Post childbirth without paid leave, teachers leave their own children to teach others'

Eamonn Fitzmaurice // The 74

Post childbirth without paid leave, teachers leave their own children to teach others’

A custom illustration of an adult hand reaching one of a baby’s with pink and green backgrounds.

When elementary school teacher Kimberly Papa gave birth to her daughter, Margot, a little over a year ago, she wasn’t expecting much in the way of paid maternity leave. She knew that the majority of Americans don’t have access to it and certainly not those in her state of Ohio.

As reported by The 74, while she could take 12 weeks off through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, this only guaranteed her job security — not pay — and her family couldn’t afford to miss out on months of her salary.

“Obviously if I didn’t have those paychecks, I wouldn’t have been able to pay my mortgage or pay for groceries or anything like that. Put gas in my car to go to doctors’ appointments,” the music teacher said on a recent phone call, baby Margot cooing and spilling Cheerios in the background.

Teachers in her district can get paid for those 12 weeks if they’ve accrued enough sick days, but as a career changer, Papa only had four weeks banked. Even before her unexpected C-section and health complications related to an autoimmune disorder, she knew that wouldn’t be enough time.

There was one workaround, though: In Papa’s district, teachers are allowed to donate up to five of their sick days to colleagues in need. A teacher at her school distributed a link — much like a GoFundMe page — and was ultimately able to raise the remaining 30-or-so days.

Without clear confirmation from HR on just how many paid days she had, she gave birth trusting that her colleagues’ donated ones would come through.

Papa is one of many public school teachers forced to scrimp and save sick days, pay for their own substitute teachers, go without pay or perfectly time their pregnancies to align with summer break in order to care for their babies and recover. Many end up returning to the classroom before they’re ready, sometimes as early as three weeks after giving birth.

While it is difficult to pin down an exact figure, as of 2022, 18% of the largest school districts in the country provided paid parental leave beyond sick days to public school teachers, according to a National Council on Teacher Quality report. For those that do, the amount of leave offered varies widely, ranging from one day to five months, with most districts offering less than 31 days— all at varying levels of pay and with differing eligibility.

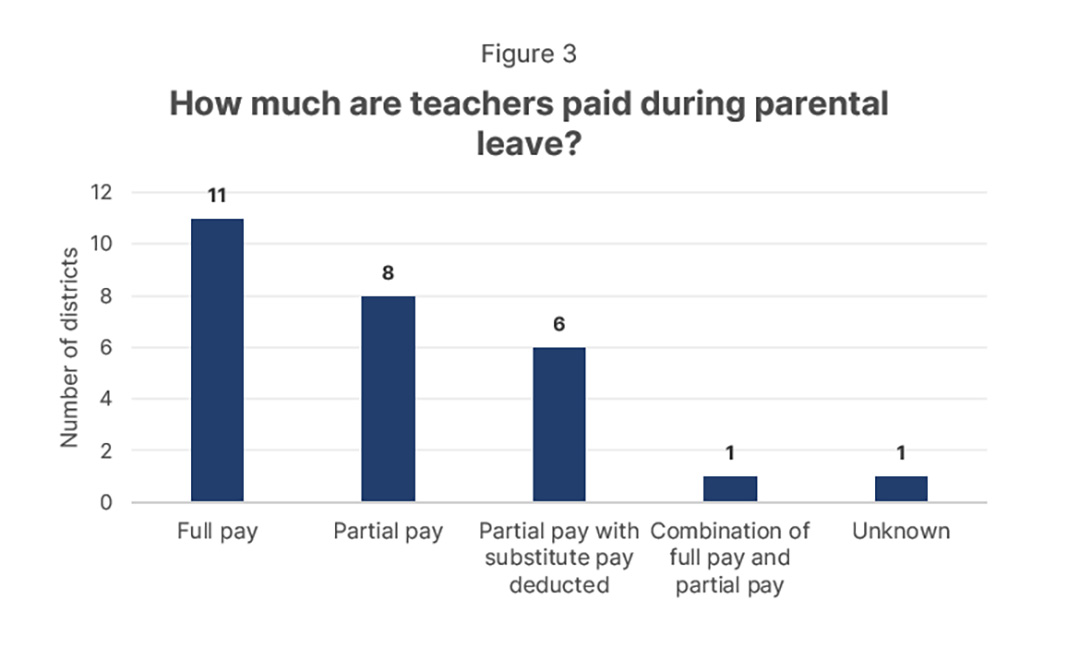

Most teachers receive an average of 10-14 sick days a year, according to NCTQ, and many districts require that they exhaust all their accumulated sick time before they can access paid leave. And some go even further: seven of the districts subtract the cost of a substitute from the teachers’ paychecks during their time on leave, effectively getting them to pay for their own coverage.

![]()

National Council on Teacher Quality 2022 Report

Few school districts offer dedicated paid parental leave

Chart showing how much teachers are paid during parental leave.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the share of state and local government workers in elementary and secondary schools that have access to paid family leave is 28% — significantly higher than NCTQ’s figure — though this includes all school-based occupations, including superintendents and principals. An internal 2019 survey conducted by the American Federation of Teachers of about 50 district contracts found that only about 10% offered dedicated paid parental leave. Most districts relied on a sick day accrual system that disadvantages younger teachers, who likely have the least banked time and the greatest need for parental leave, according to an AFT spokesperson.

“Teachers, for the most part, are women and mothers,” said Ashley Jochim, a freelance education researcher and consulting principal at Arizona State University’s Center on Reinventing Public Education. “And so the fact that there is sort of an inattention to these issues around parent leave is startling.”

In the 2020-21 school year, there were 3.8 million full- and part-time public school teachers, 77% of whom were women and a majority of whom were of childbearing age. About half — 48% — of all public school teachers have children living at home, according to an analysis of data spanning 2012-16 by the Brookings Institution’s Michael Hansen and Diana Quintero.

The National Council on Teacher Quality analyzed 148 school districts in the U.S., including the 100 largest as well as the largest in each state, and found that 18% offered paid parental leave beyond sick days. Though a few of these districts fall in states that offer paid leave, the organization said it’s not confident that schools are necessarily following state policy.

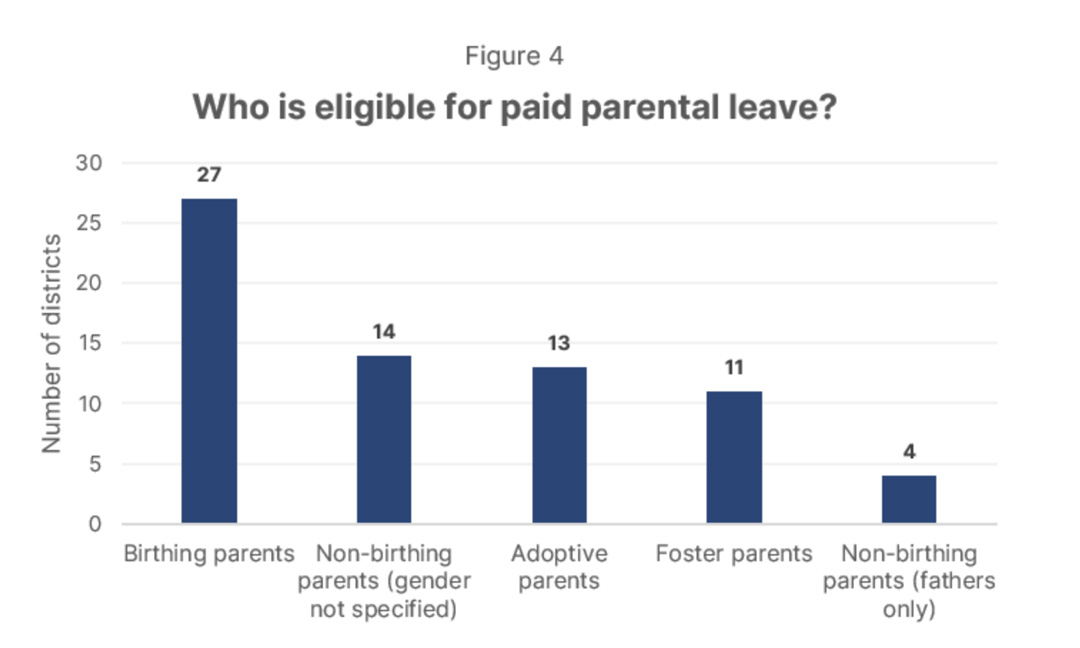

National Council on Teacher Quality 2022 Report

Those eligible for paid parental leave differs throughout U.S. school districts

Chart showing who is eligible for paid parental leave.

Of the analyzed districts, 27 offer paid leave for a birthing parent and 18 offer some amount to fathers or non-birthing parents. Eleven districts offer all days at full pay, while 15 offer partial pay. Thirteen districts provide some leave for adoption.

Teachers across the country, like Papa, know the struggles associated with these patchwork policies. But those outside the classroom are often surprised to learn the lengths to which teachers must go, according to various experts. There’s a general understanding that though teacher pay may lag, the fringe benefits are often much more robust than what you’d see in the private sector, leading to a misperception that paid parental leave is included, said Jochim.

“Parental leave shouldn’t feel like a miracle,” wrote AFT President Randi Weingarten in a statement to The 74. “It should be a basic benefit that school districts and states offer to all employees.”

This system exists against the backdrop of a maternal health crisis, particularly stark for mothers of color and worsened by the pandemic. Amid record high teacher turnover, a shortage of substitute teachers, and wide support for paid parental leave policies nationally, experts note that family leave could be an important recruitment and retention tool— especially for female teachers of color, who are underrepresented in the field. About 79% of public school teachers are white, 9% are Hispanic and 7% are Black, according to the most recent U.S. Department of Education data.

There’s a clear cost to school communities — particularly students — anytime a teacher is gone for an extended period, said NCTQ President Heather Peske, but “I also think that we can’t ask teachers to sacrifice having children of their own in order to teach ours. It’s just not right and not fair.” And often teachers are asked to return to the classroom far earlier than the International Labor Organization‘s 18-week recommendation.

In August 2023, Papa, the music teacher, returned to work, grateful her coworkers’ donated time had allowed her to take a paid maternity leave, but anxious that she was beginning a new school year with a 6-month-old baby and a completely drained bank of sick days.

She tried to schedule her baby’s doctor appointments before or after the school day, but that wasn’t always possible. She said she felt guilty anytime she had to leave early or take time away for her kid, putting more work on her colleagues in the throes of staffing shortages. On days she was sick or exhausted from being up all night with a newborn, she forced herself to push through, not wanting to burden others and not able to afford the unpaid time, a common refrain heard among teachers who are also parents.

Because of the fragile nature of schools, it’s treated as shameful when a teacher needs to be absent, even when it’s to care for a sick child, said Jochim, the researcher who works with CRPE. But, she added, “Nobody’s really asking themselves … ‘Why did we design the system in a way that can’t be resilient in the face of caregiving responsibilities that women bear most of the burden of?'”

One day, Papa’s daughter had an allergic reaction and was rushed to the emergency room. Papa said she found herself sitting there, thinking, “‘Oh my God, am I not able to go to work tomorrow?’ And it’s so awful to think that. Here I am, rushing my child, my baby to the ER. She’s got hives on her face … and my thought is, ‘What am I going to do about work tomorrow if I can’t go in?'”

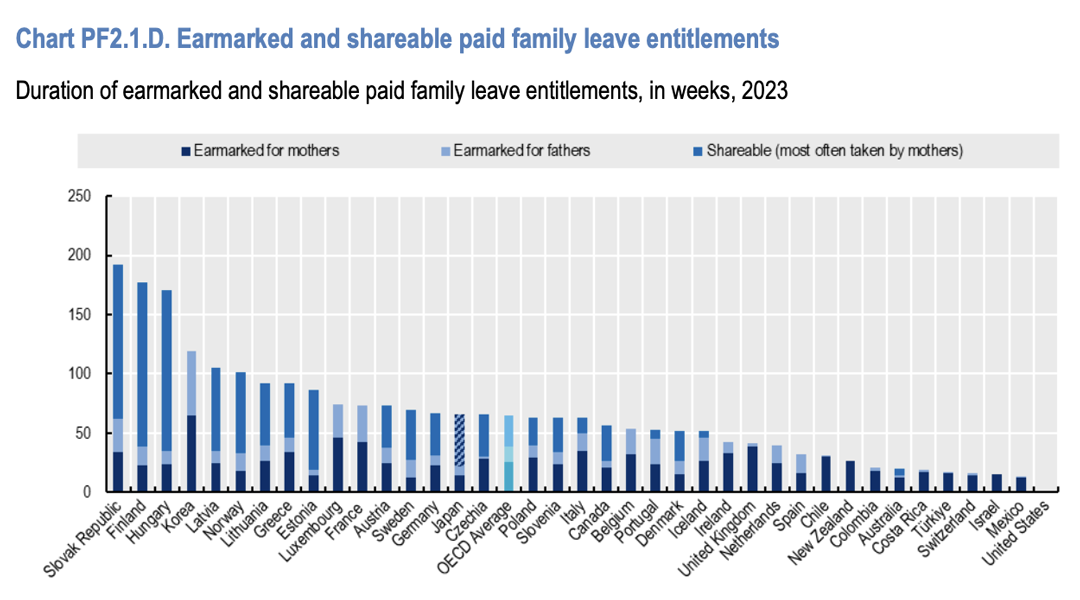

OECD Family Database

Not just teachers

Chart showing earmarked and shareable paid family leave.

The United States is the only country that does not mandate any paid leave for new parents, among the almost 40 nations included in The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development , according to data compiled by the organization. The smallest amount of paid leave required in any of the other nations, including the United Kingdom and Canada, is about two months, marking the United States as a major outlier.

Despite 74% of workers reporting that it’s either extremely or very important for them to have a job that offers paid parental, family or medical leave, currently only 13 states and Washington, D.C. mandate paid parental leave, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center. An additional eight have voluntary systems that rely on private insurance. But not all of these include public employees, such as teachers. For example, in the early 2000s, California became the first state to pass a paid family leave policy, but as state employees, teachers were not automatically included.

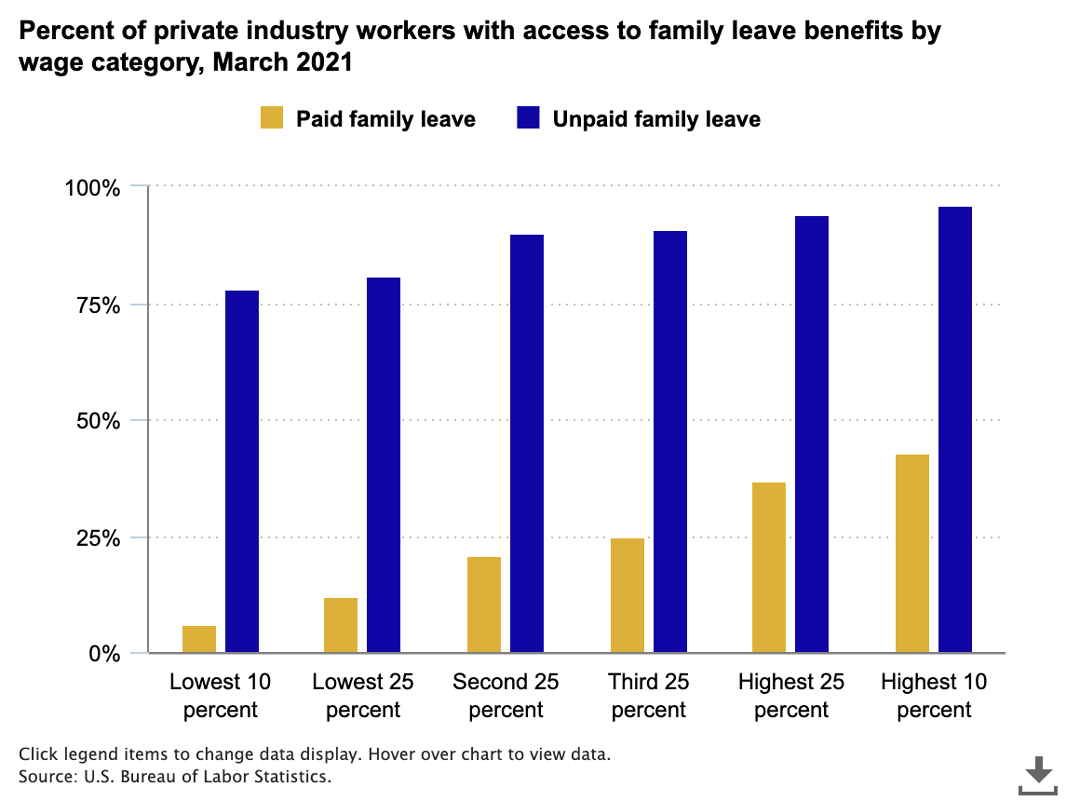

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Inverse relationship exists with income and access to paid leave between public and private workers

Graph showing results of “Percent of private industry workers with access to family leave benefits”.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, on average teachers fare about the same as all civilian workers, 27% of whom have access to paid family leave. That number rapidly climbs, though, for public and private workers in management, professional, and related occupations — 39% of whom receive the benefit — and private industry workers in finance and insurance — 57% of whom do. Generally, there’s an inverse relationship between income and access to paid leave: among the lowest 10% of earners, only 6% had access.

The economic argument that paid parental leave is too expensive to fund — either through the government or private industry — doesn’t properly account for what it costs not to offer it, said Peske. “Given how much time it takes to recruit and hire a new teacher and inject that new teacher into the school, you really want to consider parental leave policies and figure out how you can afford [them],” she said. “Because it’s so much more costly to lose a really strong, good teacher than it would be to pay for the parental leave.”

Katherine Bishop, president of the Oklahoma Education Association, said educators in their family-building years are frequently in their first five years of teaching — when most leave the profession.

Oklahoma is one of at least three states — including Tennessee and South Carolina — to enact paid parental leave policies for teachers over the last year, along with the nation’s fourth-largest school system, Chicago Public Schools. In 2018, New York City, the country’s largest district, rolled out six weeks of paid leave at full salary for mothers, fathers, and foster parents after a petition garnered 85,000 teacher signatures.

“In an era where our educators are feeling so disrespected, it is bills like this that give our worth and dignity back and that we are seen as the professionals that we are,” said Bishop, whose state whittled the initially proposed 12-week paid leave down to six. “I think that is so important for people to understand.”

‘There’s no one to help me out’

By the time Jeremy Hight and his wife had their first child in 2019, he had been teaching at a small, rural public school in Nevada for over a decade and had accrued 110 sick days — the equivalent of 22 months.

Yet, when his wife gave birth, his district would only allow him to take four weeks off paid, he said. At the time, regardless of how many sick days a teacher had banked, only 20 could be used for paternity leave. He could take an additional two months through FMLA, but they would be unpaid, which Hight’s family couldn’t afford.

So, four weeks after his wife’s emergency C-section he returned to the classroom.

“It was painful for her,” he said. “For me it was emotionally painful just to not be able to be there and help out my wife. She did have some family nearby but not anybody who could get there and help her to stand up, help her to move around as easily as she could. Or just to put the baby down in a crib very easily. She couldn’t bend over to put the baby down very well. Having to leave after a month — four weeks — was just heartbreaking.”

Despite the challenges, he recognized he was lucky to even have those 20 days set aside in the first place. He said for an early career teacher, that kind of time with their family would be out of reach.

While some may conceive of parental leave policies as relevant only to the person who gives birth, Ruth Martin, senior vice president of advocacy group MomsRising, said it’s important for policies to incorporate men and non-birthing parents. When dads are able to access paid time away from work they feel more bonded to their child, she said, and are more likely to play a larger role in the household labor that is unpaid, time-consuming and typically left for women.

Since then Hight’s district has updated its contract, allowing fathers to take six weeks off paid and mothers to take eight — but only if they have the sick days banked.

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.