20 life-changing locations that inspired movies, books, and art

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

20 life-changing locations that inspired movies, books, and art

The Beatles with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at Chaurasi Kutia.

The right combination of place, time, and frame of mind can inspire works of creativity that live on throughout history. Could Thoreau have thought up the words “a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone” were he anywhere but by Walden Pond? Would The Beatles’ “White Album” have been as transcendent if it were not fueled by the endless nights of conversation, music playing, vegetarian meals, and meditation at Chaurasi Kutia?

Stacker researched 20 locations that spurred significant changes in the lives of influential creators, telling the larger stories of artists’ humble beginnings and rebirths prompted by the places they visited or resided.

Many artists, awestruck by landscape and nature, experienced life-altering changes reverberating in their work. Some honored the flow of their creative geniuses when they encountered terrain that challenged them emotionally or physically. And others fell into places that taught them to understand different cultures and came away all the better for it.

Continue reading to learn about the history and influences of these places—and the impact these artists had on them in return.

![]()

mehdi33300 // Shutterstock

Hammamet, Tunisia: Paul Klee

Historic buildings in Hammamet with palm trees.

“Colour and I are one. I am a painter,” Swiss-born German painter Paul Klee wrote in his diary during a two-week study tour through Tunisia in 1914. By then, he had already spent three years studying drawing and painting in Munich, associating with Expressionists, and visiting a fellow artist experimenting with Cubism in Paris.

On his first trip outside of Europe, he found inspiration in Tunisia, North Africa. In the coastal town of Hammamet, the bright colors, vibrant scenes, and the heat and light of North Africa dazzled Klee. It inspired him to experiment with removing representational references from his paintings of landscapes and architecture. Instead, he translated them into abstract shapes and blocks of color, which would become his distinctive style.

“Hammamet with Its Mosque,” is one of his best-known avant-garde paintings from the time. In the years following, Klee would use the new visual language he created in Tunisia to shape his depictions of landscapes in Central Europe.

Claudio Divizia // Shutterstock

London: Jimi Hendrix

The exterior of the Handel Hendrix House museum.

From his first night in London, Seattle-born guitarist Jimi Hendrix knew his tenure there would be life-altering. That night, Hendrix wrote: “I’m in England, Dad…I met some people, and they’re going to make me a big star.” Few knew of him in the U.S., and it was in London where he found his sound and style.

Hendrix initially faced issues at a London airport for not having a work permit, but soon after, famed guitarist Eric Clapton invited him to play with Cream at the Regent Street Polytechnic. Hendrix left other “guitar players weeping,” according to singer Terry Reid.

In London, Hendrix met Roger Mayer, a sonic wave engineer for the Ministry of Defense. An inventor of musical devices, Mayer worked on the Octavia guitar effect that produced a “doubling” echo—sounds that were too “far out” for other musicians, but perfectly palatable to Hendrix, who would listen to Mozart and Handel, play jazz like Coltrane could, and read sci-fi. Together with these sonic experiments, Hendrix’s prowess produced a kaleidoscopic sound that sent shockwaves through the rock scene.

Following his premature death, Hendrix’s legacy still leaves a mark in London with the Handel Hendrix House (pictured), a museum that recreates Hendrix’s flat and that of his “neighbor,” classical musician George Frideric Handel, who lived next to the flat some 200 years prior.

Harold Cunningham // Getty Images

Lake Geneva, Switzerland: Mary Shelley

Villa Diodati and surrounding landscape in springtime near Lake Geneva.

In May 1816, 18-year-old Mary Godwin (soon-to-be Mary Shelley) only sought a vacation, and did not set out to conjure a story like “Frankenstein.” But during “the year without a summer” in 1816, frequent rainstorms and constant low temperatures from a catastrophic volcano eruption at Mount Tambora in Indonesia disrupted weather patterns across the globe and kept Shelley indoors.

To pass the time, Shelley, her future husband Percy Shelley, her stepsister Claire Clairmont, Lord Byron, and a few others spent days discussing various topics, including philosophical doctrines and principles of animation. Fueled by these discussions, Byron encouraged his companions to try writing horror stories. Shelley would use the dreary weather to reflect the environment surrounding Dr. Frankenstein, who created the famous monster that still haunts popular culture today.

Kotomiti Okuma // Shutterstock

Bruges, Belgium: Martin McDonagh

Channel and bridge in Bruges summertime.

While visiting Bruges in 2006, the British Irish playwright and director Martin McDonagh was inspired to write the screenplay for his first full-length picture, 2008’s genre-defying film and cult classic, “In Bruges.”

Bruges’s picturesque, medieval architecture and canals became a character in itself, serving as the backdrop for McDonagh to write “two different characters who might respond to Bruges in distinct ways,” he wrote in production notes for the film. His early vision became a dark comedy centering around Irish hitmen stranded in Bruges after an unsuccessful assignment.

The city, known as the “Venice of the North,” was already beloved by tourists, but after the movie, it began offering tours geared toward fans. The city has had to implement measures to avoid overtourism and “Disneyfication.”

Bettmann // Getty Images

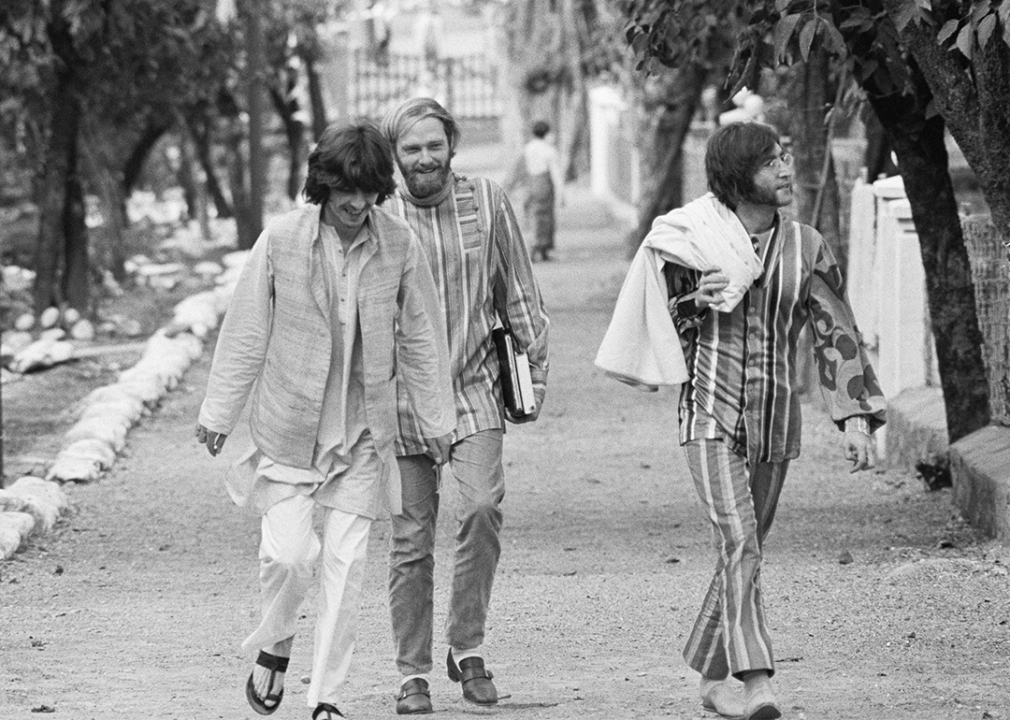

Rishikesh, India: The Beatles

George Harrison, Mike Love, and John Lennon walking and smiling together in India.

Chaurasi Kutia, an ashram at the foothills of the Himalayas, near Rishikesh in the northern state of Uttarakhand in India, was the birthplace of more than 45 Beatles songs, most of which ended up on “The White Album.”

The legendary band’s pivotal experience began in 1966 when the musical group stopped by Delhi on the way home to London after a tour in Japan and the Philippines. At the time, guitarist George Harrison was drawn to Indian music, having heard the sitar in the music his mother played and using its distinct sound in the song “Norwegian Wood.”

The brief stopover soon blossomed into a return trip to India in 1968 to stay at the ashram and learn transcendental meditation. In Bob Spitz’s book “The Beatles,” Cynthia Lennon notes, “John and George were [finally] in their element [at the ashram]. They threw themselves totally into the Maharishi’s teachings, were happy, relaxed and above all found a piece of mind that had been denied them for so long.”

McCartney was never without his guitar at the ashram, and listeners can hear the results in the “White Album.” The trip would also inspire Harrison to convert to Hinduism, becoming one of the most well-known advocates for Indian classical music.

The 18-acre ashram fell into disrepair for decades starting in the 1970s until it was restored and opened to the public as the “Beatles Ashram” in 2018, around the 50th anniversary of The Beatles’ stay.

Robert Knopes/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Chicago: The Hairy Who

The lion statues outside the Art Institute of Chicago looking out over Michigan Avenue.

The renowned Art Institute of Chicago was a breeding ground for members of the Hairy Who, six artists inspired by the Windy City. The group, all new grads of the institute, created and exhibited distinct artworks between 1966 and 1969, using vivid colors, comic book aesthetics juxtaposed with sinister images, and a good dose of satire. The work turned Chicago into an overlooked stop between New York and the West Coast into a quirky art destination.

The works of the members, including Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Jim Falconer, Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum, drew from pop art, but lacked the cool, aloof approach of Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein.

Instead, Hyperallergic writer Robert Archambeau notes, “the Chicago version of Pop isn’t cool at all: it’s sweaty, nervous, sometimes giggly or goofy.” The group’s unbridled experimentation turned into three informal Chicago exhibitions alongside appearances in San Francisco, New York, and Washington.

While the Hairy Who had a short tenure, their broader movement of Chicago Imagists is apparent in the works of Jeff Koons and Chris Ware.

Andrew Hasson // Getty Images

Mexico City: Frida Kahlo

People wait in line to visit Casa Azul in Mexico City.

Frida Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907, and her life was never easy. At 6, she contracted polio, which caused major injury to her right leg and meant a lengthy time in recovery. At 18, she was in a bus accident that killed several passengers.

The accident left her with a fractured pelvic bone, punctured abdomen and uterus, and a spine broken in three places, among other injuries. Kahlo stayed at the hospital for a month and would need a lifetime of surgeries.

She had hoped to work in the medical field, but unable to walk, she used a mirror and modified easel to paint self-portraits from bed, depicting her pain. Still, this time was transformational for her. She would later say, “Everything can have beauty, even the worst horror,” which is reflected in her surrealist paintings that capture the female form and experience, including miscarriage.

Kahlo lived with her husband, painter Diego Rivera, in the famous La Casa Azul, the same home where she was born and raised. The home—and its contents, complete with Aztec and Toltec artifacts—is now a museum.

Mike Peters // Shutterstock

Pacific Crest Trail: Cheryl Strayed

The Pacific Crest Trail winding through Cispus Basin.

At 26, Cheryl Strayed took on an ambitious challenge to trek 1,100 miles alone on the Pacific Crest Trail to work through her myriad tragedies, including losing her mother to cancer, heroin use, and divorce.

Strayed, now a bestselling author, experienced the emotional and physical catharsis she sought in the arduous hike from Mexico to Canada through the West Coast states of Washington, Oregon, and California.

In her memoir, “Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail,” she wrote, “I was amazed that what I needed to survive could be carried on my back. And, most surprising of all, that I could carry it.”

The book later became a movie starring Reese Witherspoon, tripling the number of long-distance hikers traveling the PCT and prompting the trail’s association to launch a #responsiblywild campaign to preserve the quality of the trail and promote more conscientious hiking.

La_Mar // Shutterstock

Hydra, Greece: Leonard Cohen

The town of Hydra with boats in the harbor.

Before Leonard Cohen traveled to the Greek island of Hydra in 1960, it had already been a popular spot for artists seeking seclusion, but it had eluded tourists. At 25 years old, Cohen arrived as an unknown writer, using a $2,000 grant from the Canadian Arts Council and a bequest from his grandmother to write a novel and buy a house.

The home Cohen bought had no electricity or running water, but still, it was a private place where he could work. He would later describe it to his mother: “All through the day you hear the calls of the street vendors and they are really rather musical … I get up around 7 generally and work till about noon. Early morning is coolest and therefore best, but I love the heat anyhow, especially when the Aegean Sea is 10 minutes from my door.”

While there, the coupled writers Charmian Clift and George Johnston would inspire Cohen with their lifestyle. Cohen would go on to write one of his signature songs, “Bird on a Wire,” inspired by the transformation of rustic life in Hydra in the face of technology.

In his six years there, Cohen also met his muse, Marianne Ihlen, who inspired “So Long, Marianne.” Subsequent stays in Hydra helped Cohen produce two novels, “The Favourite Game” and “Beautiful Losers.”

The island still inspires visiting artists and is home to an annual exhibition that has shown works by influential artists like Jeff Koons and Kiki Smith.

Jay Yuan // Shutterstock

Walden Pond, Massachusetts: Henry David Thoreau

A sign with Thoreau’s description of living by the shores of Walden Pond.

On the woodlands owned by his friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson, philosopher and writer Henry David Thoreau built his well-known cabin. He sought solitude and simplicity in the cabin on the shore of Walden Pond between 1845 and 1847. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,” Emerson wrote in “Walden.”

After living in the cabin for two years, two months, and two days, Thoreau emerged from his refuge to write “Walden,” which took him nine years. The book sold 1,744 copies in its first year, but its influence has lasted generations. Thoreau’s views on how industrialization and war changed the world at large resonated with the youth of the equally turbulent 1960s and ’70s and even today.

A replica of Thoreau’s cabin now stands today near Walden Pond. About 80% of Walden Woods is under the protection of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

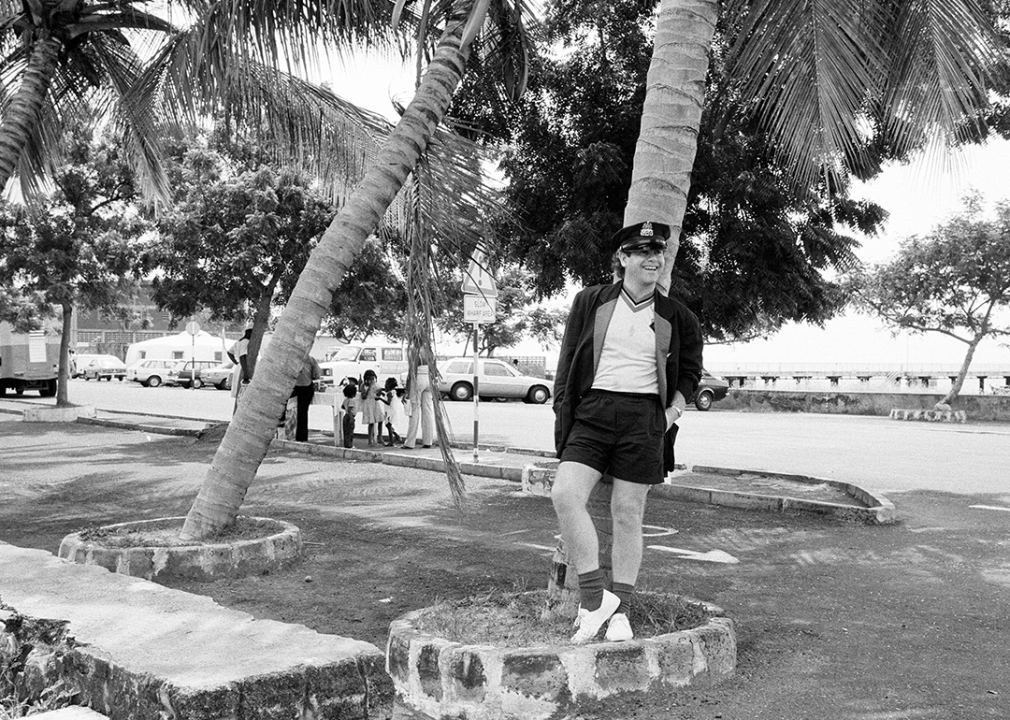

Carl Bruin/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Montserrat, Caribbean: Sir George Martin

Elton John standing under a palm tree on Montserrat.

This island of only 40 square miles in the Caribbean inspired Sir George Martin, The Beatles’ producer, to build a sister recording studio to its London counterpart called AIR Montserrat, in the shadow of the Soufrière Hills volcano in 1979.

Over the next 10 years, the once-idyllic island became the setting for rock and pop album recordings from artists like Elton John, the Rolling Stones, Duran Duran, the Police, and Black Sabbath, who would all move in to record in the state-of-the-art facilities, showcased in the documentary, “Under the Volcano.”

Verdine White, founding member of the band Earth, Wind & Fire, recalls AIR fondly, saying: “I’m from Chicago. We don’t do volcanoes,” but “AIR Monserrat touched our spirit in a different way. It touched our spirit. There was no clock.”

The studio operated until 1989, when Hurricane Hugo destroyed 90% of the island structures. While the recording studio remains ruined, the memorable hits it has produced continue to live on.

Tony Vaccaro // Getty Images

Various locations, New Mexico: Georgia O’Keefe

Georgia O’Keeffe stands at an easel with a large painting outdoors.

Today, Georgia O’Keefe’s modernist work is synonymous with the red and orange landscapes of Taos, New Mexico. It gradually became her home over two decades, when she’d escape New York City during the summers.

Her paintings, which made her the first woman to earn respect in the New York City art scene in the 1920s, featured a series of skyscrapers and cityscapes, but the starkness of New Mexico changed O’Keefe’s approach to painting. Rather than capturing these city scenes, she trained her eyes on the warm landscapes, white cliffs, and dried bones of the desert in New Mexico.

At 47, she painted one of her most notable works, “Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills,” which prominently features a skull of a ram’s head and a flower that symbolized her rebirth as an artist. She would later describe New Mexico this way, “The sky is different, the wind is different. I shouldn’t say too much about it because other people may be interested and I don’t want them interested.”

F11photo // Shutterstock

Antebellum South: Kara Walker

Oak Alley Plantation in Louisiana.

California-born Kara Walker became the second-youngest recipient of the MacArthur Foundation’s “genius” grant at 28, three years after taking the art world by storm: Her panoramic cut-paper silhouettes in black incorporated elements of the South with images of slavery and racism against starkly white walls.

Walker turned this artistic technique, most often reserved for family portraits, to showcase images of tense scenes that forced the viewer to reflect upon the tortured history of the Antebellum South.

Since then, Walker’s work has evolved into large sculptures like “A Subtlely: or the Marvelous Sugar Baby,” a monumental sphinx-shaped statue wearing an Aunt Jemima kerchief and earrings that pays homage to unpaid and overworked cane field workers.

Aeypix // Shutterstock

Mount Fuji, Japan: Katsushika Hokusai

Mount Fuji at Lake Kawaguchiko with cherry blossoms framing the view.

Mount Fuji (or Fujisan) is the tallest mountain in Japan, a site for pilgrimages, and an active volcano. Over 200,000 hikers make the trek to this revered site every year.

Art lovers might know it from the work of Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblocked prints that captured its peak from more than 36 views—but his most emblematic version was of “The Great Wave.” His 1830-32 print of Fujisan appears small compared to the dramatic, finger-like waves cresting over three fishing boats.

Hokusai was over 70 years old when he began the series, depicting the mountain, which symbolizes longevity, across all seasons, potentially reflecting his wish to live to 110 years old.

Ryan DeBerardinis // Shutterstock

New York City: Maira Kalman

People walk across 3rd Avenue in Manhattan during rush hour traffic.

Many artists cite New York City as a life-changing location that inspired their work. However, Israel-born Maira Kalman may take the cake for viewing the city and painting a reflection of its kaleidoscopic characters.

Her colorful drawings, often paired with loopy, whimsical handwriting, frequent the covers of New Yorker magazines, Broadway show curtains—including in David Byrne’s “American Utopia.” Her art is inspired by observations of the people she encounters through her walks through Central Park or visits to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Frick Collection.

Reflecting on nearly a lifetime living in New York City, Kalman told Magenta, “Superficially, of course, it’s more gentrified, but it hasn’t been whitewashed into only rich people who can afford expensive things. It’s a staggering ethnic mix. In the fabric of people and madness and intricacy, it hasn’t changed at all. It just still is incredible. Also, I really don’t like generalities in terms of what the city is like.”

Pablo Blazquez Dominguez // Getty Images

Pamplona, Spain: Ernest Hemingway

Crowds fill the streets, watching the San Fermin Festival in Pamplona.

Ernest Hemingway’s travels took him all over the world, and his works of fiction, known for its succinct, direct style, later propelled him to win prizes like the Pulitzer and Nobel Prize in Literature.

However, his first novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” featured Pamplona, Spain, a city he would grow to adore. Pamplona inspired Hemingway to write of bohemians enjoying the San Fermin Festival’s running-of-the-bulls event.

Author Gertrude Stein first suggested Hemingway visit Pamplona during its carnival season, and he visited nine times beginning in 1923. But it was his 1926 novel “The Sun Also Rises” that captured the heart of a “lost generation” looking to find themselves in excess and thrills like watching the dramatic festivities in San Fermin.

The city would later become overrun by tourists, partially due to his influence. Hemingway’s last visit to the city in 1959 was perhaps the most unhappy with fascist rulers at his helm who banned his books.

Alex Segre/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Paris: Meret Oppenheim

Waiter at the busy Cafe de Flore in Saint-Germain-des-Pres.

Méret Oppenheim’s bantering with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at the Café de Flore inspired her infamous and iconic piece, “Object (or Luncheon in Fur),” which was exhibited at the first surrealist exhibition of objects at Charles Ratton Gallery in Paris and then later at the MoMA. The piece would become the first object made by a woman acquired by the vaunted art museum, earning Oppenheim the moniker “First Lady of MoMA.”

Paris’ cafes and French fashion undeniably inspired Oppenheim’s piece. While at the cafe, Picasso jokingly said that anything could be covered in fur, which prompted Oppenheim to reply, “Even this plate and this cup here.” When her tea was cooling, she jokingly asked the waiter for more fur for her cup—rousing her to create a fur-covered piece that would both mark her as an “artist who works in fur” and cement her place in surrealist art.

Ted Soqui/Corbis via Getty Images

Bali, Indonesia: Elizabeth Gilbert

The bridge featured in the film “Eat Pray Love.”

Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2016 memoir, “Eat, Pray, Love,” spent more than 170 weeks on the “New York Times” bestseller list and later became a movie featuring Julia Roberts as the author. The story follows Gilbert’s soul-seeking journey that spanned Italy (to eat), India (to pray), and Bali (to love).

Gilbert set out on her yearlong travels to heal following a divorce and wrote about the guidance she found from a spiritual healer in the town of Ubud, which sent her on her journey. In the book, Gilbert outlines how Ketut Liyer predicted the author’s return to Bali. She said in her book: “The Balinese don’t wait and see ‘how things go.’ That would be terrifying. They organize how things go, in order to keep things from falling apart.”

Gilbert’s influence on Indonesia was so profound with spiritual seekers that the Minister of Culture and Tourism issued a call to train more hotel staff in Ubud in yoga and meditative practice.

trekandshoot // Shutterstock

Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles: Joni Mitchell, et al.

Aerial view of steep hillside homes near Laurel Canyon Boulevard.

Joni Mitchell summarized the notoriety of Laurel Canyon, a neighborhood behind Sunset Boulevard:

“When I first came out to L.A. [in 1968], my friend [photographer] Joel Bernstein found an old book in a flea market that said: ‘Ask anyone in America where the craziest people live and they’ll tell you California. Ask anyone in California where the craziest people live and they’ll say Los Angeles. Ask anyone in Los Angeles where the craziest people live and they’ll tell you Hollywood. Ask anyone in Hollywood where the craziest people live and they’ll say Laurel Canyon. And ask anyone in Laurel Canyon where the craziest people live and they’ll say Lookout Mountain.’ So I bought a house on Lookout Mountain.”

Vanity Fair’s Lisa Robinson contends that the canyon was the hotbed for “the most melodic, atmospheric, and subtly political American popular music” of the mid-1960s to the early 1970s.

Much of the music would be considered formative to today’s Americana genre. Its residents, including Bonnie Raitt, Carole King, the Eagles, Crosby, Stills, and Nash, socialized and collaborated heavily. At Laurel Canyon, these artists found a refuge among likeminded souls who felt at home in the neighborhood’s winding roads and countercultural values.

Sergey Golotvin // Shutterstock

Santiago de Compostela, Spain: Paulo Coelho

A view from the distance of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

Following a pilgrimage from the French border to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the now-acclaimed Brazilian writer of “The Alchemist” Paulo Coelho wrote his first book at 38, aptly titled, “The Pilgrimage.”

After the trek and writing his first book, Coelho reflected on why it had taken him so long to fulfill his dream of writing, which sparked the inspiration for “The Alchemist.” The story tells the tale of a man named Santiago who journeys to Africa to pursue his dream of seeking treasure—only to find it back home where he first dreamed of the treasure.

Coelho’s books were responsible for an incredible increase in pilgrimages, from an estimated 450 a year to 100,000 in 2007, as Newsweek noted. “This road to Santiago was sleeping these past 400 years,” Phil Cousineau, author of “The Art of Pilgrimage,” told Newsweek. ”And then, all of a sudden, it awoke, spontaneously.”

“The Alchemist” has sold more than 2 million copies worldwide.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.