4 milestones in workers’ compensation law in US history

China Photos // Getty Images

4 milestones in workers’ compensation law in US history

Workers weld on the roof of a building

The concept of workers’ comp dates back to ancient Sumer (modern-day Iraq). Back then, the law of the city-state Ur provided workers with monetary compensation for specific injuries to their body parts, including fractures.

Since that time, the landscape of work and workers’ compensation has undergone many changes. For a long time, highly restrictive standards that evolved out of English common law made it difficult for workers to hold employers at fault for on-the-job injuries, protecting employers from having to compensate workers for injuries that occurred in the workplace. Some cases—such as Martin v. the Wabash Railroad and Farwell v. the Boston & Worcester Railroad Corp.—established some of these defenses in the U.S.

Federal and state governments have since enacted a variety of workers’ compensation laws to better protect employees’ rights. More than 35 years passed between the first state to legislate workers’ compensation laws and the last state to do so. Today, even remote workers have workers’ compensation protections.

Simply Business compiled some of the landmark cases and legislation in U.S. workers’ compensation history from a collection of expert sources. Keep reading to learn more about major milestones in American workers’ compensation law.

![]()

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group // Getty Images

Martin v. the Wabash Railroad

Color photomechanical print of Wabash Avenue, North from Adams Street, Chicago

In the Martin v. the Wabash Railroad case, a freight conductor was working on his train when he fell from it. Even though inspectors blamed a loose handrail for the fall, the freight conductor didn’t receive compensation for his injuries—because one of his job duties was doing faulty equipment inspections on the trains.

The lack of compensation, in this case, came down to what’s referred to as “contributory negligence,” which asserts that, if there was even the slightest responsibility for the injury on the part of the employee, then the employer wasn’t at fault. The Martin v. the Wabash Railroad case helped establish contributory negligence in the U.S.

Smith Collection/Gado // Getty Images

Farwell v. the Boston & Worcester Railroad Corp.

An elevated view of of South Station, Boston, Massachusetts, 1905

The Farwell v. the Boston & Worcester Railroad Corp. case established the “fellow servant” rule in U.S. law, which allows employers to escape liability if their employee’s injury was caused by the negligence of another employee.

This case came about because of a severe injury that Nicholas Farwell, who worked for the Boston & Worcester Railroad Corp. as an engineer, experienced due to a mistake made by a switch operator who also worked for the company. Due to the error, Farwell was thrown out of a railway car as it derailed and his arm was tragically crushed beneath the train wheels.

According to the court, Farwell’s employer was found not liable for the injuries he suffered as a result of the negligent acts of their fellow employee. As a rule, the court held that employers should generally not be held responsible for injuries to an employee caused by a “fellow servant” who is also under their employment—unless the employer was negligent in the selection of the fellow employee.

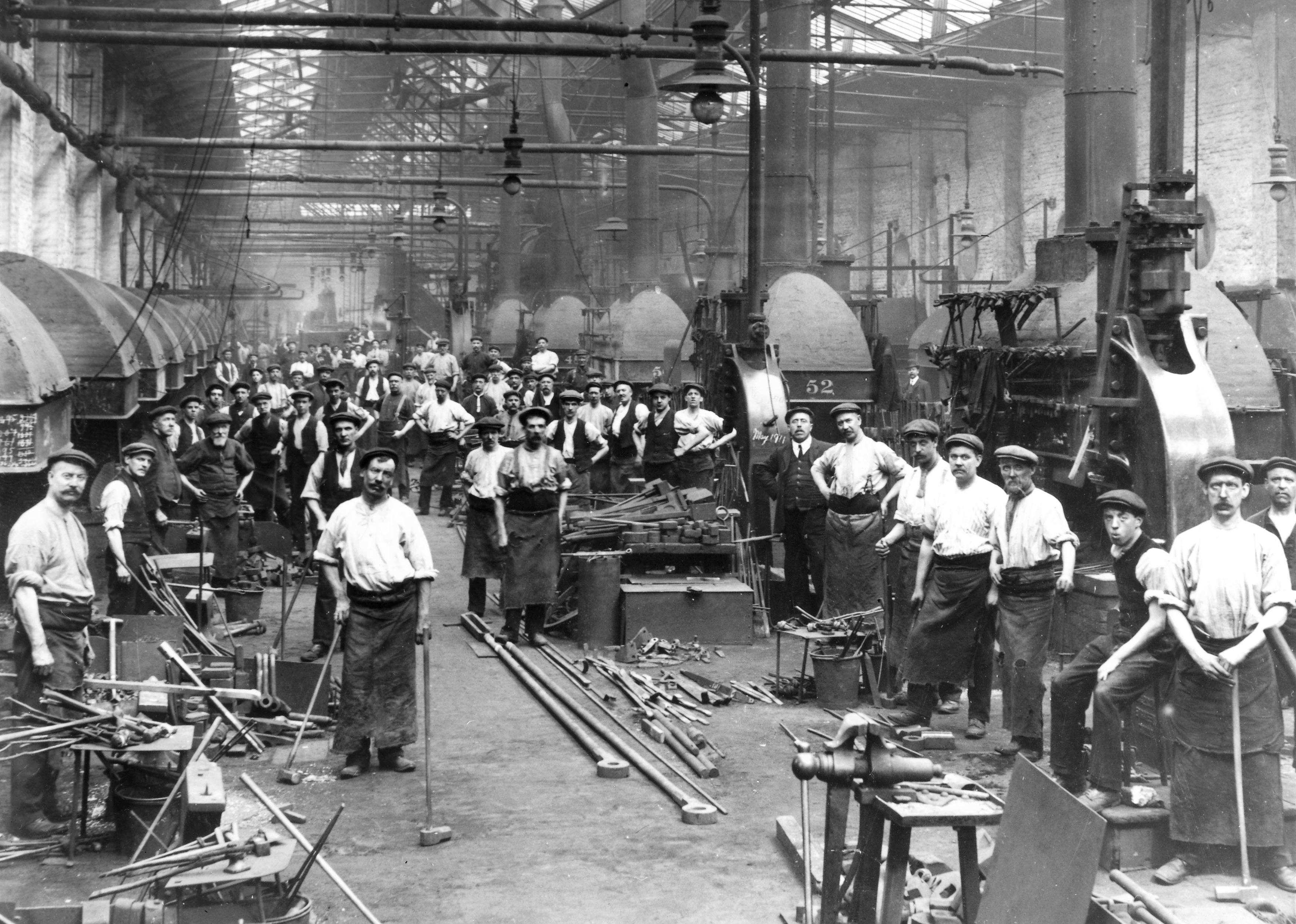

Science & Society Picture Library // Getty Images

Federal Employers Liability Act

Railway workers in the blacksmiths

As sentiment regarding workers’ compensation changed on both sides of the Atlantic, pro-labor thinking eventually made its way into the U.S.—with Congress passing the Federal Employers’ Liability Acts of 1906 and 1908, which softened the contributory negligence doctrine, establishing a version of workers’ compensation for railroad workers. Due to growing public awareness of the hazards railroad workers experienced during the massive expansion of railroads across the country from 1889 to 1920, Congress enacted this legal change to reduce the number of injuries and deaths caused by accidents on interstate railroads.

To receive benefits under the law, a worker must be able to prove that the railroad company or one of its agents was legally negligent, at least partially, or that a faulty piece of equipment was responsible for causing the injury.

It’s important to note that even though the protection under the law, commonly referred to simply as FELA, provides railroad workers is comparable to workers’ compensation insurance provided within other industries, it is—unlike workers’ compensation—a fault-based system. If an employee wishes to receive benefits under this law, they must go through the process of proving fault. Then, if the employee is found to be less than 100% at fault, they have the right to sue for damages in a federal or state court—a right that workers’ compensation claimants do not have.

Universal History Archive // Getty Images

State-level laws

Workers walk along a dock in Superior, Wisconsin

After the passing of FELA at the federal level, states began to enact workers’ compensation laws that would apply to employees more generally—not just to railroad workers.

Although several states attempted to enact workers’ compensation laws around the same time that FELA was passed, these laws were struck down as unconstitutional when challenged in court. It wasn’t until Wisconsin passed the Workmen’s Compensation Act in 1911 that a workers’ compensation law was found to be constitutional. This act puts into place a “no-fault” system so that a worker would no longer be obligated to prove that there was negligence on the employer’s part to receive benefits. It also eliminated the three common law defenses that employers could use that were very difficult to overcome in court—remember the “fellow servant” rule and the contributory negligence principle from earlier in the article?

The Wisconsin lawmakers’ intent was that employers would be required to accurately and promptly compensate their workers for any injuries suffered while on the job, regardless of whether the employer or a co-worker was at fault. In return, the 1911 law limited how much money Wisconsin workers could recover. This made it so that workers were generally only entitled to recover lost wages, medical treatment costs, specific disability payments, and vocational rehabilitation or retraining payments.

In the same year Wisconsin passed its workers’ compensation law, nine other states passed their own workers’ compensation law. By the end of the 1910s, 36 other states had passed workers’ compensation regulations. Mississippi was the last state to pass its own workers’ compensation laws, in 1948.

This story originally appeared on Simply Business and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.