Thousands of schools at risk of closing due to enrollment loss: An exclusive report

Canva

Thousands of schools at risk of closing due to enrollment loss: An exclusive report

empty school hallway lined with lockers

Days before Christmas, the school board in Jackson, Mississippi, voted to close 11 schools and merge two more — a drastic move that parents in the district had long feared. Some on the list have lost 30% or more of their students since 2018.

Despite the district’s high poverty, Superintendent Errick Greene said he could no longer afford to staff social workers and counselors at schools with long stretches of declining enrollment. Many older buildings were falling apart. It made no sense, he said, to have plumbers and HVAC technicians “racing hither and yon across the city” each morning to keep them running.

“Should we really be investing this money in these school buildings if they’re at best at half capacity?” he asked.

Such questions are weighing heavily on district leaders throughout the country. Fresh from the academic struggles that followed the pandemic, and with federal relief funds soon to run out, they now confront a massive enrollment crisis.

“I’m not surprised people didn’t want to talk about this until last fall,” said Brian Eschbacher, an enrollment consultant. “There was always hope that the kids were coming back.”

But most have not — part of a decline that is projected to continue throughout the decade. Oregon, New Mexico and West Virginia are among the states expected to see enrollment drop at least another 10%.

A new analysis of national enrollment data, prepared by researchers at the Brookings Institution and augmented by reporting from The 74, offers the most detailed look to date at how the crisis is playing out at the school level, as well as the districts that face — or will soon face — tough decisions about closures and cuts.

‘Enrollment declines are everywhere’

In an October paper, Brookings researchers found that over a four-year period that includes the pandemic, about 12% of elementary schools and 9% of middle schools lost at least one-fifth of their enrollment. At The 74’s request, they expanded that data to include all 4,428 schools in the country that reached or exceeded a 20% decline.

The results were sobering: “Enrollment declines are everywhere,” said Sofoklis Goulas, a fellow at Brookings.

In the years leading up to COVID lockdowns, fewer than 2,000 of the nation’s roughly 98,000 schools saw decreases on the level of Jackson. That number more than doubled between 2019 and 2021.

Among districts with over 50,000 students, those with the greatest share of schools that declined by 20% or more are concentrated in the South. They include Memphis-Shelby in Tennessee, the Dekalb County schools near Atlanta, and several in Texas. Other large and mid-size districts topping the list include Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Albuquerque, and the Granite Public Schools in Utah.

A shorter student roster each year might not make headlines, but it could serve as a harbinger of things to come, Goulas said. Administrators in shrinking schools often must merge classrooms, eliminate jobs or rely on donations to save popular sports or music programs.

“The first place where these logistical and financial pressures will show up is the school,” he said.

Many of those facing such pressures are clustered in some of the nation’s largest districts, among them:

- Clark County, Nevada, where 33 of its more than 300 schools, most of them elementary, saw a 20% loss between 2019 and 2021. Further declines last school year translated to a nearly $33 million reduction in state funds.

- Tucson, Arizona, where 15% of its 82 schools lost a fifth or more of their students. Observers say the state’s robust school choice climate is a contributing factor.

- Kansas City, Missouri, which closed two elementary schools last school year, one of which saw at least a 20% drop in enrollment after the pandemic. Five more schools have seen similar declines.

![]()

Leah Russin // The 74

‘The future is uncertain’

photo of Leo Russin

Because of its size, California has the most schools where enrollment loss hit at least 20% during the pandemic — over 1,400. High-priced areas like Silicon Valley reflect a host of recent demographic trends, including record-low birth rates and a limited housing market. Other families left districts during school closures for private schools and charters. All of these factors add up to fewer school-age children attending traditional public schools.

“I think a lot of coastal California looks like this,” said Todd Collins, a school board member in the Palo Alto Unified system.

In small schools, even a slight change in staffing or enrollment can be disruptive. Leah Russin’s son Leo (pictured above on his first day of fourth grade) began the year in a combined fourth-fifth grade class at Barron Park Elementary in the Palo Alto district because there weren’t enough students for two classrooms.

Two weeks into the school year, the 230-student school added a teacher and Leo changed classes.

Russin said despite the staff’s “incredible shuffling and gymnastics,” the instability was stressful. When Leo’s teacher assigned a nonfiction essay, “he wrote about the anxiety of not knowing if his friends were going to be in his class and if he was going to like his teacher.”

Russin and other parents have written letters to the school board advocating for at least two classrooms per grade, even if classes are small.

“We know that means more dollars per student,” she said. “But we believe that means that you are just giving our kids equal opportunity to access the education that kids in a more stable school get.”

Despite the enrollment decline, Collins said the district isn’t planning imminent closures and hopes city planners’ proposals for more affordable housing become a reality, drawing in more families.

“The future is uncertain,” he said. “The current trend is clearly down, but that could change quickly.”

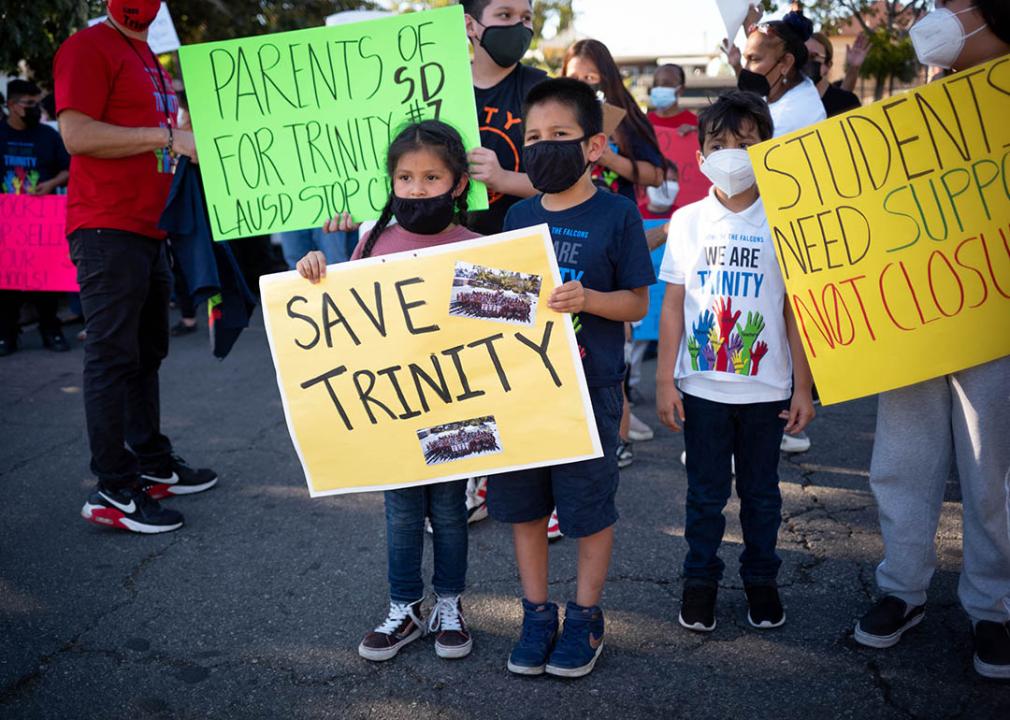

David Crane // MediaNews Group/Los Angeles Daily News via Getty Images

Multi-unit housing restrictions are one underlying threat to school districts

Parents, teachers and students rallied outside a Los Angeles district office in 2021 to keep Trinity Elementary open.

Plans to build apartments near single-family homes often draw strong opposition from residents worried about traffic and property values. Last year, a developer proposed to demolish an old boutique hotel in Barron Park and put up a six-story complex. But the neighborhood association complained it would be too big and the city council said it would likely reject the plan. In hopes of winning approval, the developer has since revised the project to offer a mixture of apartments, townhomes, and hotel rooms.

Restricting multi-family housing to particular zones “makes the city more segregated and separated,” Russin said. “I’m one of the people who strongly advocates for more housing at every income level.”

About a half hour away, the Cupertino district isn’t waiting for families to return. The board closed three schools at the end of last school year.

Many districts with declining enrollment have been able to delay closures by relying on federal relief funds to offset the loss in state funding. Some states have also used that money to lure back students who stopped attending during the pandemic.

Washington state officials, for example, put nearly $5 million toward reaching students who had become “completely disengaged” from school. In December, Superintendent Chris Reykdal credited the program with contributing to a small increase of 2,000 students statewide.

But even with the uptick, statewide enrollment languishes below pre-pandemic levels. “The scariest part is that there’s really no light on the horizon,” Eschbacher said.

If a bright spot is to be found, he said, it could be that “districts are getting better at talking about this.”

He pointed to Indianapolis and Colorado’s Jeffco Public Schools — both of which recently closed multiple schools — as examples of how to communicate “the student experience.”

Rather than overwhelming parents with statistics about deficits and cost-effectiveness, he said, leaders in both districts cited tangible examples of how enrollment loss robs students of a well-rounded education.

“Big schools get advanced courses and small schools don’t,” he said. “Big schools get art and music full time and small schools don’t.”

Brooke Floyd // The 74

‘Center of our neighborhoods’

Brooke Floyd and children, they attend a school in Jackson

But even the most clearly articulated plans won’t keep closures from being a bitter pill for most parents to swallow.

It can be particularly tough for those with close ties to the institutions. “We’re the South. The center of our neighborhoods are churches and schools,” said Brooke Floyd, who leads a nonprofit community organization in Jackson. (Floyd is pictured above with her two children, both of whom attend a Montessori school in Jackson that will likely absorb some of the students from schools that are closing.)

Research shows that high-poverty, minority neighborhoods like those in Jackson are more affected by the decline — and eventual school closures — than those in middle-class communities. Goulas, from Brookings, found that enrollment was more likely to bounce back at schools serving well-off families, while the numbers continued to drop at those with higher poverty.

For Floyd, it’s personal. Chastain Middle School, where she attended as a student, is one of the 13 schools closing. Oak Forest Elementary, where she taught third grade until 2017, was on the chopping block until community members pushed back.

Leaders announcing closures often talk about “reimagining” schools — or, as Greene labeled his plan in Jackson, “optimizing for equity.” But Floyd said parents should make sure the district follows through.

“If that’s what they’re going to push toward us, then we’re going to have to hold them accountable,” she said. “We’re going to have to remind them they promised that our schools were about to be amazing.”

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.