21 of the most impactful intelligence leaks in US history

Handout // Getty Images

21 of the most impactful intelligence leaks in US history

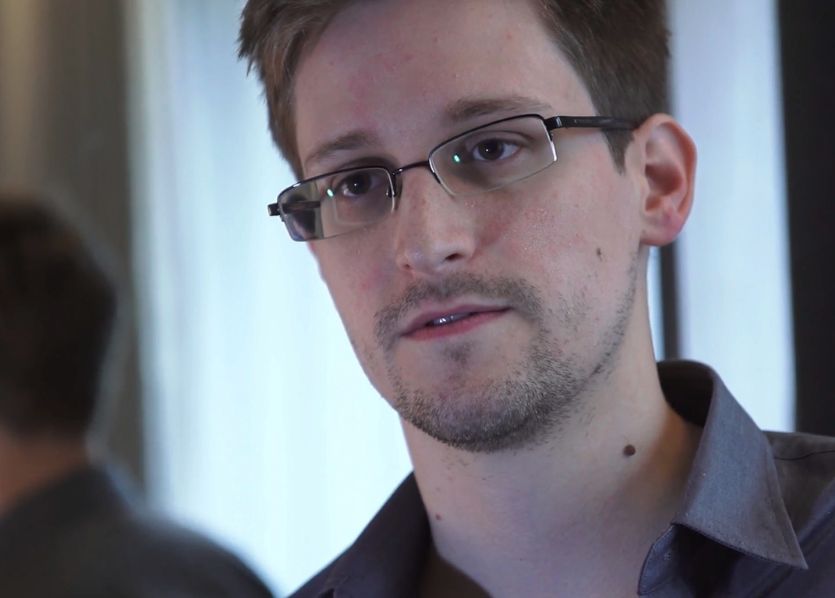

Edward Snowden speaking to The Guardian.

In April 2023, Massachusetts Air National Guardsman Jack Teixeira was arrested and charged in connection with a leak of classified U.S. intelligence documents linked to the Pentagon. On May 19, a federal judge ruled that while Teixeira awaits trial, which could potentially land him decades behind bars, he will remain in federal custody. Further recent reports have indicated that Teixeira’s anti-government actions were motivated by a deeply racist and bigoted worldview.

The hunt for Teixeira reawakened the American public’s consciousness around intelligence leaks and spurred conversation around the digital nature of the breach. The documents, shared in a Discord server, had been online for nearly a month before U.S. intelligence agencies became aware of them. This has already led the Biden administration to reduce the number of people who have access to classified documents and will certainly lead to further changes.

Far from a unique phenomenon, intelligence leaks have a long history in the U.S. The practice of sharing information about the inner workings of government institutions or companies is commonly known as “whistleblowing.” Defined by the Director of National Intelligence as “the lawful disclosure of information a discloser reasonably believes evidences wrongdoing to an authorized recipient,” whistleblowing is rarely, though occasionally, rewarded.

The Securities and Exchange Commission, for instance, recently issued a $279 million reward to a whistleblower for information that aided the agency in enforcing its ability to regulate the securities market. Of course, not all information leaks are considered rightful, and despite what light such leaks bring to the most interior actions of the U.S. government, many are actionable, resulting in financial penalties and prison sentences for those involved.

To provide a historical perspective on whistleblowing and intelligence leaks, Stacker compiled 21 of the most impactful intelligence leaks in U.S. history from historical archives, government reports, and federal agencies.

![]()

MPI // Getty Images

The Hutchinson Letters (1772)

A portrait of Thomas Hutchinson.

The earliest substantial information leak in American history, the Hutchinson Letters, also played a small part in the nation’s founding. In 1772, Benjamin Franklin—at the time employed by the British as postmaster general for the Crown in London—came into the possession of letters from Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, urging the British to increase its military presence in the colonies in order to suppress colonial rebels.

Franklin secretly distributed the documents to his fellow revolutionaries. When John Adams made the documents public in 1773, Hutchinson fled the colonies to escape the wrath of enraged Bostonians. Three innocent men were accused of the affair, prompting Franklin to come forward as the disseminator of the letters, for which he was dismissed from his position as postmaster general. Franklin returned to America in 1775, soon after helping to draft the Declaration of Independence.

Historical // Getty Images

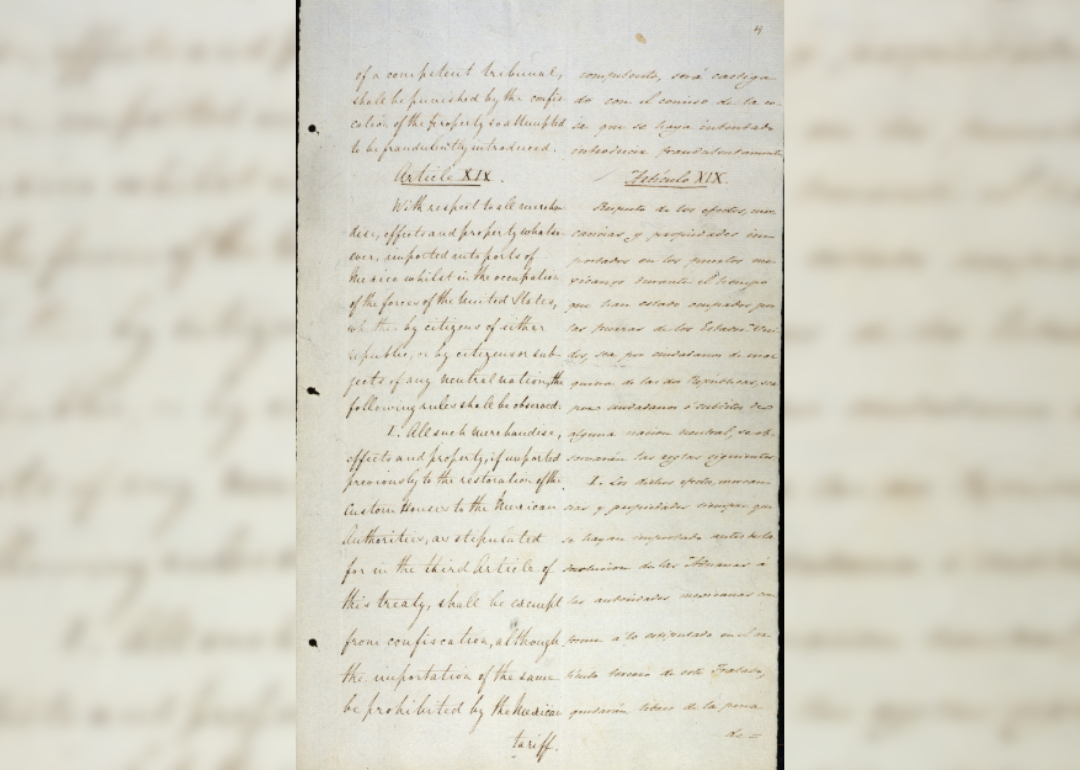

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)

A page from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

In 1848, Irish immigrant John Nugent published the unsigned Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in the New York Herald ahead of its formal signing. The treaty, which would bring the yearslong Mexican-American War to an end, also established large territorial gains by the United States, including the establishment of the Rio Grande as the U.S.-Mexico border, recognition of the annexation of Texas, the sale of California, and a gain in territory that would eventually become part of Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Nugent was held (comfortably) captive for a month by an infuriated U.S. Senate but did not reveal who his source was. Both the scandal and the fallout of a costly war in part led then-President Polk not to seek a second term. Evidence suggests that future President James Buchanan, who was then serving as secretary of state, may have leaked the treaty to Nugent.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

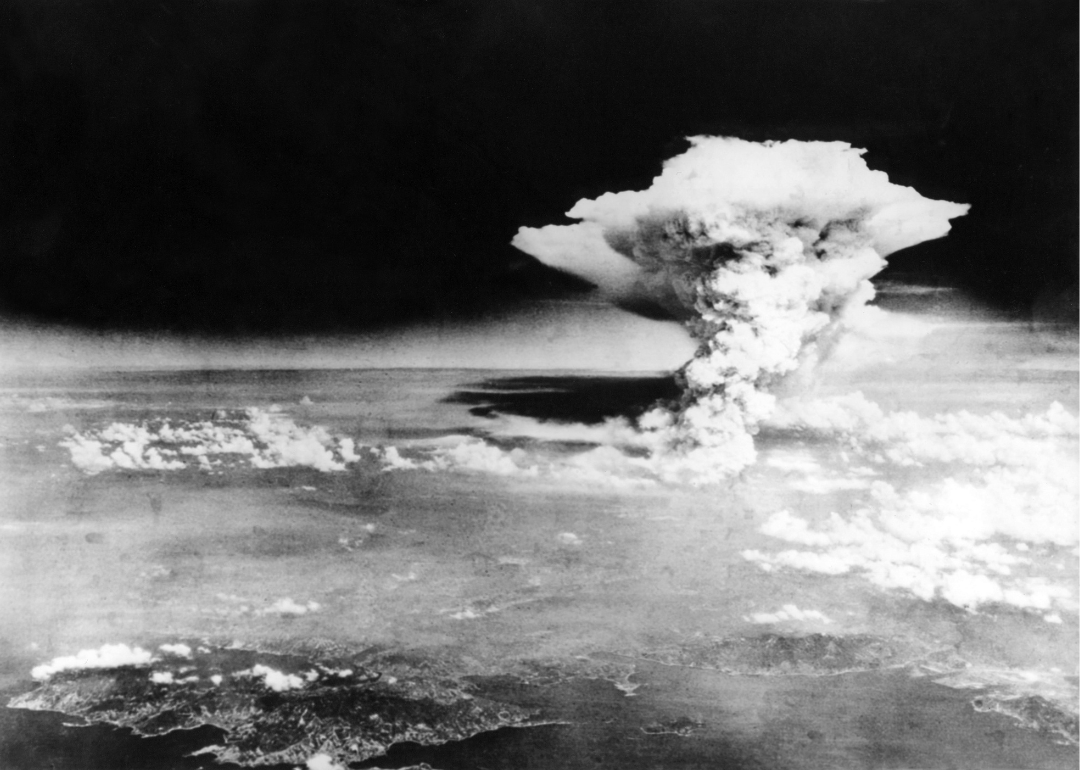

Theft of atomic bomb information (1945)

The nuclear explosion over Hiroshima.

A German physicist who fled Germany in 1933, Klaus Fuchs would go on to become a British subject in 1942 and was subsequently sent to the U.S. to participate in the Manhattan Project. Fuchs had fled Germany as a result of his communist beliefs, and in 1945 during his work on the atomic bomb leaked advanced information on the U.S.-led effort to the Soviets. Eluding suspicion until 1948, Fuchs was eventually captured in England and confessed to the leak. He served a 14-year prison sentence.

Fuchs was apparently driven both by his Soviet sympathies and his belief that the U.S. should not be the sole nation to possess atomic weaponry. After Fuchs’ death in 1988 in East Germany, Edward Teller indicated that the value of the information leaked by him was “not very important” and that the “Russians knew how to build a bomb” without it.

Bettmann // Getty Images

The Pentagon Papers (1971)

Daniel Ellsberg appearing before microphones, surrounded by reporters at the Federal Building.

This report, officially titled “History of U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945–68” and popularized as “The Pentagon Papers,” was provided to The New York Times by Daniel Ellsberg, a strategic analyst for the Rand Corp. who had served in the U.S. Marine Corps and previously supported the war in Vietnam. Containing detailed documentation of the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, the study was commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. It contained compromising proof of the government’s attempts to mislead the American public on key components of the war effort.

The publication of portions of the papers in The New York Times beginning in June 1971 led the Department of Justice to seek a restraining order against the paper, a trial that would eventually make its way to the Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of the Times’ right to publish, solidifying freedom of press protections and opening up the field for other papers to follow in the Times’ wake, most notably The Washington Post. Embarrassed by the leak, the Nixon administration attempted to indict Ellsberg on criminal charges, but the charges were dismissed after prosecutors discovered that a team directed by the White House had broken into Ellsberg’s offices—a precursor to the break-in that led to the Watergate scandal.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Watergate scandal (1972)

Tourists in front of the White House reading newspaper headlines about Nixon resigning.

On June 17, 1972, a break-in took place at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in Washington D.C. Though President Nixon’s involvement in the break-in and subsequent cover-up were reported on by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in The Washington Post throughout 1972, the Nixon administration led a successful public relations campaign to discredit the reporters; Nixon won the 1972 election in a landslide.

A key informant for Woodward and Bernstein was the famously anonymous “Deep Throat,” who later identified himself as Mark Felt, deputy director of the FBI at the time of the scandal. Though he was suffering in the court of public opinion, Nixon’s true downfall would not come until 1974, when a disclosure by former White House staff member Alexander Butterfield revealed that the president secretly recorded all conversations taking place in his offices. Contained within those recordings were instances of Nixon discussing the break-in and cover-up in detail. The revelation of these recordings swiftly led to Nixon resigning the presidency in August 1974, the first and only resignation of a president in U.S. history.

Bettmann // Getty Images

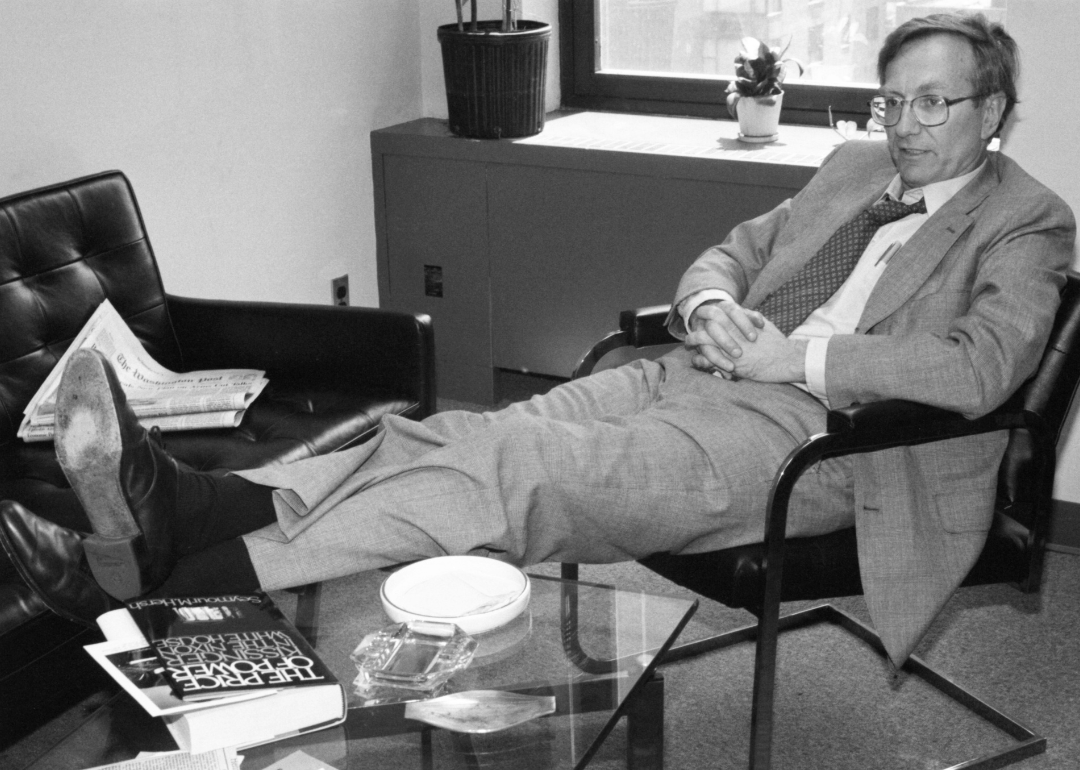

Operation CHAOS whistleblower (1974)

Seymour Hersh, who reported on Operation CHAOS.

In 1974, investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, who also reported on the Watergate scandal, published an explosive series of stories in The New York Times outlining Operation CHAOS, a domestic spying operation that began during Lyndon Johnson’s administration in 1967 and continued during the Nixon administration.

Seeking to tie U.S. citizens involved in the anti-war and Black nationalist movements to foreign influences, the FBI, CIA, and other federal agencies planted agents within these groups to gather information. The reports led to a strong public backlash and a congressional investigation by Senator Frank Church (“the Church Committee”), which laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in 1978.

Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

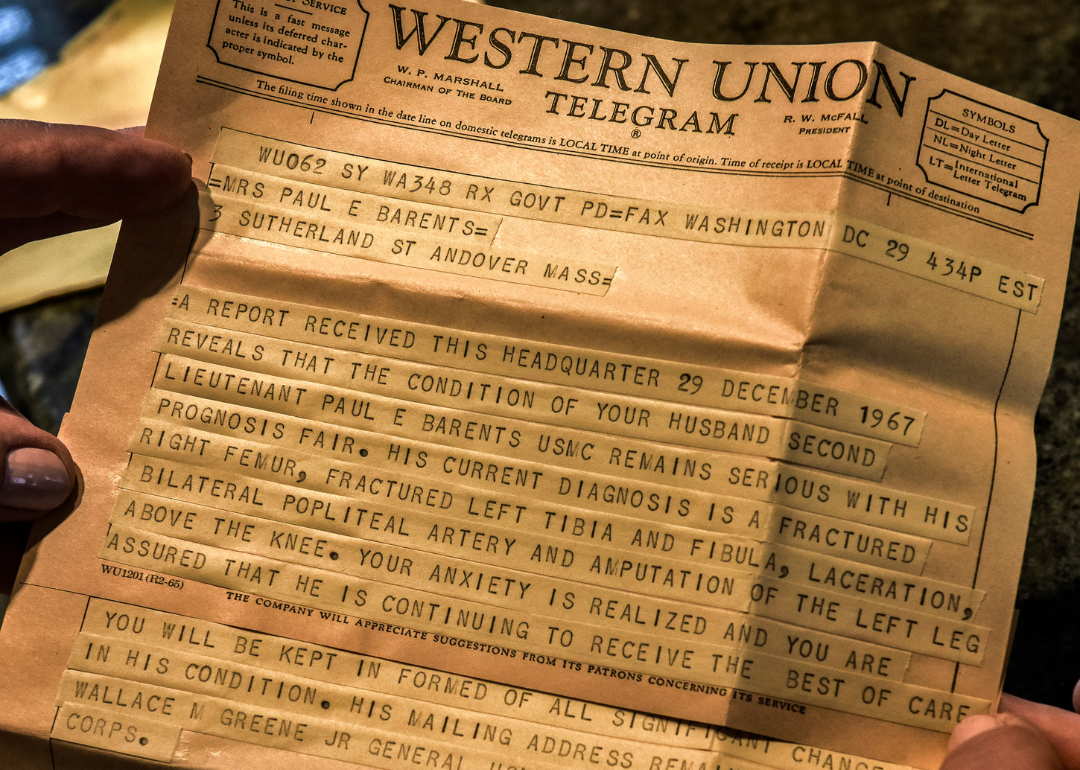

Project SHAMROCK (1975)

A Western Union telegram sent to the mother of a soldier who had been killed in World War II.

Unearthed by L. Britt Snider, a staff member on the Church Committee, Project SHAMROCK was a National Security Agency program that secretly monitored the telegrams of U.S. citizens. As Snider investigated the NSA and met a series of dead ends, he was finally able to meet with former NSA Deputy Director Dr. Louis Tordella, who gave him a full account of the history behind Project SHAMROCK, indicating it had been active since World War II and that the telegram companies involved willingly corporated with the domestic surveillance.

Snider’s report on the program in 1975—which detailed the 150,000 telegrams reviewed by the NSA each month—led to the end of SHAMROCK and the creation of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which placed limitations on the ability of government agencies to spy on U.S. citizens.

Consolidated News Pictures // Getty Images

The Iran-Contra affair (1984)

Former US National Security Advisor Robert C McFarlane testifying before the joint US Senate and US House committee investigating the Iran-Contra Affair on July 14, 1987.

The Iran-Contra affair revolved around a convoluted program of secretly selling U.S. arms to Iran and using the proceeds to secretly fund anti-socialist rebels in Nicaragua in order to sidestep approval by a Democrat-led Congress. Iran was embroiled in a prolonged war with Iraq, meaning the U.S. was officially taking a side in that conflict. First reported in 1986 by the Lebanese newspaper Ash-Shiraa after a cargo plane carrying arms to the rebels was shot down, the reporting on the affair led to the formation of the Tower Commission and the appointment of an independent counsel (Lawrence Walsh) to investigate the affair.

The resulting report led to the resignation or firing of several involved parties in the U.S. government, but a deeper connection within the Reagan administration linking the president to the arms deals was never established. Though the Iran-Contra affair was a significant scandal in its time and left a stain on foreign policy issues in its wake, it did not have quite as profound an impact on American politics as other intelligence leaks. Indeed, Reagan left office with a high approval rating.

PAUL J. RICHARDS // Getty Images

Robert Hanssen, spy (1985)

The identification and business card of former FBI agent Robert Hanssen as seen inside a display case at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia.

Robert Hanssen is a former FBI agent who served as a spy for the Soviet Union beginning in 1985 and continued to do so until his capture in 2001. Providing the Soviets with a laundry list of classified information from nuclear secrets to the identities of KGB double agents, Hanssen’s motivations were entirely monetary, and he received over $1.4 million in compensation for his counterintelligence.

Upon his capture, Hanssen took a plea deal in order to avoid the death penalty and to secure a better future for his wife and children; on 15 counts, he was sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole. Currently serving his sentence at ADX Florence, Colorado, one of the nation’s toughest federal supermax facilities, Hanssen is in solitary confinement 23 hours a day.

LUKE FRAZZA // Getty Images

Aldrich Ames case (1994)

Former senior Central Intelligence Agency office Aldrich Hazen Ames being led from U.S. Federal Courthouse in Alexandria, 22 February 1994, after being arraigned on charges of spying for the former Soviet Union.

Aldrich Ames was a CIA case officer who specialized in Russian intelligence services and counterspied on behalf of the Soviet Union. Ames received an estimated $2.5 million from the Soviets for the information he sold, which included—most controversially—the identities of every U.S. agent operating in the Soviet Union to the KGB. This led to a number of executions of those agents in Moscow, which alerted the CIA to the likelihood of a mole within their agency. Ames was sentenced to life in prison for his espionage and has admitted that his motives were mainly personal greed, but also a disenchantment with the practice of espionage altogether.

Stephen McCarthy // Getty Images

Chelsea Manning leaks (2010)

Chelsea Manning speaking on stage during day one of Web Summit Rio 2023 at Riocentro in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Now one of the most well-known whistleblowers in history, Chelsea Manning was serving as an intelligence analyst in Iraq in 2010 when she downloaded a vast trove of classified documents detailing U.S. foreign political dealings and policies. Releasing information first through WikiLeaks, an organization devoted to revealing secret government information to the public, the documents in Manning’s leak would be published by The Guardian, The New York Times, and Der Spiegel.

Most notably, Manning’s leaks revealed information on U.S. activities in Iraq and Afghanistan that indicated the government had misled the American public about the extent of civilian casualties, which were an estimated 10,000 higher than reported. Manning received a 35-year sentence for her actions but served just seven years after President Obama commuted her sentence in the last days of his presidency.

Handout // Getty Images

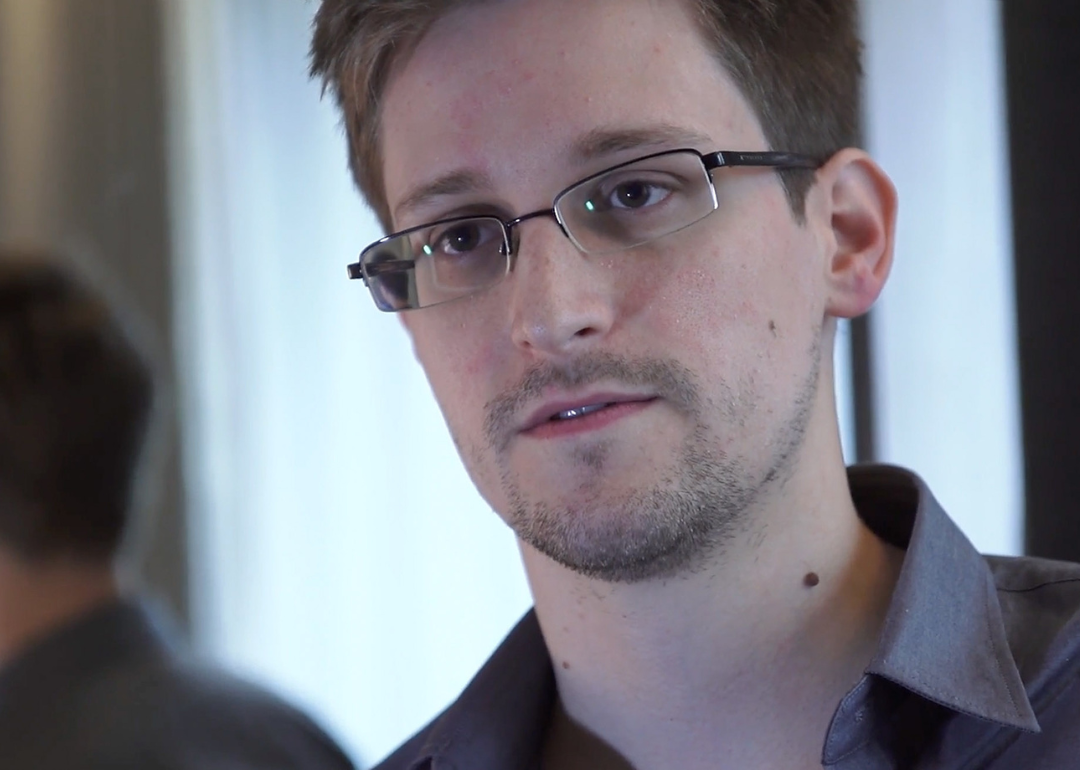

Edward Snowden leaks (2013)

Edward Snowden speaking to The Guardian.

In some ways paralleling the revelation of Project SHAMROCK, Edward Snowden was an NSA private contractor who collected vast quantities of information on the agency’s illegal surveillance programs and released it to The Guardian and The Washington Post. Most significantly, the leak revealed that the NSA had been illegally spying on U.S. citizens by collecting daily phone records from Verizon and through a number of internet services, including Facebook and Google. Further revelations brought to light the worldwide scope of the U.S. spying operation, called PRISM, including the fact that the U.S. directly monitored German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone calls.

A month before leaking the classified information, Snowden had taken medical leave and flown to Hong Kong. Days after he revealed himself as the whistleblower, the Obama administration charged him under the Espionage Act. In order to escape possible extradition from Hong Kong, Snowden sought and was granted asylum in Russia, where he has since become a permanent citizen.

Dan Kitwood // Getty Images

Cover-up of Gulf War syndrome (2013)

Gulf War veterans marching d.uring a protest to mark the 20th anniversary of the end of the Gulf War

A former epidemiologist in the Department of Veterans Affairs, Steven Coughlin testified before Congress that the VA had deliberately manipulated and covered up data around the existence of Gulf War syndrome. Recently understood to have its root causes in exposure to sarin gas, a nerve toxin, Gulf War syndrome was considered a mystery for decades, in part due to inconclusive VA studies. Coughlin indicated that the cover-up had in some cases cost the lives of veterans the department was charged with helping. Though there was little by way of major news coverage of the allegations, Coughlin’s actions appear to have had a minor corrective influence—the department now provides benefits to those who suffer from Gulf War syndrome.

The Washington Post // Getty Images

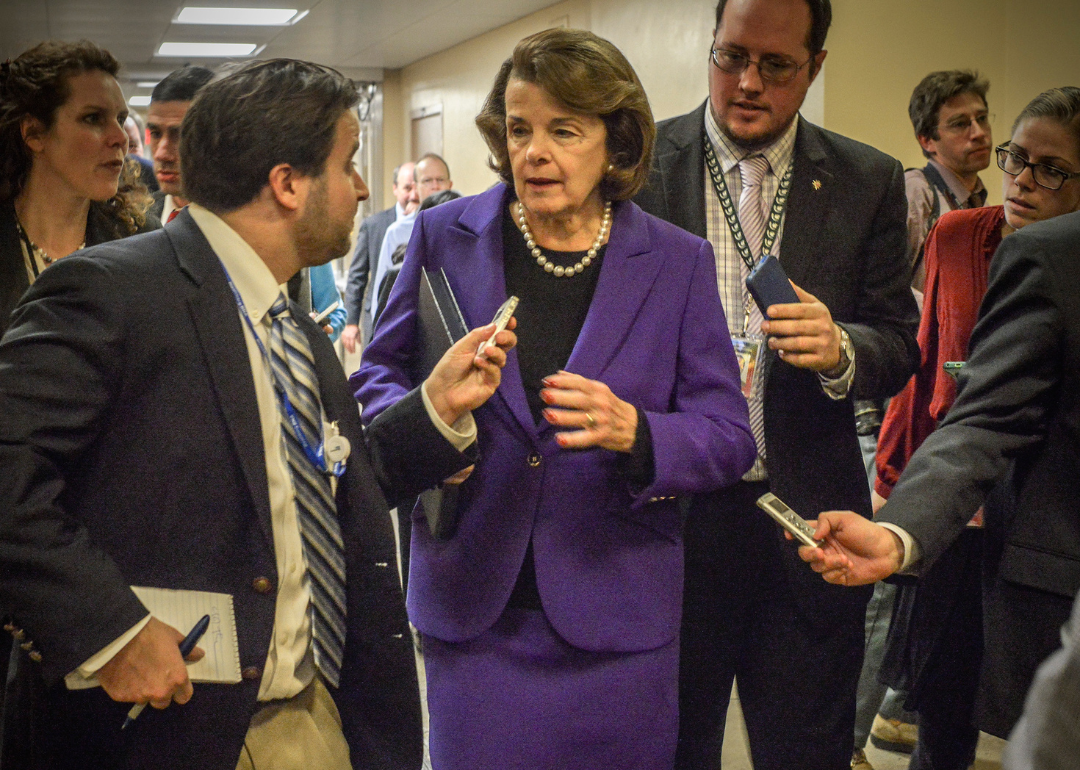

CIA torture report (2014)

Sen. Diane Feinstein making her way through a crush of reporters toward the Senate floor to deliver her remarks on the CIA report on torture released the morning of December 9, 2014.

Detailing the full extent of the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” by the CIA during the early 2000s, the 6,700-page document released by the Senate Intelligence Committee in 2014 sparked a worldwide look at American human rights abuses in the Middle East. Initiated in 2007 and chaired by Senator Dianne Feinstein, the committee’s investigation was sourced primarily from internal CIA documents and was covered widely by major news organizations.

Among the key revelations were the use of waterboarding, rectal feeding, and sleep deprivation, as well as the agency’s deliberate misleading of Congress and the White House about the use of those and other torture techniques. The full report has yet to be released to the public, having faced resistance and even attacks from Republican politicians and CIA leadership, but the CIA programs that enabled the behavior were ended by an executive order from President Obama in 2009.

NurPhoto // Getty Images

DNC email leaks (2016)

The last day of the Democratic National Convention in 2016.

Platformed most broadly on WikiLeaks, the trove of emails from Democratic National Committee staffers that indicated the party’s bias towards the nomination of Hillary Clinton over her rival Bernie Sanders was later revealed to have been provided by Russian hackers. The effort, undertaken by a Russian federal agency named the GRU, was a deliberate attempt to influence the outcome of the presidential election and led to DNC chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz resigning just days before the Democratic Party convention. The impact of the leak on the 2016 election is still a matter of debate, but at the very least, it provided fodder for Donald Trump to paint Clinton and the Democratic Party as corrupt.

AFP // Getty Images

Panama Papers (2016)

A sign outside Mossack Fonseca’s building in Panama City.

Containing 11.5 million files of confidential information from the fourth-largest offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca, the leak of the Panama Papers turned the attention of the world to the secret dealings of the ultra-wealthy and the extent to which global institutions could manipulate financial systems to evade taxes and hide their wealth.

Provided to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2015 by a still anonymous source, the papers were then secretly provided to the U.S.-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The ICIJ—which received a Pulitzer Prize for its work on the papers— put together a team of over 300 journalists to research the files, keeping the effort secret until an agreed-upon release date in 2016.

A month later, the anonymous leaker released a 1,800-word statement that defined their motives as rooted in exposing corruption and crime. It also alleged that the state of international watchdog institutions had degraded and that many newspaper giants had declined to review the files. The fallout from the Panama Papers was widespread, leading to the formation of multiple international investigative committees—and the resignation of a number of heads of state, including the Icelandic prime minister.

Matt Cardy // Getty Images

Paradise Papers (2017)

The offices of Bermuda-based law firm Appleby.

On the backs of the Panama Papers, the Paradise Papers contained 13.4 million documents leaked from the Bermuda-based law firm Appleby that detailed an even farther-flung array of offshore investments made by global politicians, companies, and their associates. Similarly, these documents were leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung, which then provided them to the ICIJ. The latter organization has worked with over 30 media partners, including The New York Times and The Guardian, to investigate the information contained within.

Among the revelations were ties between a number of President Trump’s advisors to Russian wealth, detailed information on Apple and Nike’s tax evasion practices, and the exposure of $10 million of the Queen of England’s wealth held in offshore accounts.

Chip Somodevilla // Getty Images

Cambridge Analytica (2018)

Christopher Wylie testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee in the Dirksen Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill.

Whistleblower Christopher Wylie, a former research director at Cambridge Analytica, provided The New York Times, The Observer of London, and The Guardian with a cache of documents showing that the personal data of over 50 million Facebook users had been collected and used for political advertising by Cambridge Analytica. The firm used Facebook’s data to target conspiratorially minded individuals and organizations and spread political disinformation in an effort to support the 2016 political campaign of Donald Trump.

It was later uncovered that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg misled Congress as to when he knew that Cambridge Analytica was a security threat to his platform’s users. More recently, Meta (the parent company of Facebook) paid $725 million to settle a class action lawsuit from the privacy breach in December 2022, despite accepting no wrongdoing.

Robson90 // Shutterstock

FinCEN files (2020)

A sign for JP Morgan on its office building in Dublin, Ireland.

Provided once again to the ICIJ, which then partnered with BuzzFeed News, the FinCEN Files contained over 2,500 documents, which were primarily suspicious activity reports from a wide spread of international banks. SARs are provided to government authorities and regulators by banks outlining activities the banks consider concerning. The FinCEN files contained evidence that HSBC, JPMorgan, Barclays, and other institutions were aware of and had allowed financial activity on accounts that amounted to money laundering—accounts that totaled $2 trillion.

The leak was later revealed to have come from Natalie Edwards, a senior adviser at the Treasury Department who worked at the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, an action for which she was sentenced to six months in prison and three years of supervised release. Though widely hailed as a whistleblower who took action on ethical grounds, Edwards’ actions have been criticized by some as eroding a necessary pipeline of information. Already, banking institutions have altered the way in which they provide information to government agencies as a result of the leak.

BalkansCat // Shutterstock

SolarWinds hack (2021)

SolarWinds logo in front of their office for Brno, Czechia.

One of the largest hacking efforts in recent years, the SolarWinds breach centered around Texas-based SolarWinds, an IT management and software company, which had a large-scale data breach that was undetected by the firm for months. Suspected to have been perpetrated by operatives from Russia, the hack opened SolarWinds clients—such as cybersecurity firm FireEye, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Treasury Department—up to information theft. Given the long duration between when the attack occurred and its detection, U.S. institutions are still reconstructing their digital security and are taking it as a given that breaches currently exist, rather than working to prevent them.

Konstantin Savusia // Shutterstock

Jack Teixeira leak (2023)

A person using Discord on their laptop.

Massachusetts Air National Guardsman Jack Teixeira shared a number of highly classified documents on the social media site Discord. In large part motivated by a pro-gun, pro-military, anti-government outlook, Teixeira also has a history of racist and bigoted remarks and beliefs. Anonymously interviewed acquaintances and schoolmates of Teixeira have described him as an occasionally frightening presence, and one recounted an instance where he’d worn an AK-47 T-shirt to school the day after a mass shooting. The documents Teixeira put online contained a wide range of information, notably detailing military information on the Ukrainian war effort.

In the wake of Teixeira’s April 2023 arrest, new information has come to light that Teixeira’s superiors in the Massachusetts Air National Guard had expressed concern over his handling of classified information on more than one occasion. While the impact of this leak is still playing out in real-time, the exposed documents have revealed U.S. spying efforts on international leaders, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, to whom the U.S. government has made a great show of support in his country’s resistance against Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

On May 19, a judge denied bail for Teixeira, reasoning that he was a flight risk and that foreign powers might have an interest in aiding his avoidance of the U.S. criminal justice system, as was the case with Edward Snowden.

Data reporting by Sam Larson. Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Tim Bruns. Photo selection by Abigail Renaud.