‘Cassandro’ film depicts trailblazing borderland luchador

by Cindy Ramirez, El Paso Matters

September 12, 2023

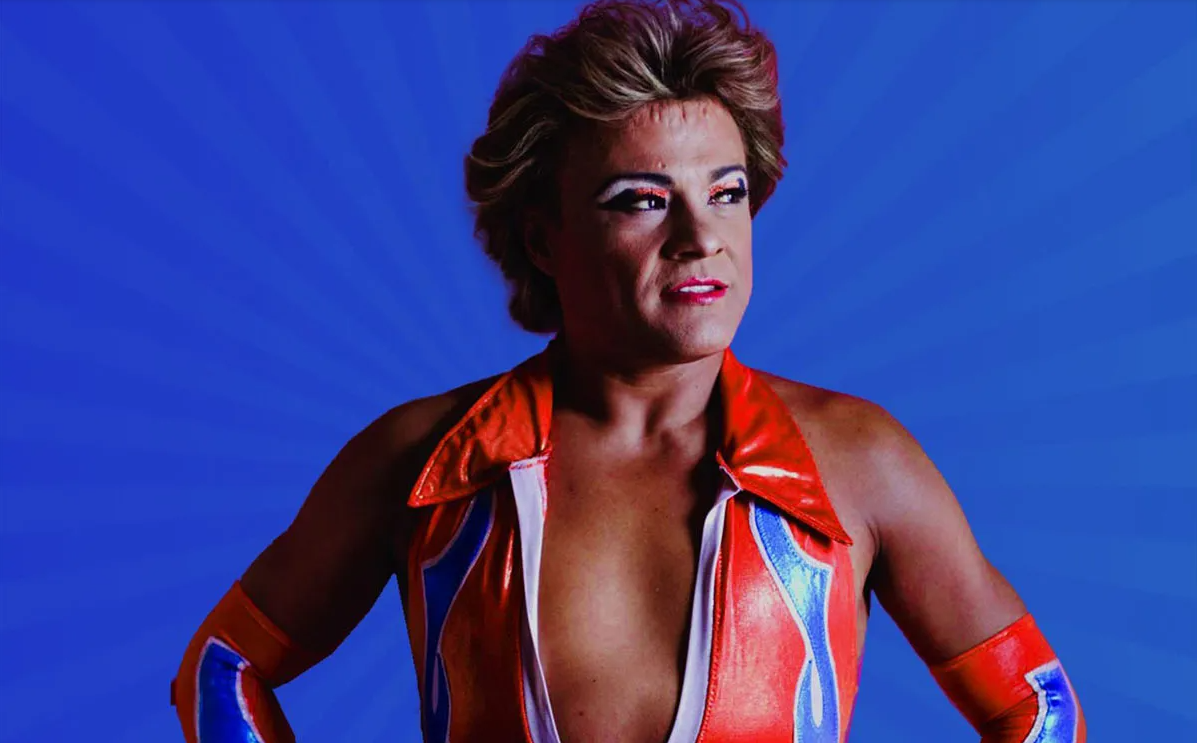

In the dressing room of the Gimnasio Josué Neri Santos in Ciudad Juárez, Sául Armendáriz carefully applies glimmering eye shadow, long fake lashes and red lipstick. He styles his sandy blond hair with a curling iron – and lots and lots of hairspray.

He slips into his lycra tights, a shiny spandex singlet and high wrestling boots. He tops the look with a bejeweled cloak with a train so long that it drags several feet behind his 5-foot-5 frame. A Spanish version of Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” plays on the intercom as Armendáriz enters the ring.

It was the early 1990s and the El Paso-born wrestler’s career was taking off, blazing trails as the first openly gay luchador exóticoin Mexico.

He became Cassandro el Exótico. And for more than 30 years in the ring, he showcased his flamboyant costumes alongside his athleticism and signature wheelbarrow victory roll – and often, his liplock closing move.

Now his story is being told in “Cassandro,” a R-rated biopic that’s set to release in select theaters on Friday and on Amazon Prime on Sept. 22. The movie tells of Armendáriz’s rise to fame, as well as his tumultuous relationships with his mother, his secret lover and his absent father.

“My first view of lucha libre was on television, in black and white. And then as time passed, I started going to the luchas and it was just amazing!” Armendáriz said in a previous film about his life – the 2019 documentary “Casandro, the Exótico” by French filmmaker Marie Losier. “It was like a free therapy session. You forget all the stuff that happened to you at home or in school and all the problems.”

The life of the 53-year-old certainly reads like a Hollywood movie: He grew up poor in a border town and was molested at a young age. He was outcast by his father and enduring homophobic attacks by his peers. He combatted alcohol and drug addictions and attempted suicide. His stints in and out of the ring left his body battered and scarred.

Armendáriz’s latest battle is aphasia, a disorder resulting from damage to the part of the brain that controls language. He had a brain embolism in May 2021 and has since been in therapy to try to regain his speech and other motor skills, recently conducting selected interviews via text and through his publicists.

He was unavailable to meet with El Paso Matters in time for this story, his publicists said.

Armendáriz recently signed with Motion Entertainment Lifestyle Networks to create a “new brand and conversation focused on perseverance, inclusivity and faith,” founder John Pina told El Paso Matters. The events consulting and public relations firm is marketing Cassandro’s image and legacy, including through merchandise such as t-shirts and dolls, Pina said.

That comes as buzz around the movie builds, by Tuesday earning a 96% rating on the movie website Rotten Tomatoes with 45 reviews.

Co-written and directed by Oscar and Emmy winner Roger Ross Williams, “Cassandro” stars Gael García Bernal, whose films include “Amores Perros,” “The Motorcycle Diaries” and “Bad Education.” The movie also stars Perla de la Rosa, Joaquin Cosio and Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio – best known as Bad Bunny. It features cameos by Mexican lucha superstars Gigantico, El Mysterioso and El Hijo del Santo.

The movie premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

“It was really important to tell an uplifting story about finding your true self, your true purpose, and finding your community in the world,” Williams said at a post-screening Q&A featured on the Sundance Institute website. “It inspired me, but I hope it inspires everyone — not just the LGBTQ+ community — but everyone.”

At the event, Bernal said he hoped movie audiences would take “what Cassandro gave to lucha libre, which is a face of joy. This (joy) comes in with an added salt of misbehavior and imagination.”

Becoming Cassandro

The fourth of six children, Armendáriz and his siblings would spend his school days in El Paso and most weekends across the border in Juárez, he said in the “Casandro, the Exótico,” documentary.

After church on Sundays, the family would catch a lucha match. The exóticos – men who wrestled in drag – were regarded as the comedy of the show, he said in the documentary.

His interest in the sport piqued as he came to embrace his sexuality – determined that he’d be a respected luchador in drag and not a ridiculed drag queen who wrestled, he said in a 2014 interview with The New Yorker. He started training at 15, dropped out of school and had his first match at 17.

At first, he worked as a masked wrestler by the names of Andromeda and Mister Romano, then unmasked as an exótico named Rosa Salvaje, or Wild Rose. He later adopted the ring name Cassandro, after a Tijuana brothel keeper named Cassandra, he said in a recent Univision interview.

He started making his own costumes – using his sister’s quinceañera dress for his first cape, his sistertold Univision. As his capes got longer and his hair higher, he was nicknamed the “Liberace of Lucha Libre.”

Wrestling became his religion, his family, he states in the 2019 documentary.

“Bendita lucha libre, nunca te acabes,” Armendáriz often posts on social media. “Blessed wrestling, never come to an end.”

‘Bendita lucha libre’

By the early 1990s, Armendáriz was a well-regarded luchador on his way to wrestle El Hijo del Santo, the son of famed Mexican luchador El Santo. The match-up received such negative backlash for pitting a gay wrestler against a macho centric family name that Armendáriz attempted suicide, he told The New Yorker. His wrestling partner, Pimpinela Escarlata, found him and saved his life.

He got in the ring a week later, losing to El Hijo del Santo but gaining the respect of the wrestling community. He became the first exótico to hold a championship belt with the Universal Wrestling Association in 1992, holding the lightweight title until 1994, the online wrestling database CageMatch states.

“I've had a lot of doors shut on my face because of my sexual preference and because of being an exótico,” he said in the documentary. “But people didn't give me the chance to see my work inside the ring.”

Once he stepped in the ring, he said in the documentary, he earned their respect.

Over the next decade, he worked the independent circuit and several other wrestling associations. He started using drugs and alcohol and fought bouts of depression. He’s been sober since June 2003, turning to spirituality and therapy to stay clean.

From 2011 to 2014, he held the National Wrestling Alliance welterweight championship belt.

Some of the new “Cassandro” movie scenes were shot in and around El Paso. Among them was at Stanton and First streets in Downtown for a scene where Bernal was to be admiring a mural of Cassandro. The mural by El Paso artist Cimi Alvarado depicts Cassandro’s face as a combination image of Armendáriz and Bernal created by artist Fabián Cháirez.

Earlier this year, he was inducted into the Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide Hall of Fame run by the Mexican wrestling promotion company, and on Monday was honored with a resolution presented to him by El Paso County Commissioners Court.

The resolution states in part that Cassandro has “represented the values and culture” of the borderland and that his “fight for acceptance and representation is a testament to the resilience, diversity, perseverance, and strength of our border community.”

Unable to speak much, Armendáriz waved and smiled then simply uttered, “Cassandro!”

“Cassandro”

“Cassandro,” a rated R biopic on the life of Saul Armendáriz, or Cassandro el Exótico, is set to release in theaters on Sept. 15.

You can find movie listings in El Paso on the Fandango website.

It will be streamed on Amazon Prime starting on Sept. 22.

You can watch the 2019 documentary “Casandro, the Exótico,” by French filmmaker Marie Losier, on Tubi.

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()