Fauci added that the federal government would help foot the bill.

“We’ve put hundreds of millions of dollars into companies to try and make vaccines,” he said. “I wouldn’t hesitate to do that for a moment now.”

Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, worries that the fast-tracking could cause more harm than good.

“Remember: You’re giving this vaccine, likely, to healthy people — who are not the people typically who are dying from this infection,” he said. “So you better make sure that you are holding it to a high standard of safety.”

Fauci, who did not respond to a request for comment for this story, acknowledged the importance of safety in his March 26 remarks.

“The worst possible thing you do is vaccinate somebody to prevent infection and actually make them worse,” he said.

Devastating vaccine failures

The World Health Organization estimates that vaccines save between 2 and 3 million lives a year. But vaccine history is dotted with devastating failures, in which people who got a dose fared far worse than they would have without it.

In the 1960s, a test for an RSV (human respiratory syncytial virus) vaccine failed to protect many infants from getting the disease and led to worse symptoms than usual. It was also linked to the deaths of two toddlers.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford’s administration reacted at speed to a novel swine flu outbreak, ignoring the World Health Organization’s words of caution and vowing to vaccinate “every man, woman and child in the United States.” After 45 million people were vaccinated, the flu turned out to be mild. Worse, researchers discovered that a disproportionately high number of the vaccinated — roughly 450 in all — had developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves, leading to paralysis. At least 30 people died. Upon discovery of the risk, the program was terminated in late 1976. A crush of lawsuits against the federal government followed.

In 2017, a rushed campaign — endorsed by WHO — to vaccinate nearly 1 million children for mosquito-borne dengue in the Philippines was halted for safety reasons. The Philippine government indicted 14 state officials in connection with the deaths of 10 vaccinated children, saying the program was launched “in haste.”

Keymanthri Moodley, a professor of bioethics at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, said accelerated trials increase the odds of a high-profile failure, which can bring about other unintended consequences.

“The risk of a failed vaccine to other well established immunisation programs is high,” Moodley wrote in an email to CNN. “It would fuel the agenda of the anti-vax movement and deter parents from immunising their children with other safe vaccines.”

How long did it take for rotavirus, Ebola, measles and SARS?

Historically, the timelines for bringing vaccines to bear on other pathogens show a much longer arc than 18 months.

In 2006, the vaccine co-developed by Offit was introduced for rotavirus — which caused severe diarrhea in infants — significantly blunting the disease. The entire effort spanned 26 years; the trial period took 16 years, he told CNN.

In November 2019, WHO prequalified a vaccine for Ebola, meaning health officials could start using it in at-risk countries, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where hundreds of thousands have been vaccinated. WHO said it was the fastest prequalification process it had ever conducted. The story of the vaccine’s development is complex, but all told, it took about five years to get a licensed product, said Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, in a recent TED interview.

Even back in the 1960s, when regulations were comparatively lax, it took four years for the mumps and measles vaccine to be approved, Offit said.

“The consent form was a three-by-five (inch) index card that says, ‘I allow my child to participate in a BLANK trial,’ and then you would sign it,” Offit said. “That could never happen today. And that’s the fastest it could be done.”

Occasionally a promising vaccine can languish for lack of public interest.

The SARS epidemic broke out in 2003, but it wasn’t until 2016 that a vaccine — developed by Hotez’s team in Texas — was ready for trial.

“It looked really good — it was protective, it was safe,” Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, told CNN. “But the problem was we couldn’t raise any money.”

He is looking for funding to reboot it and says the vaccine may partially protect against Covid-19, the disease caused by the current coronavirus, which is in the same viral family as SARS.

“Had investments been made previously, we potentially could have a vaccine ready to go now,” Hotez testified to Congress last month.

Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of WHO’s health emergencies programme, said testing new vaccines takes time.

“Many people are asking, ‘Well why do we have to test the vaccines? Why don’t we just make the vaccines and give them to people?’ Well the world has learned many lessons in the mass use of vaccines and there’s only one thing more dangerous than a bad virus, and that’s a bad vaccine,” Ryan said. “We have to be very, very, very careful in developing any product that we’re going to inject into potentially most of the world population.”

Sprinting a marathon on the front lines

Although just one NIH-funded trial is underway, dozens of companies and academics around the world have entered the race. Researchers are doing their best to sprint through the marathon.

Dr. David Dowling of Boston Children’s Hospital has been putting in 17-hour days — all while taking care of his two toddlers with his wife, who also works as a scientist.

“Saturdays I try and take time off,” he said. “But then on Sunday I try to do maybe a nine- or 10-hour day.”

Dowling is a faculty member in the Precision Vaccines Program that is striving to develop a “precision vaccine” for the novel coronavirus that would protect the most vulnerable group: senior citizens.

The story of how the lab, led by Dr. Ofer Levy, became involved with coronavirus offers a glimpse into the sense of urgency of some in the federal government.

Before the outbreak, the team had been working on a flu vaccine that would protect the elderly by using immune-boosting molecules called adjuvants.

When the lab, which operates in a building at Harvard Medical School, learned of the coronavirus outbreak in January, Dowling said, they sent an email to NIAID essentially asking if they could simply repurpose their flu contract for the coronavirus.

“They emailed back in like 30 seconds,” he said. “It was like, ‘Yes. Please do this as quickly as possible.'”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct David Dowling’s position in the “precision vaccine” effort. He is a faculty member in the Precision Vaccines Program, based in the division of Infectious Diseases at Boston Children’s Hospital.