'Hurricane season from hell' could drive up home insurance costs on vulnerable US coastline

Felix Mizioznikov // Shutterstock

‘Hurricane season from hell’ could drive up home insurance costs on vulnerable US coastline

Aerial image of homes destroyed in the Florida Keys after Hurricane Irma.

Weather experts have warned that the 2024 hurricane season could be especially destructive. The U.S. could see five to eight hurricane impacts, three to five of those major, according to the forecasting service WeatherBELL Analytics.

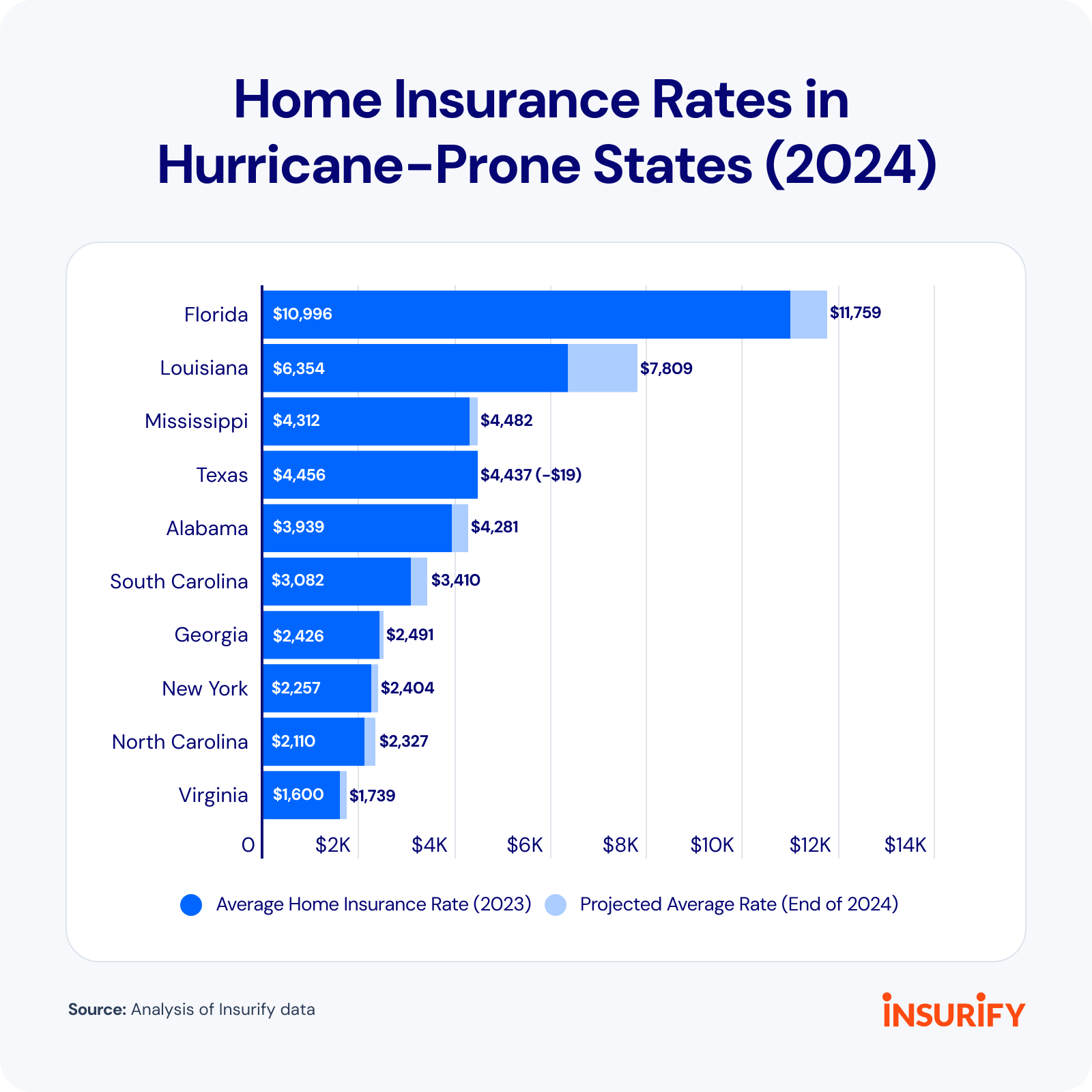

Homeowners in some hurricane-prone states already face the highest home insurance rates in the country. Astronomical costs from hurricane damage claims contribute to Florida’s average annual home insurance rate of nearly $11,000. Louisiana, the second-most expensive state, has an average annual rate of $6,354, according to Insurify data.

Resilient construction mitigates hurricane damage, but many homeowners are unprepared for a severe season. Less than 35% of Americans live in areas with modern, updated building codes, according to Rating the States 2024, an Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) report.

Homeowners can’t control the weather, but they can take practical steps to reduce insurance costs and prevent wind damage to their homes.

Quick Facts

- The average annual home insurance rate in Atlantic and Gulf Coast states is $2,994 — 26% higher than the 2023 national average of $2,377.

- Five of the 10 most expensive states for home insurance — Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama — are susceptible to damages from a severe 2024 hurricane season, which could cause further rate increases.

- Florida residents, who inhabit the most hurricane-prone state in the country, paid an average of $10,996 annually for home insurance in 2023. They might end up paying $11,759 — 7% more — at the end of 2024, according to Insurify’s projections.

- Mortgage delinquency rates in Louisiana’s Houma metro area jumped from 1% to over 7% in the month after Hurricane Ida hit, according to CoreLogic.

- The 2022 hurricane season was the second costliest on record, with Hurricane Ian causing $65 billion in insured losses, according to reinsurance provider Swiss Re.

- Florida’s modern building code prevented an estimated $1 billion to $3 billion in damages to single-family homes alone in areas affected by Hurricane Ian, according to the IBHS.

![]()

Insurify

Louisiana, South Carolina, and Maine can expect double-digit insurance rate hikes

Bar graph showing home insurance rates in hurricane prone areas.

The U.S. could see a “hurricane season from hell” in 2024, according to WeatherBELL. The Atlantic basin will become an ideal environment for hurricane formation as El Niño, a period of warming ocean surface temperatures, reverses into La Niña, a period of cooling.

Accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), which measures wind energy and the overall activity of tropical cyclones, could reach two to three times the average on the Southeast coast of the United States. The odds of La Niña developing by June to August 2024 are 60%, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“If there’s a surge in the number and intensity of hurricanes, insurance companies would face higher payouts for property damage, business interruption, and other related claims,” says Jacob Gee, an insurance agent and quality assurance specialist. “This would likely lead insurers to reassess their risk models and adjust insurance rates accordingly.”

Post-hurricane rate adjustments could mean steep hikes for homeowners affected by a hurricane, but they wouldn’t see premium increases immediately, says Gee.

First, insurance companies would collect data on the damages. Then, insurers would assess the data, factor it into risk models, and propose new rates to ensure they meet state regulatory standards. If regulators approve rate hikes, insurers notify policyholders in their renewal documents.

Several coastal states, including Louisiana, South Carolina, and Maine, could see double-digit home insurance rate hikes in 2024, according to projections by Insurify’s data science team. Louisiana’s home insurance costs may increase by as much as 23%.

Post-disaster insurance fraud also drives rate increases, especially in Florida, says Joseph Brenckle, director of public affairs with the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB).

“Unfortunately, disreputable contractors often swoop in after a catastrophic event, preying on desperation with high-pressure tactics and promises of quick fixes,” says Brenckle. “In 2023, U.S. insurers paid more than $92 billion in catastrophe losses, with upward of 10%, or $9.2 billion, lost to post-disaster fraud. This can add hundreds of dollars to a homeowner’s annual premium.”

Roof replacement schemes have contributed “enormously” to net underwriting losses for Florida insurers, according to Sean Kevelighan, CEO of the Insurance Information Institute.

Reinsurance rates jumped by 50% in response to natural catastrophes

Insurance companies have insurance too. Reinsurance provides coverage to insurers when they need to distribute some of the costs of damage from catastrophic events. Home insurers often turn to reinsurance after destructive hurricanes.

“The increased demand for reinsurance would likely lead to higher costs for insurance companies. Reinsurers would need to adjust their pricing models to account for the elevated risk and potential for more significant losses,” says Gee.

Catastrophe reinsurance rates increased by up to 50% upon renewal on Jan. 1, 2024, for policies hit by natural disasters, according to a Gallagher Re report. Reinsurance rate increases for insurers are often passed down to policyholders through higher home insurance premiums.

Building codes, quite literally, are make-or-break

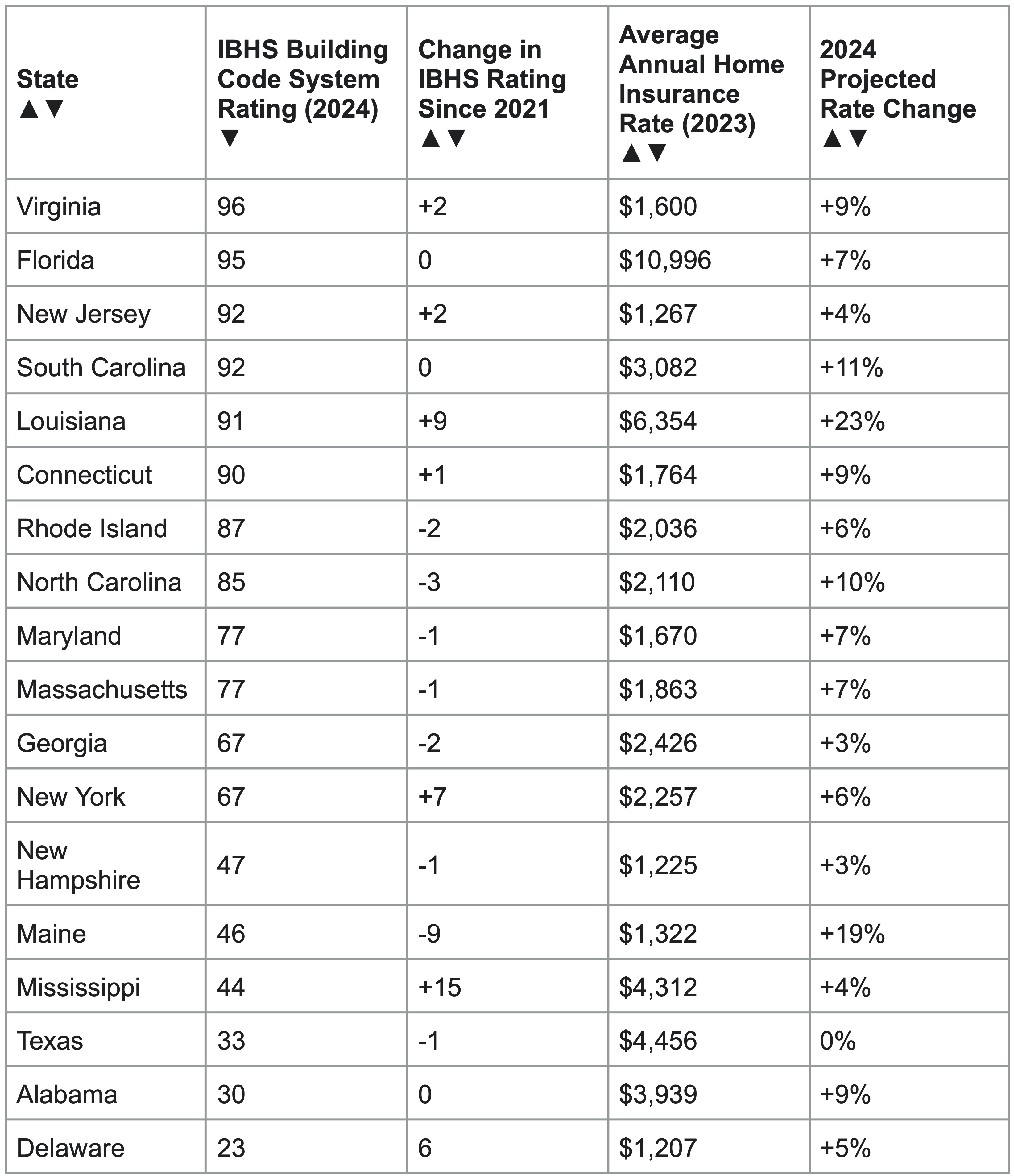

When enforced, building codes save homeowners from weather-related damages totaling billions of dollars, the IBHS Rating the States 2024 report found. The report evaluates 18 states across the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and rates them on a 0–100-point scale based on building code adoption, implementation, and enforcement systems toward mitigating windstorm damage.

After Hurricane Ian, the IBHS analyzed 455 single-family homes and 57 multifamily structures built under the modern Florida Building Code (FBC). None of the FBC-built homes had structural damage. The FBC prevented an estimated $1 billion to $3 billion in damages to single-family homes.

Florida enacted the FBC in 2002, which means a higher proportion of homes and buildings are up to a strong modern standard compared to states like Louisiana, which updated its building codes in 2023. These states might not fare as well if hit by a storm that’s equivalent to Hurricane Ian, says Dr. Anne Cope, chief engineer for the IBHS.

“Building codes are a marathon game, not a sprint,” says Cope. “Enacting a building code today is not going to change the buildings that are on my street right now. But it will change the way they’re built in new neighborhoods. It will change the way that we re-roof them. … But it’s a long-term effort.”

Getting stakeholders on board for that long-term effort is challenging. Resilient construction that adheres to modern building codes costs about $2 more per square foot — a cost developers and homebuyers often find difficult to stomach.

“It does add to the initial purchase price of the structure, but it reduces the lifecycle cost,” says Cope. “So, by paying just a little bit more up front, you get a more durable structure, and the maintenance and ownership costs will [be lower] over time.”

Resilient building standards are still a “tough sell,” says Cope, despite National Institute of Building Sciences data showing that adopting the latest building codes saves $11 in damages per $1 invested.

Insurify

Poor building codes leave hurricane-prone states vulnerable

Table showing each state and their IBHS ratings, insurance rate, and projected changes.

“Most people presume that here in the United States — across all of the United States — we probably have building safety standards. But they would be wrong,” says Cope.

Many states, including Delaware, Alabama, and Texas, develop building codes on a local level, which means millions of homeowners live in areas with outdated regulations, if any. Unsurprisingly, Delaware, Alabama, and Texas have the lowest ratings in the IBHS report.

IBHS created FORTIFIED, a voluntary beyond-code construction and re-roofing method, in response to the lack of standardized building codes. The I-Codes, developed by the International Code Council (ICC), offer similar protection to homeowners.

“We have the information; we have the knowledge,” says Cope. “If people would simply use the model building codes that we have, we would be in a good spot.”

Louisiana, one of the most improved states according to the report, now uniformly enforces the ICC’s latest International Residential Code (IRC). The state saw five landfalling hurricanes between 2020 and 2021, the latest being Hurricane Ida. The resulting damages and strain on the private insurance market may have spurred Louisiana to update building codes.

Building code adoption is often reactionary, says Cope. “My home state of Florida was walloped by Hurricane Andrew in 1992. … Florida doubled down and said, ‘We will not allow this type of thing to happen to us again.’ It took 10 years because the good, modern Florida Building Code came out in 2002 … but Hurricane Andrew was a game-changer, watershed moment.”

Mobile County and Baldwin County in Alabama had a different watershed moment — Hurricane Katrina, which displaced 1.5 million residents across Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. “Those two counties have adopted most of the provisions of FORTIFIED [building standards], even though Alabama doesn’t have a statewide code,” says Cope.

States don’t always move toward stronger building codes. North Carolina, which enforces the out-of-date 2015 IRC, put a moratorium on new building codes until 2031. Code updates include information about recently developed building materials and their performance against natural catastrophes.

Hurricanes drive mortgage delinquencies

Homeowners already feel strained, and an active 2024 hurricane season could displace those living on the financial edge. Costly wind damage is unaffordable to fix for some homeowners, especially without insurance, and standard homeowners insurance policies don’t cover flood damage.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of homeowners Insurify surveyed don’t have flood insurance, and among that group, 13% thought their regular home insurance policies covered flood damages.

Thirty percent of homeowners in a 2024 Insurify survey said they can’t afford their current mortgage interest rate now or in the future. Among that group, about 21% said they can afford it now but not for long, nearly 9% are tapping into savings until they refinance, and less than 1% say they can’t afford their home any longer.

Hurricanes often drive residents out of their homes permanently. Mortgage delinquency rates in Louisiana’s Houma metro area increased from 1% to over 7% in the month following Hurricane Ida, according to CoreLogic.

Yet homes constructed under modern building codes reduced the jump in mortgage delinquencies following major hurricanes by nearly 50%, a joint study by CoreLogic and IBHS found.

Weathering the storm

The more active hurricane season forecasted for 2024 reflects a larger pattern. Extreme weather events will continue to increase due to climate change, the NOAA predicts. Still, homeowners can take proactive steps to mitigate damage to their homes and lower their insurance premiums.

Gee recommends homeowners make resilient choices when it’s time to renovate or remodel. “Installing storm shutters, reinforcing roof attachments, and upgrading to impact-resistant windows and doors are a few ways to mitigate damage, and many insurance carriers provide discounts, as this reduces the chance of loss on the insured’s property.”

Cope echoed this sentiment, recommending homeowners look up their local building codes on Inspect to Protect and refer to the IBHS FORTIFIED standards if an up-to-date code isn’t in place. Local grants, like the Louisiana Fortifiy Homes program, could cover some of the cost by providing financial assistance for FORTIFIED Roof upgrades.

Improvements unrelated to storms can further lower insurance premiums, says Gee. “Examples include discounts for installing security systems, smoke detectors, fire alarms, and other safety features that can reduce the risk of property damage and insurance claims.” Bundling home and auto insurance or raising deductibles can reduce premiums even more.

Cope believes modern building codes can mitigate damage and reduce pressure on the insurance market as the U.S. experiences more frequent and severe weather events.

“Combining the sheer number of [weather] events with inflation on materials and supply chain difficulties, we’re seeing ripples in the insurance market that we haven’t seen before occurring in multiple states,” says Cope. “When these pressures hit us, the only thing that can alleviate that is more resilient construction.”

Methodology

Insurify data scientists determined average home insurance rates by combining real-time quotes from partner carriers and aggregated rate filings from Quadrant Information Services.

Rates represent the average annual cost of an HO-3 insurance policy for homeowners with good credit and no claims within the past five years. The policy covers a single-family frame house. Coverage limits are $300,000 dwelling, $300,000 liability, $25,000 personal property, $30,000 loss of use, and a $1,000 deductible.

Statewide costs reflect the average rate for homeowners across ZIP codes in the 10 largest cities. Insurify data scientists analyzed insurance company rate increases implemented throughout the second half of 2023 and into early 2024 to project end-of-2024 rates.

This story was produced by Insurify and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.