Voter ID laws are disenfranchising transgender and nonbinary people as anti-trans legislation reaches record levels

Canva

Voter ID laws are disenfranchising transgender and nonbinary people as anti-trans legislation reaches record levels

Hands attaching an “I Voted” pin to a denim jacket.

In Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, a transgender woman went to her polling place to cast a vote, only to be met with poll workers demanding to see her ID. Though no law required voters to provide ID when casting a ballot in the state in 2019, the poll workers scrutinized her. They almost didn’t let her vote because, as she later alleged in a discrimination lawsuit against the county and state, her appearance did not match the gender of the legal name listed on her ID.

Jane Doe, the pseudonym she used to file the suit under, is far from the only trans voter to experience this when trying to exercise a constitutional right. Similar experiences have been reported in states like Tennessee and Texas, and it is likely the occurrence is underreported. Nearly a third (30%) of trans voters have experienced verbal harassment because the gender marker or name on their IDs doesn’t match their gender presentation, according to VoteRiders.

In states with voter ID laws, transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming voters are at particular risk of harassment, questioning, or even being turned away from the polls. But fear of scrutiny, particularly when nearly 7 in 10 transgender Americans (68%) don’t have valid or accurate ID, can keep would-be voters from even attempting to cast a ballot.

As legislation targeting transgender Americans continues its record-breaking expansion, the scope of the trans voter disenfranchisement issue is still not widely understood. To that end, Stacker talked to experts and sifted through data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Williams Institute, and the Movement Advancement Project to examine how voter ID laws disproportionately impact transgender and nonbinary voters.

![]()

Eliza Siegel // Stacker

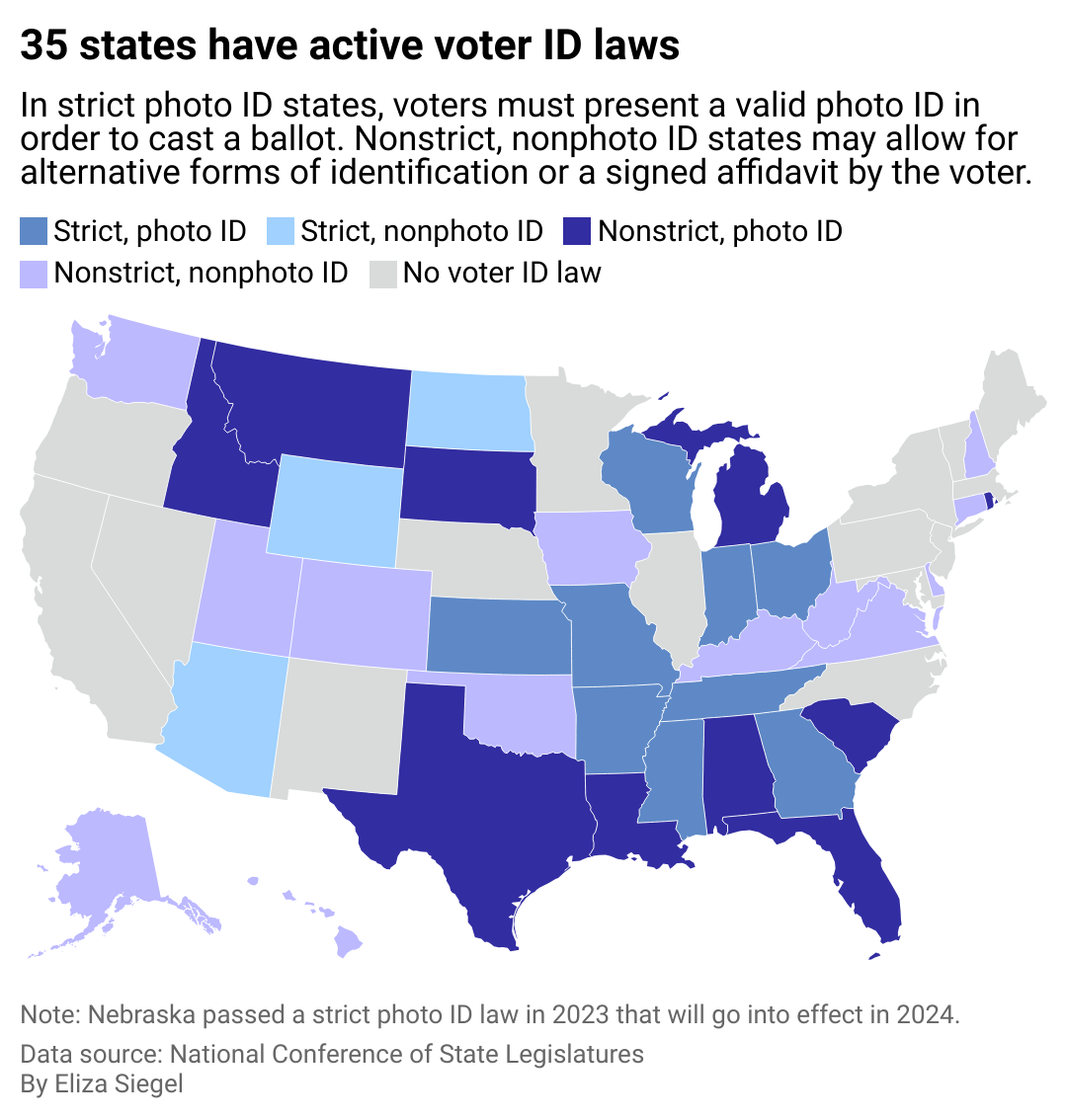

Voter ID laws make voting difficult for over 11% of Americans

This map of the U.S. shows the 35 states that have active voter ID laws. In strict photo ID states, voters must present a valid photo ID in order to cast a ballot. Non-strict, non-photo ID states may allow for alternative forms of identification or a signed affidavit by the voter.

Voter ID laws vary in type and level of strictness but are generally intended to verify the voter’s identity against registration records. Depending on the law, they can require someone to present a form of photo or nonphoto identification at the polling place. Some stricter laws require a government-issued ID and do not offer other options, like provisional ballots, to those who don’t have the proper documentation.

The current prevalence of voter ID laws—which exist to various extents in 35 states—can lead some to believe they are ordinary or at least have a well-established historical precedent. On the contrary, these laws are a modern phenomenon; the first voter ID law was implemented in 2006 in Indiana and required voters to present an up-to-date photo ID at the polls. The Supreme Court upheld the law’s constitutionality in 2008, and a cascade of other states implemented versions of the same policy in the following years.

Prior to 2006, the only time ID was required at the polls was when first-time voters did not include a form of identification when registering to vote.

Proponents of the laws argue that they work to prevent voter fraud and ensure election security. But those who oppose voter ID laws say these play on fears of demonstrably rare fraud to keep some of the nation’s most marginalized people from exercising their constitutional rights.

“Voter ID laws are a solution in search of a problem,” Jody Herman, senior scholar of public policy at the Williams Institute, told Stacker.

She pointed to several studies that have concluded voter fraud in the U.S. is infrequent. An early study by the Brennan Center for Justice found the rates for voter fraud were as little as 0.0003% and 0.0025%. Particularly rare are instances of voter impersonation, the type of fraud voter ID laws are purportedly in place to prevent. A comprehensive 2014 Washington Post study found that, out of 1 billion ballots cast, only 31 instances of impersonation fraud were credible. Even then, the number is likely inflated since any and all credible claims were counted—not just prosecutions or convictions.

“One has to wonder—if there really is no voter fraud problem—then what problem are voter ID laws trying to correct?” Herman said.

Eliza Siegel // Stacker

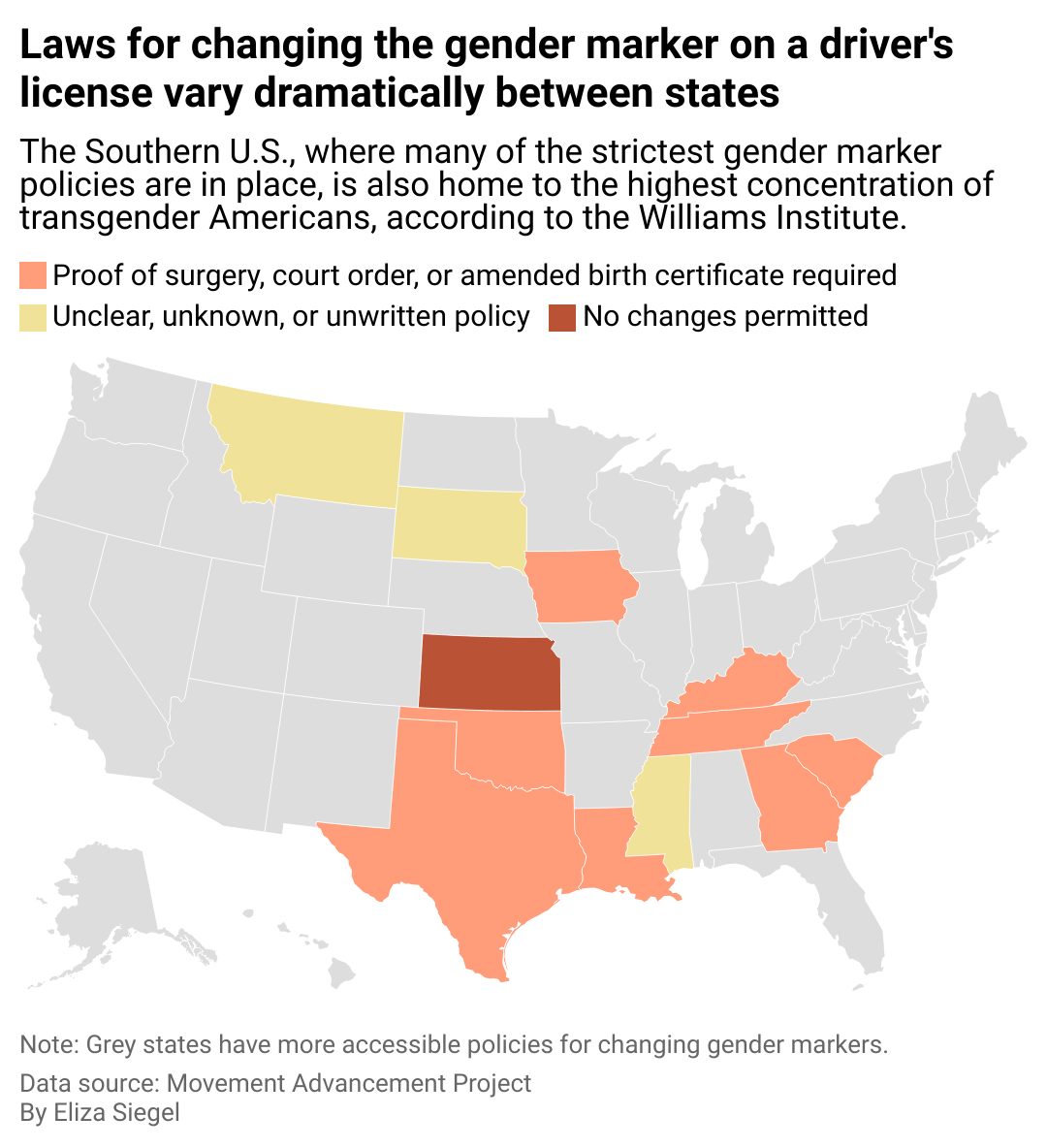

Transgender voters can be put at risk by voter ID laws

This map of the U.S. shows the varying laws for changing the gender marker on a driver’s license by state. The Southern U.S., where many of the strictest gender marker policies are in place, is also home to the highest concentration of transgender Americans, according to The Williams Institute.

The majority opinion in the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision to uphold the first voter ID law stated there was not “any concrete evidence of the burden imposed on voters who now lack photo identification.”

But almost 29 million voting-age Americans did not have a valid driver’s license in 2020, according to a 2023 study by the University of Maryland’s Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement.

For those who have access to valid ID, it is easy to assume everyone else does too. This belief is particularly common for white upper-middle-class lawmakers, according to Cassius Adair, an assistant professor at The New School whose research has focused in part on the history of driver’s licenses in the U.S. At least 9 in 10 white American adults (92%) have a nonexpired driver’s license, compared with nearly 4 in 5 Hispanic American adults (77%).

“There’s a prevailing assumption amongst lawmakers that everybody has a state ID, and it’s easy to get, and if you don’t have one, it’s your fault,” Adair told Stacker.

Many of those without valid ID are young people; older adults; Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous adults; low-income Americans; immigrants; and people without housing. Formerly incarcerated Americans and people who went through the foster care system also frequently lack valid IDs.

Common obstacles to obtaining a state ID include financial constraints, complicated document requirements like birth certificates or Social Security cards, and needing proof of residency.

Out of the roughly 414,000 voting-eligible transgender Americans living in states with both voter ID laws and mostly in-person voting, nearly half (about 203,700) do not have an ID that matches their name and gender, according to the Williams Institute.

Showing up to the polls with an ID that doesn’t match one’s name or appearance can lead to being turned away and make trans voters vulnerable by effectively outing them as transgender, according to Logan Casey, a senior policy researcher and advisor at the Movement Advancement Project.

“Research shows that when transgender and nonbinary people show IDs that don’t match their gender identity, they are more likely to experience violence or harassment or discrimination or be denied services,” Casey told Stacker.

For the large percentage of transgender Americans without a valid or accurate ID, there are even more roadblocks to obtaining or updating an identification document. “Many states have very restrictive and outdated laws that make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for transgender and nonbinary people to update their identity documents,” Casey said. “That’s all preexisting the last couple years, where we’ve seen a dramatic escalation in anti-LGBTQ and anti-transgender legislation.”

Eight states—including Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina—require proof of surgery for transgender and nonbinary people to change their gender marker on driver’s licenses. The American Medical Association called for removing surgery requirements for changing ID documents in 2014 since not all trans and nonbinary people desire, or are able to access, surgery or other forms of medical transition.

Earlier this year, Kansas became the only state to prohibit changes to gender markers on both birth certificates and driver’s licenses.

Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

There’s a lot on the line for trans voters

“Notice Acceptable ID Required” sign outside a Virginia polling place.

There is no way to tell how widespread the issue of trans voter disenfranchisement really is due to a lack of studies and the sensitivity of the issue. But the potential impact is massive, with roughly 878,300 transgender adults being eligible to vote in the 2022 general election in the U.S.

The 2020 presidential election—in which Joe Biden avoided a tie in the Electoral College by 44,000 votes—is a prime example of the impact of each voter, according to Herman. Roughly 65,000 transgender adults who do not have accurate IDs live in states with strict voter ID laws.

“That could sway an election,” Herman said. “Every vote matters.”

In addition to major presidential races, equitable voter participation matters immensely on the local and state levels.

“These attacks on democracy are making it more and more difficult for people across the country to actually elect representatives that share their values,” Casey said. Record numbers of anti-LGBTQ+ bills have been introduced this year—such as bills that profoundly impact the health and safety of transgender youth and adults—despite most U.S. adults being opposed to discrimination against LGBTQ+ people.

As of September 2023, bans on gender-affirming health care for young transgender people exist in 22 states.

“You end up getting these policy outcomes at the state level that are dramatically out of step with what people in that state actually want and care about and prioritize,” Casey said.

Jeff Swensen // Getty Images

Obstacles to voting are nothing new

A voter shows identification to an election judge during primary voting in Ohio.

Gender- and race-based voter suppression have a long history in the U.S. After the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, granting Black men the right to vote, loopholes like poll taxes, as well as violence and intimidation tactics, prevented newly enfranchised voters from exercising their rights.

Women gained the right to vote in 1920. Still, many men and women of color could not cast a ballot until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolished discriminatory voting restrictions like literacy tests. The 24th Amendment abolished poll taxes in national elections the year before.

Obstacles to voting still exist, with voter ID laws being one of a myriad of roadblocks to the polls, according to Kat Calvin, founder of the organizations Spread The Vote, Project ID, and Project ID Action Fund.

High-income Americans have significantly higher voter turnout than low-income Americans, according to Census data. That’s largely due to microbarriers like finding child care, taking time off of work, and accessing transportation, which makes voting more difficult for low-income Americans, Calvin said.

In states with strict voter ID laws, the obstacles are even greater. In Calvin’s mind, the cost burden of obtaining an ID—which can range anywhere from $5 to $84 in different states—constitutes a poll tax.

Voter ID laws “put a barrier in front of a constitutional right that, already, this population doesn’t get a chance to exercise,” Calvin said.

For transgender and nonbinary Americans, who already face a significant wage gap and higher poverty rates compared with all Americans, these financial barriers can be enough to pose significant challenges to voting, even without considering the other safety and logistical concerns posed by voter ID laws.

Sean Rayford // Getty Images

People are pushing back

Signs inform voters at a polling location in North Carolina.

In addition to advocating for voter ID laws to be repealed, organizations and some states are finding ways to protect trans voters and voting rights. In California, the official poll worker training standards include specific guidance on the fair treatment of gender-nonconforming voters. Polling sites also prominently display posters and brochures informing voters of their rights.

Herman says more states could consider adopting similar policies to protect transgender voters.

Organizations like Calvin’s are working more broadly to make obtaining IDs more accessible to people who face obstacles. The Project ID Action Fund supports the IDs for an Inclusive Democracy Act, a congressional bill that would create a free, optional federal ID that would meet ID document requirements in each state.

Project ID Action Fund’s sister organization, Spread The Vote, also works directly with people to help them acquire IDs. Beyond difficulties with voting, people without ID face challenges in almost every facet of their lives, including applying for jobs and housing, accessing health care and social services, and opening a bank account.

“One of the things that our clients say all the time when they get their ID is, ‘I’m a person again,’ because you really don’t exist without one,” Calvin said.

She pointed out that the rights of many of the most marginalized communities depend upon everyone being able to vote: “If you need an ID in over 30 states to vote, then, to me, that constitutes an emergency.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.