Coronavirus forces parents to change screen time plans

Screen time for Rachel Lubchansky’s 5th grade triplets used to be limited to two hours a week. That was before the coronavirus pandemic resulted in months-long school closures nationwide.

Now, there are new rules. The 11-year-olds are permitted an hour a day of “free rein” on screens. Their family isn’t alone in making this change.

As parents across the country continue to juggle working from home while also caring for their children, previously set limits on screen time have changed in the Covid-19 era.

“I needed some quiet time to just be able to focus on work, or be in the kitchen without 45 questions,” Lubchansky said, explaining that the shift didn’t happen overnight, but within the first five to seven days with their kids stuck at home.

She said she and her husband realized that their previous plan “was just not really going to be sustainable.”

Current guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics advises parents that toddlers under 18 months avoid all digital media (except video chatting) and preschoolers from two to 5 years-old limit screen use to only one hour a day of “high-quality programming.” For older children, the recommendation is more nuanced — setting clear limits and looking at what is being consumed.

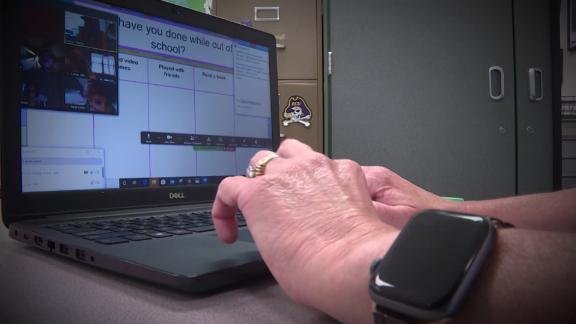

During the past several weeks of stay-at-home orders, however, many children are spending increasingly longer periods of time on phones, tablets, laptops or watching TV as their caregivers try to work, cook, do laundry, clean the house, or simply catch a break amid the chaos. And with tens of millions of children out of school for weeks now, technology has become the lifeline for kids to see their friends, family, and teachers, and do schoolwork.

Dr. Dimitri Christakis, the director of the Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development at the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, told CNN he now feels compelled to be something of an “absolutionist” for parents feeling guilty about increased screen time at home.

“I used to joke that the guidelines don’t apply to plane trips — except now it’s not an hours-long transatlantic flight, but a six to eight week one,” Christakis, who helped draft the AAP’s guidelines on screen time, said.

Content matters

In interviews with CNN, experts advised parents to stop agonizing over how much time their children spend on screens these days.

“As parents, we get stuck on numbers, [such as] two hours of screen time,” said Alexis Lauricella, director of the Technology in Early Childhood Center at Erikson Institute. “We like to have rules, but we got so stuck on the guidelines that we weren’t thinking on our own.”

For starters, virtual learning through screens or FaceTiming with grandparents doesn’t count toward the AAP’s screen time limit recommendations for children, which only further underscores the fact, according to Lauricella, that “the screen itself isn’t the problem — it has never been the problem. It was doing anything in excess.”

Instead, according to experts, parents should focus on the content of what their children are consuming as more time at home provides an opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of how children use technology.

“I always felt like in my heart, that all screen time is not created equal,” said Alana Rifkin Gelnick, director of the Early Learning Center at SAR Academy in the Bronx, New York. “If my 10-year-old son is writing a creative story on Google Docs, that’s not the same thing as my daughter watching two girls opening presents (on YouTube).”

Yet sometimes, for some parents working from home as their children are attached to devices — it isn’t always easy to tell the difference.

Victoria Griffith previously didn’t allow her 7-year-old daughter to use her computer or a phone for games during the week. But with her daughter’s school in New York using Zoom and recorded instruction for classes, she’s now in front of a screen in some form for roughly four to six hours per day.

“The lines can be blurred,” Griffith told CNN. “The first couple weeks (at home), I didn’t know if she was doing her reading or on YouTube (for fun).”

Headaches, distractions, and missing friends

While virtual learning doesn’t count as the type of screen time to guard against for most experts, the issue is nevertheless on teachers’ minds as the pandemic has required millions of students to switch to remote learning — and for many, several months longer than initially expected.

When Lubchansky asked her 11 year-old son’s private school why their school day online was less than four hours in the morning, the response from the administration was that teachers were trying to keep screen time to a minimum and provide other non-screen-based activities for the afternoon.

“Both of my girls have expressed getting headaches at times,” Lubchansky said. “They’ve said things like, ‘I’m just so sick of looking at the screen’ … so they even have sort of reached their capacity at times.”

Plus, concentrating in the face of remote instruction is not always easy, particularly for young children or those with learning differences.

“For young children, it’s a joke,” Dr. Christakis said. “It’s not practical — it’s not a reasonable expectation” that they are developmentally capable of sitting in front of a screen for prolonged periods of time like it’s a “normal school day.”

For that reason, Zachary Trail, who teaches preschool in Chicago on the southwest side, only teaches 20 to 30 minutes a day through a live component, with additional activities for students to work on at home.

But mostly, teachers have observed that their students simply miss physical, face-to-face time with their friends.

“What keeps me up at night is actually not the direct screen time but the social interaction,” Gelnick said. “That’s very, very hard to replicate on a screen.”

And as more and more states announce school closures through the end of the academic year, parents worry about the implications of kids’ long-term screen use and how they’ll ever return to their previous “ideal” screen rules.

“When things resume to some semblance of normalcy,” Lubchansky said. “I think we’ll have to find another new normal — that’s going to be some combination of what feels good for the kids (and) what feels good to us.”