Springfield Haitians weigh their future as Trump threatens deportations

By Omar Jimenez, Caitlin Stephen Hu and Matthew Reynard, CNN

Springfield, Ohio (CNN) — It’s just past 4am.

Daniel Aula is in his one room apartment praying, thankful he’s alive, and thankful he’s heading to work.

Aula, originally from Haiti, has been living in Springfield over a year now. He knew about the quiet Ohio city through a friend and heard it had not only a low cost of living but also great work opportunities to match.

Why not?

It’s a world better than what he was running from. Aula had been a police officer back in crime-wracked Haiti, until he wasn’t. His house was burned down, he went into hiding, and was told people were coming to kill him.

“I know that. There are two friends who let me know that,” he told CNN.

“My life was not safe,” he told CNN. “I decide to leave Haiti.”

While Aula has found opportunity in Springfield, he’s also found himself in the middle of a bitter national debate on immigration heading into November’s election, fueled in this case largely by rumors and threats.

The city of Springfield estimates there are between 12,000 and 15,000 immigrants living in Clark County, the county that holds Springfield, most of them believed to be Haitians arriving in just the past four years.

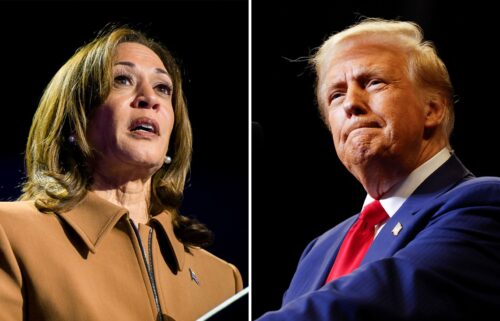

The image of a city dramatically altered by immigration has been seized upon by former President Donald Trump and his running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance — who have made criticism of the Biden administration’s immigration policy a cornerstone of their campaign.

Trump falsely told about 67 million viewers that Haitians in Springfield were “eating the dogs” and “eating the cats,” during the presidential debate on September 10.

And Vance has made repeated false claims about Haitians, fueling rumors that they kill pets and do not have legal status in the country.

Trump is already threatening to deport Springfield’s Haitian residents if elected.

“You have to remove the people, and you have to bring them back to their own country,” he told News Nation in an early October interview.

A shot at a new life

Springfield is Aula’s chance at a new life. He’s taking English classes, but he’s had so much to learn, namely how to get a job. Many in Springfield have been eager to help him, and to hire him.

Not long after he got to Springfield, Aula started working at Pentaflex, a company focused mainly on building metal stampings and assemblies for safety related functions like the brakes on a truck.

CEO Ross McGregor, whose family has been involved in manufacturing here for decades, has nothing but praise for his Haitian employees. To lose them would be a blow to his business, he told CNN. McGregor hired his first Haitian worker “three, four years ago” not because he sought them out specifically but because he needed dependable workers.

“Retail demand was climbing through the roof,” McGregor told CNN. “We were having a real hard time with people that would apply for a job and then they wouldn’t show up on the floor.”

“Or they’d come in and they’d work for half a day and they’d just leave,” he said. “That is, you know, a real problem when you’re running a production facility. You need to have a reliable workforce that you can count on to be at work every day.”

In contrast, his Haitian employees seem eager to work, he says. He walked CNN through his factory, pointing out work instructions available both in English and Haitian Creole.

“I want to dispel one thing,” he told CNN unprompted: “We don’t bring (Haitian workers) in at a substandard wage and work them and pay them any less than we would any other employee,” he said. “There are no Haitians that are taking anybody’s jobs. I mean, if you want a job, you can get a job. And I just encourage people to have a little bit of empathy for where the Haitians are coming from.”

“I don’t know a person in this town that wouldn’t want to get the hell out of (Haiti),” he said.

The rapid arrival of Haitians in Springfield has created both growing opportunities and pains. Some would come with any population increase; some have been specific to the culture differences and language barriers.

Multiple city and state officials point to the population influx of Haitians as a major boost to Springfield’s economy.

Over the last several years, “We’ve seen more growth than we’ve seen for decades past,” said Springfield City Manager Bryan Heck, including a “revitalization and resurgence of our downtown.”

The growing pains, however, were maybe encapsulated best by Springfield Mayor Rob Rue during a July 2024 City Commission meeting where he told a resident, “We were not in control of this.”

“We didn’t get a chance to have an infrastructure in place if there are going to be 20,000 more people from ‘20 to ‘25 — we didn’t get to do that. So, the most frustrating thing is we’ve got to spend tax dollars that were already in a flat budget, that we’ve got to vote on to try to take care of 15,000 more folks that are here and make sure that everybody has a safe environment to be in,” he said.

Springfield’s growing population has put pressure on services like health care, including wait times for things like blood pressure screenings, vaccinations and more. Visits requiring interpreters also take longer, making lines stretch even further. It’s part of why the state of Ohio helped open a mobile healthcare clinic, to try and ease some of those pressure points. State officials say they saw close to 100 patients in about a week’s time, which exceeded expectations.

“The system’s been strained for a couple of years, we just now have people paying more attention,” said Chris Cook, health commissioner for Clark County, which includes Springfield.

Maternal health care has been an especially poignant issue because of “poor prenatal care” in Haiti, he said. “You’ve got moms who are walking in the hospital that are in labor. They’re ready to give birth in probably the next couple hours, and they’ve never had a single prenatal visit,” Cook told CNN.

Cook said they also encourage new mothers to be part of their Women Infants and Children (WIC) supplemental nutrition program and hope to have appointments within 10 days of the baby’s birth. But over time, waits grew to two months, he said.

“That’s not just our Haitian moms,” Cook said. “Everybody’s in the same line.”

Another major area of concern in Springfield has been housing, with signs of stress dating all the way back to 2018 in regard to availability and cost — years before Haitians began arriving after the Biden administration approved Temporary Protective Status in 2021 due to the violence, human rights abuses, and dire economic situation in Haiti.

City Manager Bryan Heck sent a letter to Sens. Sherrod of Ohio Brown and Tim Scott of South Carolina — then cc’d Vance in July of 2024 — regarding “a significant strain,” regarding housing.

“I didn’t call it a migrant crisis. I didn’t call it an immigration crisis. It’s a housing crisis,” Heck told CNN. “The pace of growth for our community is just — was not sustainable and continues to not be sustainable unless we get some additional support from the state and federal government,” Heck said.

Rent also went up, partly from the increased demand of a new population but driven also by the “greed of landlords,” as Mayor Rue put it during a July City Commission meeting. Prices were also likely affected by nationwide inflation in recent years.

While Trump has claimed the influx brought “dangerous” criminality, Clark County Prosecuting Attorney Daniel Driscoll, a Republican, told CNN last month that was not the case.

“During the time that I’ve been with the prosecutor’s office, which is 21 years now, we have not had any murders involving the Haitian community — as either the victims or as the perpetrators of those murders.” He confirmed to CNN this week this was still the case.

Overall, according to the City of Springfield, “Haitians are more likely to be the victims of crime than they are to be the perpetrators in our community. Clark County jail data shows there are 199 inmates in our county jail this week. Two of them are Haitian. That’s 1% (as of Sept. 8).”

Andy Wilson, director of the Ohio Department of Public Safety, said at a September press conference, “The No. 1 issue we have in the public safety space with the Haitians, it’s not crime, it’s not violence — it’s the driving, that’s the public safety issue. So, what we want to do is we want to get driver’s education to that population.”

It’s an issue that state officials have found hard to immediately tackle, given that adults in Ohio can test for a driver’s license and receive it without having to go through a formal training program.

Governor Mike DeWine recently directed the Ohio State Highway Patrol to support Springfield Police with traffic enforcement “to address the increase in dangerous driving in Springfield by inexperienced Haitian drivers and all others who disregard traffic laws.”

While some Springfieldians gripe about the effects of immigration, others are stepping up. Cook and local United Way director Kerry Lee Pedraza, who grew up here, today co-chair what’s known as the “Haitian Coalition,” which is a combination of private and public entities working behind the scenes to find solutions that work for everyone in Springfield, not just Haitians.

In 2022, at their first meeting, Pedraza said there were 45 people from different organizations who showed up. They’ve only grown since then, but part of the problem recently is they have not had the “financial resource to help us to continue to do it, and to do it at a speed where everyone in the community is going to feel that there’s some relief.”

Regardless, the multilateral level of coordination across sectors has been “incredibly effective,” she said. “It actually could probably be a master class of how any community needs to come together around, take any social issue, and work together to create a really good solution.”

“Today it might be the Haitian community, tomorrow it could be a different community,” Pedraza told CNN.

Living under the shadow of threats

Haiti has been ravaged by violent gang warfare in recent years. Aula’s wife and daughter are still in hiding there, he told CNN.

In early October, at least 70 people were killed, including three infants, in a gang attack in central Haiti, according to the United Nations Human Rights Office.

The UN reports more than 3,600 people have been killed so far this year. Hundreds of thousands of Haitians have been forced to flee their homes after gang attacks.

Given Haiti’s anarchial unrest in recent years, Haitians were added to a Biden-Harris administration parole program, limited to only a few countries, that allows vetted participants to enter the United States as long as they are sponsored by US residents.

Others have Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a renewable program that shields some at-risk nationalities from deportation and allows them to live and work in the country for a limited period of time.

Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas designated Haitians for Temporary Protected Status starting in 2021 and has subsequently extended and redesignated Haiti through February 2026.

Those in the United States under the parole program are able to apply for TPS.

“We frequently see people who have just entered within the past month or two,” said Katie Kersh, a senior attorney at Advocates for Basic Legal Equality (ABLE), where she specializes in immigration and civil rights and has represented Haitians for years.

She and her team have been working to provide free legal clinics assisting Haitians in Springfield and beyond who have arrived in the past two years assisting them with applications for TPS, asylum, work permits and more.

Kersh said Haitians do hear Trump’s comments about deportations, and even she “can’t tell anyone that there’s no likelihood that there could be some sort of mass enforcement action.”

However, a broader revocation of previously granted parole or TPS would “be definitely challenged in the courts and probably successfully. So that’s a big thing that we’re trying to tell people, that it would be really, really procedurally and legally difficult for that to happen,” Kersh said.

Still, many Haitian residents in Springfield live in fear of Trump’s threat of removal, unsure over their future and their safety.

Dieff-Son Lebon is one of those Haitians. CNN met Lebon as he got off work at a construction site before heading to dinner at one of the multiple Haitian restaurants that have opened in Springfield.

But first, he made a stop with an immigration advocate to consider his options if there was any mass deportation effort that included him. He’s been a little more nervous than usual lately.

“As I was walking down the road, a white man drove by and yelled Trump!” Lebon said in Creole. Lebon took it as a threat.

“I was scared! Because I was on the street, I was going to buy something, and I was also walking on foot, so I was scared, and I hurried to get home,” he told CNN.

He said he had never dealt with anything like that since living in Springfield.

“It was peaceful here, understand, there were no such things. Everything started after the remark,” he said.

The “remark” in question came during the presidential debate in early September, but it all likely stemmed from August 28, 2024.

A Springfield resident reported to police that she suspected her Haitian neighbors of chopping up her cat after finding “meat” in the backyard.

Soon after, social media posts began circulating about pet-eating Haitians and were even promoted by neo-Nazi groups, some of which have shown up to Springfield in person marching against Haitians being there.

Just days after the initial police report, the owner’s cat “Miss Sassy” was found safe in her basement. While the literal cat was found, the metaphorical cat was out of the bag, and the claims spread far and fast, eventually making its way onto the debate stage.

First Vance’s team picked up the rumors, with the senator claiming, “You have a lot of people saying ‘my pets are being abducted’” and “’slaughtered right in front of us.’”

And then Trump made the claim at the debate.

The claims have been refuted by Springfield officials and City Manager Bryan Heck told CNN that Vance’s team knew there was no substantiated evidence.

“I had a call from one of Vance’s staffers and asked, ‘Hey, are the rumors true of pets being taken and eaten by the immigrants in your community?’ I said no,” Heck told CNN. “It’s a baseless claim,” he added.

“To see that continue to be retweeted by Vance himself the next day and then sitting there watching the presidential debate” was “difficult,” Heck said.

Days after the presidential debate, city buildings and schools were hit with multiple threats of violence, prompting evacuations and cancellations of events. While state officials later said these threats ended up being hoaxes, many “from overseas,” they still prompted real evacuations and warranted a beefing up of security both for city officials and schools.

“To have threats thrown at my family and thrown at my house to explain to my 12-year-old why a bomb dog has to sniff our house to see if something is explosive there. That’s tough,” Heck told CNN.

Gov. DeWine’s ‘obligation to tell the truth’

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine was born in Springfield, Ohio. While he grew up in a town nearby, he took his now-wife, Ohio first lady Fran DeWine, on dates to Springfield when they were both in high school.

The DeWines fund a school in the dangerous Cité Soleil, an impoverished neighborhood in Haitian capital Port-au-Prince — an area entirely under gang control, where thousands of civilians live as a captive population.

DeWine is also a Trump-supporting Republican. All those aspects of his life have collided this past month in a way he simply described as “kind of strange.”

“As governor, I have an obligation to tell the truth and talk about Springfield,” DeWine told CNN.

While DeWine readily acknowledges not everything has been perfect as the Haitian population has grown, he also said it’s unmistakable that “if you look at Springfield’s growth in the last few years, that’s been fueled, a lot of it by the Haitian immigrants who were taking jobs that were open.”

He even said he had one employer “look me in the eye” and tell him, “’I don’t think our company really would be here today if it wasn’t for Haitians.’”

Historically, Haitians are hardly the only group to immigrate to Springfield. For starters, “The Gammon House” in Springfield was a stop on the Underground Railroad, serving as a symbol of a step toward freedom and a new life for the freed slaves in America. Some of the first Greek establishments opened in Springfield in the early 1900s, but the area also saw an influx of Germans, Irish, and later on Hispanics.

In 1970 the population in Springfield was around 82,000. The 2020 federal census showed a drop to around 58,000.

“Pumping resources into the community is how communities grow. This is how we grow,” DeWine told CNN.

While Trump’s deportation threat may not be easily carried out, DeWine believes removing Haitians from Springfield would not be good for the city.

“It would be a mistake to kick these people out who are working, who are raising their family, who are productive members of society. I think that’s an economic mistake. I think it’s a moral mistake as well,” DeWine told CNN.

But not enough of a mistake to change his vote.

“I support my party,” he said. “Going against the nominee of the party, I think makes me a less effective governor of the state of Ohio.”

“I think the decision to who you support for president is based upon multiple issues,” he said.

And, he said, he is supporting the Haitian community.

“I make my position very, very clear. I don’t think they should be thrown out. I think it would be a dramatic mistake. I think it’s wrong,” he told CNN.

Daniel Aula’s fate may hang on how America votes on November 5. But he is sanguine about the heated rhetoric around his community’s presence in town — and still, despite everything, grateful to be here.

“The world, it’s like a village,” Aula said. “Like a village, angry people and happy people have to live together.”

“Immigrants cannot take the place of people, American citizens,” he told CNN while driving through Springfield. “They just come to collaborate.”

“Even the people (who are) angry about me, I love all of them,” Aula said. “I love all of them, even the people that hate me.”

Reporting contributed by CNN’s Catherine E. Shoichet, Kate Sullivan and Daniel Dale.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.