Texas health advocates advise El Paso abortion seekers to protect their data privacy, safety

The Heartbeat Act. The abortion bounty law. The “sue thy neighbor” law.

Texas Senate Bill 8 goes by many names, but abortion rights advocates warn one of the main takeaways is that people must be careful with their reproductive health information – now more than ever.

SB 8 went into effect on Sept. 1, authorizing the public to sue anyone who performs an illegal abortion. The law also targets anyone who helps, or intends to help, someone get an illegal abortion. Each accuser can sue for at least $10,000 in statutory damages per abortion, plus court costs and attorneys’ fees.

Texas has a trigger law that bans abortion in almost all cases, including rape and incest. The law was prepared and passed to go into effect following the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark decision that for nearly 50 years protected a person’s choice to not continue their pregnancy. The trigger law will be enacted after the court’s judgment, which will be issued separately from its June 24 opinion.

Abortion laws in Texas have created a bounty system that incenticizes anti-abortion activists to monitor people’s behavior, said Rachel, board president of West Fund, a nonprofit abortion fund based in El Paso. (Rachel asked that their last name not be published due to safety concerns.)

While people in El Paso still have several ways to access safe abortions – from international telemedicine and medical clinics in New Mexico – the ambiguity of SB 8 can put some actions in a legal gray area.

That opens up the possibility of criminalization and lawsuits, and people’s personal data can be used against them.

Navigating abortion funds, underground auntie networks

In the immediate aftermath of Roe v. Wade’s overturn, some reproductive rights supporters went on social media to offer aid, such as driving people to an out-of-state abortion clinic or offering a spare bedroom.

People should be discerning when responding to offers of help from strangers on the internet, Rachel warned.

“People can have the best intentions, but be completely unaware of the landscape and risks while mitigating harm,” Rachel said. “People are asking very vulnerable people to put trust in complete strangers on the internet. … This can be used to harm people seeking care. You don’t know who’s going to be on the other side of this phone call or this room being offered.”

While many abortions funds in Texas have paused abortion-related services over the summer to get legal guidance on their operations, they are still accepting donations and running other services. The nonprofit organizations help pay for abortions – including travel, lodging and the procedure itself – for those who cannot afford it.

Along with West Fund, nonprofits in Texas include Lilith Fund, the state’s oldest abortion fund; The Afiya Center, which supports Black women and girls; and Jane’s Due Process, which helps Texans under 18 get birth control and find the nearest abortion clinic.

There are also abortion funds based in New Mexico, where the procedure is legal. There were only six abortion clinics in New Mexico at the time of Roe v. Wade’s overturn, only three of which perform surgical abortions, and the clinics are fielding a high volume of calls from Texas.

Abortion funds in New Mexico include Mariposa Fund in Albuquerque, which supports undocumented people trying to obtain reproductive health services. Others are Indigenous People Rising, which supports Native Americans, and New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, a fund supported by clergy and religious leaders across the state.

Underground abortion networks, known as auntie networks, are also connecting people to abortion services. But Rachel and other abortion fund leaders urge volunteers or donors to tap into existing abortion funds that vet their volunteers. Some of these established groups have already spent years building both infrastructure and trust in their communities, Rachel said.

A Reddit group with more than 115,000 members, r/auntienetwork, announced on June 29 it was temporarily suspending volunteer services because of safety concerns.

“We don't have budget, means, or staff to background check everyone who volunteers, and although 90 percent of the applications we see are great people...it's a gamble no longer worth taking,” reads a moderator’s post.

Pregnancy centers don’t fall under medical privacy law

Not all groups intend to share options or resources for legal abortions.

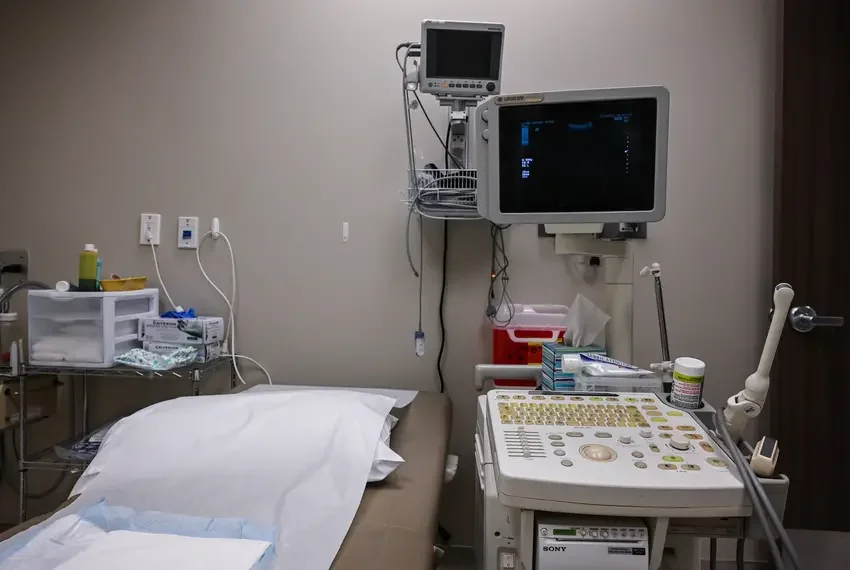

Searching for abortion and women’s health clinics online will likely bring up crisis pregnancy centers, most of which are not licensed as health care faciities. Crisis pregnancy centers have a history of trying to deter people from terminating their pregnancy and outnumber abortion clinics.

El Paso has several crisis pregnancy centers, including Pregnancy & Fatherhood Solutions, Westside Pregnancy Center and Guiding Star El Paso, which is located down the street from Planned Parenthood. These nonprofits provide services such as pregnancy tests and sonograms, as well as post-birth resources, from diapers to infant caretaking classes.

People who are seeking abortion services are not obligated to share their pregnancy outcomes with these centers.

Pregnancy centers that are not licensed health care providers do not fall under HIPAA, the federal privacy law that protects a patient’s information from being disclosed without the patient’s consent or knowledge.

HIPAA only applies to health care providers who engage in electronic transactions, such as billing services. Many pregnancy centers, which may disguise themselves as abortion clinics, provide services for free.

There are no abortion clinics in El Paso. But a recent Google search for abortion clinics in El Paso brought up an advertisement for ‘Women’s Clinic in El Paso.’ When clicked on, it leads to the website of Pregnancy & Fatherhood Solutions, a crisis pregnancy center that has never offered abortions.

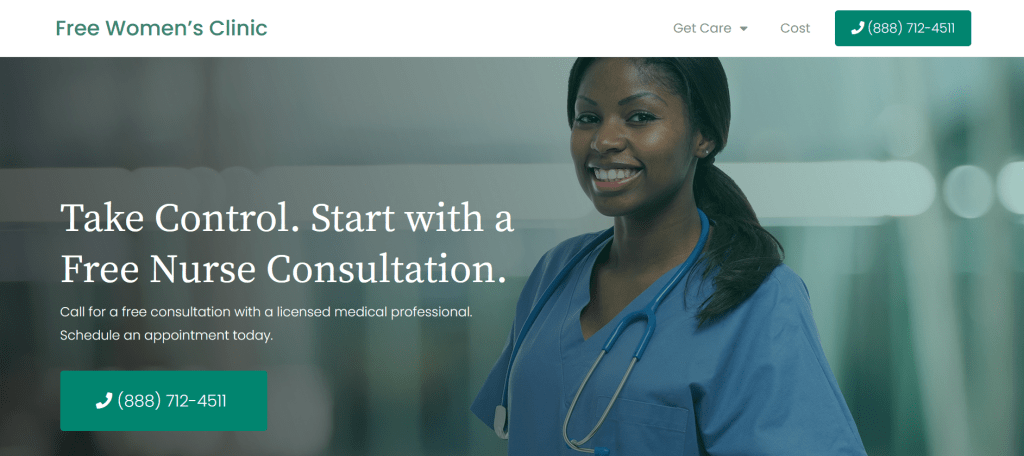

Another ad leads visitors to the page of Free Women’s Clinic, which is nearly identical to dozens of websites run by the Human Coalition, an anti-abortion nonprofit based in Texas that was recently the center of a New York Times investigation.

Google’s search app now labels which results offer or do not offer abortions, but these transparency labels do not show up if searching on Google’s web browser.

Anonymous search engines as Google alternative

Digital surveillance is another concern. Many apps, from games on Facebook to Fitbit’s activity tracker, record their users’ locations.

But big tech companies, including Google, Apple and Facebook, have not made public statements about what they will do if a law enforcement agency makes a subpoena, search warrant or other request for an individual’s abortion-related data.

Texas law enforcement agencies have already used Google location data in their investigations. In 2020, Texas law enforcement made more than 800 requests for Google’s location data, Bloomberg Law reported.

While a person seeking an abortion may not be subject to a violation under SB 8, law enforcement could serve a search warrant to find out who helped them, said David Donatti, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, of Texas.

Google announced plans to delete visits to abortion clinics from someone’s location history. The company also announced plans to update Fitbit and Google Fit so users can delete multiple menstruation logs at once.

But search history lives on Google servers, even if a user clears their search history from their personal server. Incognito mode also doesn’t prevent web tracking.

As an alternative to Google, people may turn to using anonymous search engines that do not store their browsing history, such as duckduckgo.com and startpage.com. Since these websites do not track users’ search history, they cannot turn that information over to law enforcement.

Abortion rights supporters have also made calls on social media for people to delete their period-tracking apps. Flo, a fertility and period-tracking app, came under fire in the past for sharing with Facebook when a user was having their period or intended to get pregnant.

After the fall of Roe v. Wade, Flo announced it was introducing an anonymous mode that had already been in the works, allowing users to remove name, email address and other identifiers from their profile. Users can also email customer support to request the company to delete their information.

Yes, you can still talk about abortions

While people have to be sensitive about sharing their personal health care information, that doesn’t mean people can’t talk about abortion as a general topic, Donatti said.

“For people in El Paso and statewide, none of these laws should infringe on our abilities to talk to each other and educate about what our rights are,” he said. “This is all First Amendment right. You should not worry that your conversations with family members, loved ones, church, are going to subject you to liability. We have the right to educate ourselves.”

Websites and pamphlets that share information about abortion rights, health care and how to obtain lawful abortions should be protected under the First Amendment of free speech, he said.

People should also not be fearful about their privacy when seeking abortion-related legal advice from a lawyer because of attorney-client privilege, said Tanya Pellegrini, senior counsel at The Lawyering Project.

“An attorney is not supposed to release that information,” Pellegrini said. “But generally if you go to an attorney for legal advice, that information would be confidential.”

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()