Here’s who’s really in charge of protecting the public

The White House has rolled out a plan to reopen the country, but some state officials say they’re ignoring the directives, while others rush to reopen before health officials — and even the administration’s three-phase plan — say it’s wise.

Then there are city, county and other local leaders who wield their own authority over parts of the pandemic response, from lockdown enforcement and remote schooling to contact tracing and public transit — sometimes at odds with the marching orders of those above them.

It’s clear America’s governments aren’t singing in the same choir.

As states and cities reopen with uneven parameters, the country risks seeing a repeat of episodes it saw earlier in the pandemic.

In February, New Orleans went ahead with Mardi Gras and Miami Gardens, Florida, hosted the Super Bowl, only to say later the events helped spread the virus. New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell is among many local politicians who criticized the federal government’s guidance in the early days of the pandemic.

The blame game is still being played by officials at all levels of government, but when it comes to protecting residents, who really is in charge?

“It’s the federal government whose hands are tied,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “Local governments have that capacity. They have the best idea of what’s going on in a community. … They’re on the ground.”

A World Health Organization epidemiologist concurs, saying Wednesday that integral to reopening is knowing where the infections are, how far they’ve transmitted and whether they’re under control.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all, and what countries need to do — and what decision-makers need to do — is to evaluate the situation in their countries at the lowest administrative level as they can to determine what can be lifted where and when,” WHO’s Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove said.

Locals are hamstrung in certain respects. They can’t shut down an airport or develop their own test kits without federal approval, for instance.

Also complicating matters for local governments is that “some states give more authority to cities and counties than others,” said Elizabeth Kellar, public policy director for the International City/County Management Association.

“There’s sometimes tension between the governor’s preference and the local government’s situation on the ground,” she said.

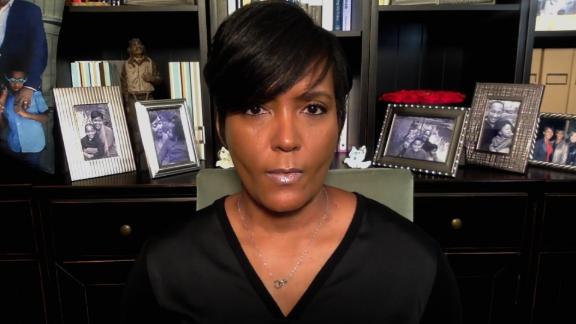

Look no further than Atlanta, where Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms is “at a loss as to what the governor is basing this decision on” and is exploring whether she can legally institute rules for her city that conflict with Gov. Brian Kemp’s order to reopen parts of the state’s economy, she told CNN.

So, when the different levels of government are operating from different, or conflicting, playbooks, what is a city or county government to do? What can residents demand?

Quite a lot, experts say, and that may be important as some states reopen, or if Covid-19 resurges, or in the event of another novel outbreak. Here’s what they advise:

Shut down events where distancing is unlikely

Cantrell has a point when she says federal guidance didn’t point to a need to shut down Mardi Gras. On Fat Tuesday, February 25, President Donald Trump said coronavirus was “very well under control in our country.” The next day, he predicted cases would drop to zero within days.

About a week later, as warnings about the spread of Covid-19 grew more dire, Miami asked the Ultra Music Festival to postpone the electronic dance music party, which it did, and Austin, Texas, put the kibosh on South by Southwest.

Certain gatherings are more conducive to spreading a respiratory virus, and Adalja believes Miami and Austin made the right calls, he said.

“It doesn’t take a lot to understand mass gatherings like Mardi Gras are a focal point for spread,” he said.

Trace and track

This is most important at the outset of an outbreak. Optimally, a testing dragnet would be launched, but when testing faces federal approval and supply chain hurdles, delaying implementation as it did in the United States, knowledge is key, Kellar said.

Local health workers should catalog every person who has Covid-19 and everyone they’ve been in contact with, as well as identify every place an infected person visited.

The latter is especially important because those locations “become areas where when symptoms develop, they know to self-quarantine and get tested,” Kellar said.

Signs should be placed on the doors of those locations, explaining the date and time the patient tested positive, she said.

Educate

If there is one facet of pandemic response where locals face no limitations, it’s educating the public.

Beach Cities Health District, which serves the California cities of Hermosa Beach, Manhattan Beach and Redondo Beach, counts preventative and community health among its primary missions. So when coronavirus hit its radar in January, it began asking residents to exercise caution.

“We wanted to get the word out early. That’s the business we’re in,” district CEO Tom Bakaly said.

Within weeks, it began a dialogue with city, education and business leaders and started issuing advice on how residents could protect themselves.

It isn’t just about washing hands and social distancing, either. The district’s website also includes information on which restaurants offered takeout, stretches to keep the back limber after working at a dining table all day and other ways to improve happiness during the self-isolated life. It also links residents with experts in regular online chats, which served to both educate and connect.

“Worry, stress and feeling disconnected is something we know our community is experiencing, which is why we wanted to tailor or information around that,” Bakaly said.

Jump on the myths

Just as important as disseminating good information is snuffing out bad information and scams, Kellar said.

In addition to informing the public of the latest news on prevention, treatments and vaccines, it’s important to explain: No, those theories you read on Facebook about garlic or booze preventing Covid-19 have no merit. And that robocall you received trying to sell you low-cost Covid-19 insurance? Hang up.

Keeping everybody safe is the practical and common sense mission, she said, but “there’s a lot of noise, I think, that can get in the way of using that common sense,” she said.

Thomaston, Maine, and other jurisdictions across the country experienced some of that noise when residents received texts saying someone they knew had contracted Covid-19 and urged them to get tested.

“DO NOT click the link!” the Thomaston Police Department warned residents, explaining the text was a scam aimed at opening “a gateway for bad actors to find their way into your world.”

Combating the myths can be a little more problematic when leaders are providing different guidance to their constituents.

“We certainly have not spoken with one voice as a nation, and that’s a challenge,” Kellar said.

Coordinate

Cities and counties, especially those where residents cross local borders for work, shopping or recreation, should form regional groups to fine tune their response and recovery. Local demographics and geography are crucial factors in determining how to combat a virus.

It’s also important to consult with state and federal partners, but as Covid-19 has shown, that’s not always possible for local leaders.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declined multiple requests for an interview about how the agency teams with and advises local governments during a pandemic, but its gateway for public health professionals explains how CDC provides data, tool kits, communication tips, case studies from similar jurisdictions and “an informal sounding board” to discuss issues.

Maximize the message’s reach

Local newspapers are useful in spreading information, and local broadcasts are “terribly important,” Kellar said, while social media “is a curse and a blessing.”

Yet just like determining which businesses are essential, one size does not fit all cities, she said.

Are all the languages spoken in a community covered? Are pockets of poverty better reached by public access channels or by local network affiliates that broadcast over the air? Can shelters or community groups help spread the word to the homeless?

Beach Cities Health District did something that’s almost unheard of in 2020: Staffers picked up the phones. Aware it might have issues reaching its older residents, the district — which converted its entire staff to coronavirus-related tasks last month — expanded its call center and touched base with seniors to check on their health and provide them the district’s hotline number.

“It was important to us to just check in with everybody,” Bakaly said. “At a time when we’re asking people to physically distance, we want to make sure they stay connected.”

Protect the most at-risk

Though information showed coronavirus was hitting China’s elderly and smokers the hardest, it seemed less discriminate when it hit American shores, where different health factors are at play. It’s important to know which health factors most affect your community, experts says.

Age is one important factor. Local leaders can protect children by shutting down schools and moving to remote learning. In some cities, leaders have shut down playgrounds or removed basketball hoops in public parks. Protecting the elderly may mean curbing visitation at retirement homes, or asking grocery stores to designate special times for them to shop.

As for the impoverished, leaders should realize the problems inaccessible health care pose — not just during the pandemic, but historically, Kellar said. If a lack of money or insurance prevents someone from going to the doctor, she or he might not even know they have a preexisting condition that could make Covid-19 deadlier, she said.

Bolster supplies

In South Dakota, local governments in rural pockets of the state lack resources and rely heavily on state government. The state’s health systems have been good at spreading important information, but information is but one part of an effective response, said Dr. Robert Summerer, president of the South Dakota State Medical Association.

“As we prepare for a higher volume of patients, we want to make sure we have the appropriate supplies,” he said, adding that having critical care staffing in place is also important.

As the state-v.-state scramble for personal protection equipment and ventilators has shown, a state should have equipment in hand before it needs it, Summerer said, raising questions of storage — and of waste, if the supplies come with an expiration date. There needs to be a plan in place beforehand, he said.

Make telemedicine easy

Also important for those in far-flung locales is access to doctors, a problem only exacerbated during a pandemic when medical professionals might find themselves overwhelmed.

Telemedicine can help, though there are limitations to examining patients via laptops or phones.

“Telemedicine is exploding,” Summerer said. “That’s an area that we’re really going to see grow during the epidemic.”

State and federal legislation can help, he said, as there are concerns about ensuring doctors and staff are paid properly and patients’ privacy is protected, as well as licensing and record-keeping requirements.

Put the right people in charge

This one seems simple, but politics tends to muddy even the most facile of notions.

Just like an emergency manager would be handed the reins during a hurricane, someone with expertise in public health or epidemiology needs to be in charge during a pandemic — and leaders should be looking at success stories on the West Coast and abroad to determine what works and what didn’t, Kellar said.

Some examples might be South Korea’s broad testing initiative that experts say hastened the flattening of the curve in the country, and California’s early stay-at-home order or its rapid procurement of medical equipment, which is said to have saved lives.

“That health officer needs to be in charge,” Kellar said.

Local governments enjoy more public trust than do state or federal governments, she said, so they need to be careful not to betray it. Information should be straightforward, easy to digest and never sugarcoated. Don’t try to scare people, either, she said. You don’t want residents to tune out.

“The places that have done better had residents listening, and doing what needs to be done,” she said.

Set a good example

Leaders lead not just with words but with actions, whether it’s coughing into their elbows or social distancing during briefings.

Kellar pointed to Norwood, Massachusetts, where town manager Tony Mazzucco and 10 other officials self-quarantined in their homes after attending an event where someone had Covid-19.

Mazzucco later shared his own positive test and regularly updated the media on his condition and quarantine, advice from local and state health officials and Norwood’s plan of action, which included disinfecting town hall.

In Montgomery County, Maryland, County Executive Marc Elrich has repeatedly provided positive examples for his community, including posting a YouTube tutorial of himself “clumsily making his own mask” from an old purple T-shirt, Kellar said.

“It helps when local leaders also model what needs to be done,” she said. “They wear their masks when they’re out.”