Students with disabilities are referred to law enforcement twice as often as their peers

Photo illustration by Stacker // Shutterstock

Students with disabilities are referred to law enforcement twice as often as their peers

Diptych showing cropped police officer and students walking in school corridor.

Armed police officers are present in more than half of the country’s public schools, and they’re twice as likely to take disciplinary action against students with disabilities than those without, according to the latest federal data.

The disparity has been a contributing factor in attempts to reform the role on-campus police play in the public school system. In February 2024, for instance, Minnesota held a special legislative session examining physical restraint tactics used on students by school police officers, resulting in the implementation of new requirements for specialized training.

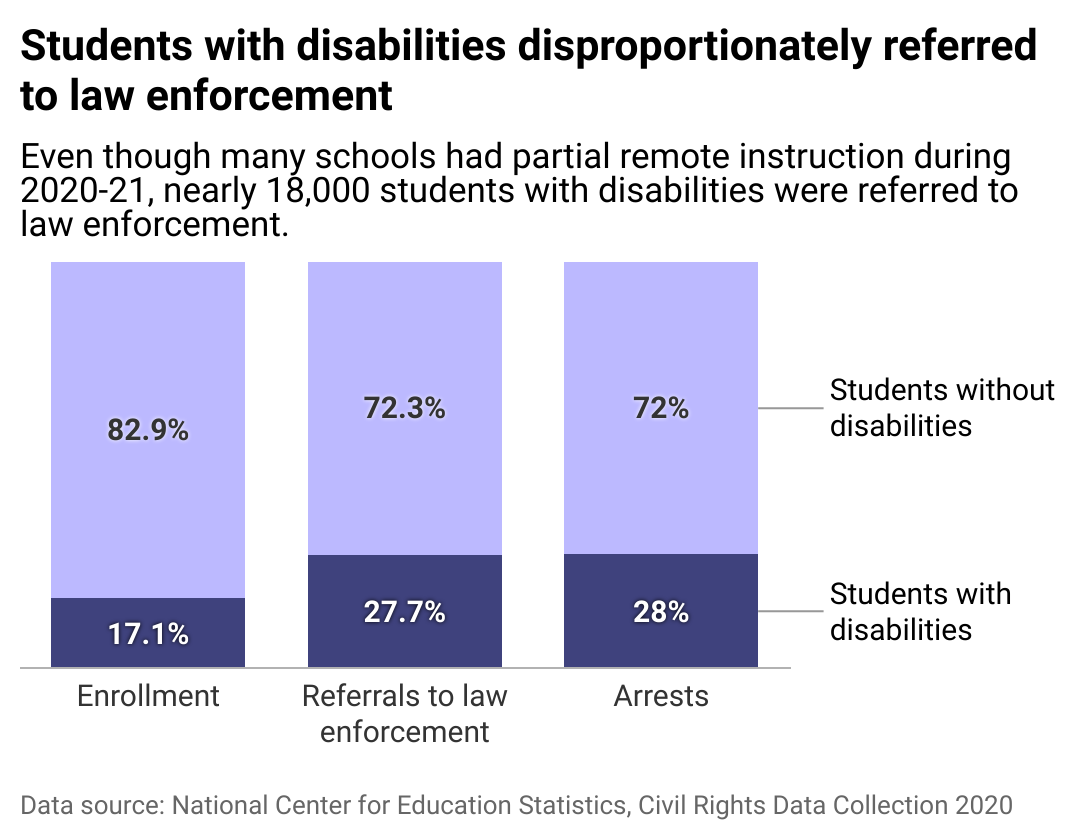

Marker Learning used data from the National Center for Education Statistics Civil Rights Data Collection for the 2020-21 school year to examine the rates of school-related arrests and referrals to law enforcement for students with disabilities compared to those without.

Students with disabilities live with a wide range of conditions that qualify them for special assistance under federal law. Those conditions include specific disorders like ADHD and learning disabilities like dyslexia, deafness and low vision, autism spectrum disorder, developmental delays, and intellectual disabilities.

“Some students with disabilities can have trouble processing or reacting to situations appropriately,” Lateshia Woodley, Kansas City Public Schools assistant superintendent of student support, told The Kansas City Beacon. What can present as insubordination is sometimes just a child’s way of communicating, especially if they feel cornered.

Disproportionate, unhelpful disciplinary actions in schools

According to the Department of Education, a referral to law enforcement by a school teacher or administrator can result in the student receiving a citation, a ticket, a court referral, or a school-related arrest. Students can receive a school-related arrest for misconduct on school grounds, on school transportation, or at a school-related event off campus.

Legal advocates for students with disabilities have argued that police officers interact with students in a way that doesn’t meet the needs of this population, introducing force when demands to follow the rules aren’t met. Police officers also bring onto school campuses a history of systemic bias against Black students, a pattern reflected in school referral and arrest data.

In schools with dedicated police officers, often referred to as student resource officers or SROs, students can find themselves handcuffed by an armed officer over accusations of physical altercations or misbehavior on campus. Students arrested this way are commonly cited for disorderly conduct, such as creating a public disturbance or causing public harm.

These incidents can result in trauma and even physical harm for students with disabilities, as a court recently found in Riverside, California, where the Moreno Valley Unified School District’s policing program was found to be in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The lawsuit was filed in reaction to police officers who repeatedly tackled and then handcuffed a 70-pound, 10-year-old Black boy who exhibited behaviors consistent with his disabilities.

During the 2020-21 school year, school systems in some states moved to reduce the presence of SROs, or else remove them from schools entirely, as part of a nationwide pushback against police brutality. The effort was short-lived, as some schools have returned to using on-campus police in the face of an increasing number of school shootings.

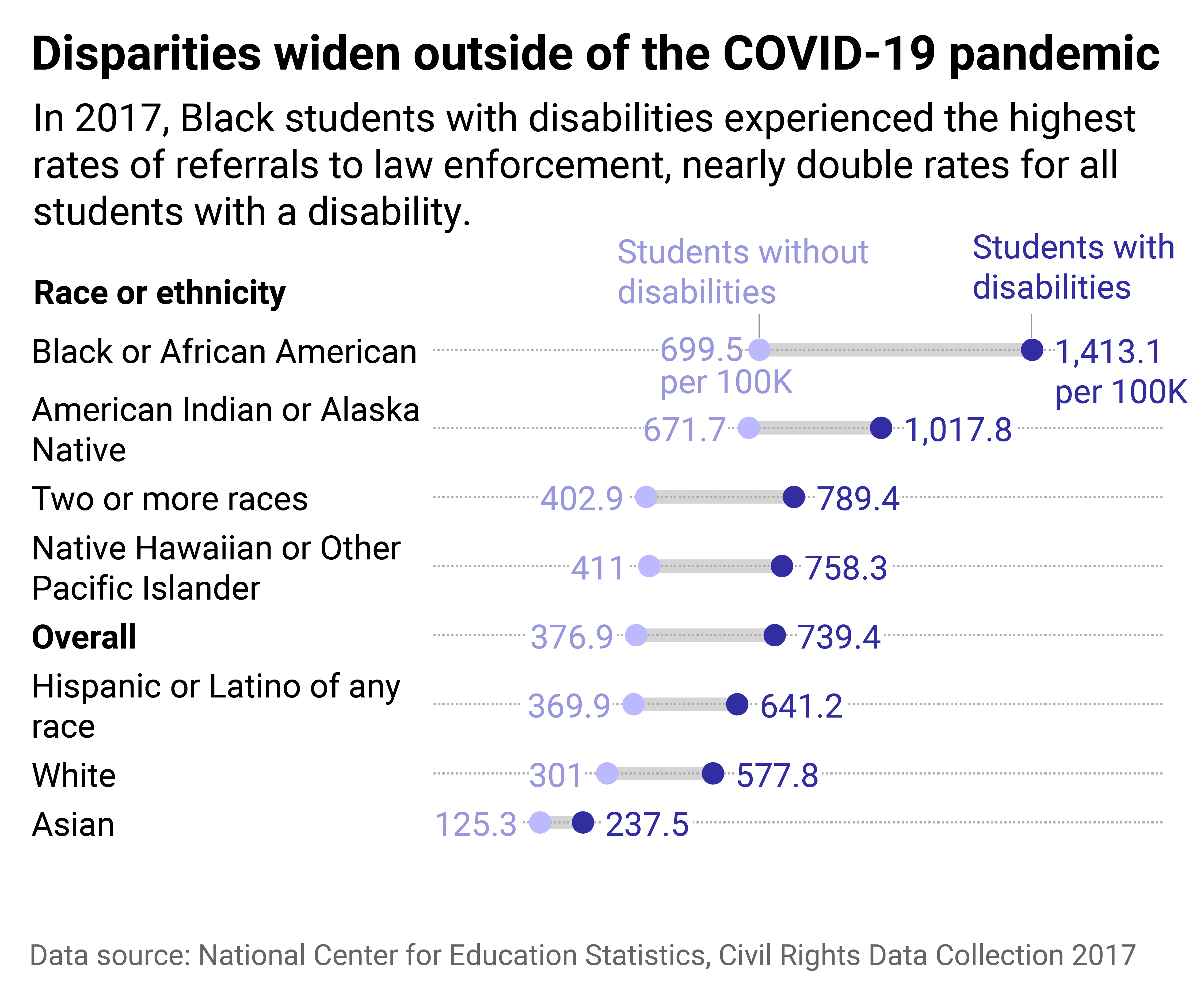

That same school year, 14% of referrals to law enforcement resulted in a school-related arrest. NCES data shows that these arrests happen more frequently to Black students with disabilities than to their white peers.

![]()

Marker Learning

The COVID-19 pandemic suppressed the number of students arrested and referred to law enforcement

Column chart showing students with disabilities were more often referred to law enforcement and arrested, even during the pandemic. As many schools had partial remote instruction during 2020-21, nearly 18,000 students with disabilities were referred to law enforcement.

In general, students with disabilities are referred to the police and arrested at a disproportionate rate compared to their peers without disabilities.

In 2020, the latest school year for which data is available, the number of students with disabilities referred to law enforcement declined compared to previous years tracked by NCES as school closures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic kept students at home. The rate at which students with disabilities were referred or arrested, however, remained similar to rates seen in the 2017-18 school year, suggesting a persistent disparity.

In some instances, schools have been reported to favor referring children with disabilities to police for misbehavior in place of less traumatic interventions. This pattern has become more prevalent as funding for public schools has consistently decreased and schools nationwide experience a shortage of inclusive education teachers—and teachers generally.

Marker Learning

Disparities for students with disabilities intersect with race

Range plot showing students with disabilities are more often referred to law enforcement across every race and ethnicity. Black students with disabilities experienced the highest rates of referrals to law enforcement, nearly double the overall average.

Studies have demonstrated that Black children are no more likely to misbehave than kids from other racial backgrounds, but they are penalized for their behavior at a higher rate—especially Black children with disabilities—a disparity that has drawn bipartisan condemnation.

Some have warned that having police officers in schools may cause more harm than good. A 2018 study by the Texas Education Research Center found that Texas experienced lower high school graduation and college enrollment rates following increased police presence in its public schools. In lieu of police referrals, the American Civil Liberties Union has urged schools to handle student altercations and events that rise to the level of disorderly conduct with alternative methods that are less harmful to students.

A number of states have made efforts to redress disparities within law enforcement referrals and on-campus arrests. Dallas public schools, for instance, have discussed reallocating funding toward hiring more school counselors, in hopes of preemptively addressing behavioral problems before they would require further intervention. In Nashville, Tennessee, public school administrators have found success in placing officers on patrol outside elementary schools and staffing “safety ambassadors” inside in their place. These efforts reduced student arrests by 70% for children 12 years and under.

Still, the onus may be on individual states to pursue new solutions in the face of the disparate treatment students with disabilities receive from school police officers. Proposed federal legislation backed by the ACLU that would’ve diverted money for school police toward funding more school counselors in 2022 has struggled to gain enough congressional support to enact it into law.

This story originally appeared on Marker Learning and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.