Here’s why the US is behind in coronavirus testing

As the US has lagged behind other advanced nations in testing for the coronavirus, former government officials and public health experts point to a series of policy and procedural decisions that they say hindered the nation’s response to the pandemic.

South Korea had run more than 300,000 tests as of Friday, and while there is no official count of tests done in the United States, Dr. Deborah Birx, part of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, implied about 170,000 people have been tested so far. The US population is more than six times that of South Korea.

For weeks public and private labs have raced to boost their testing capacity, but people across the country, even some with underlying health conditions, have told CNN this week that they have not been able to get tested.

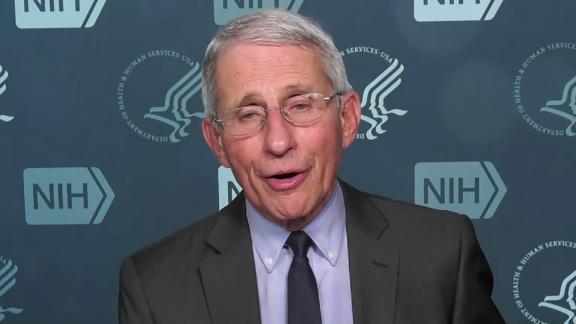

Asked Friday whether the US can currently meet demand for tests, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said, “We are not there yet.”

The CDC’s first test didn’t work

In January, shortly after Chinese authorities identified a novel coronavirus as the cause of cases of pneumonia in Wuhan, the World Health Organization published a protocol with instructions for any country to manufacture tests for the virus.

Rather than using that protocol, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed its own test. A WHO spokesperson said this week that the WHO didn’t offer tests to the CDC because the US agency typically has the capacity to manufacture them itself.

On February 5, the CDC said it would begin shipping test kits to health labs throughout the country, but in subsequent days public labs found a defect. When public labs first receive any test kit, they first verify that it works.

“It gave them an inconclusive result, so the test was not valid,” said Scott Becker, the CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

A CDC official said on February 12 a part of the test needed to be remanufactured.

It was weeks before new CDC tests were sent out

Michael Mina, an assistant professor of epidemiology and immunology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said that in addition to originally sending out flawed tests, the CDC added to the confusion by providing limited information to labs in the weeks that followed.

“There was a period of time after the tests were recalled where there was near silence. It was about two weeks. And this caused confusion among labs about what, if anything, hospital laboratories could do,” Mina said. “While we are on the correct trajectory now, we are unfortunately weeks behind where we should be as a country.”

Jeremy Konyndyk, an expert on global pandemic preparedness, agreed that significant delays resulted from the CDC sticking with only its test.

“The whole diagnostic capability of the United States against this disease was hung up on one test being produced at CDC,” said Konyndyk, formerly a director with the US Agency for International Development and now with the Center for Global Development. “And when that test failed, all of the testing outside of it, outside of what CDC itself could do and its own lab, was held up. That kept us from having visibility on domestic transmission of the virus for weeks and weeks and weeks.”

Fauci has said the CDC has for years followed a process of developing its own test and providing that to public health departments throughout the country.

Though when asked during CNN’s coronavirus town hall last week whether the US should have used the WHO tests, Fauci said, “If you look back and Monday morning quarterback it would have been nice to have had a backup.”

Red tape kept labs from using their own tests

The US Food and Drug Administration also received criticism in February as the tally of cases climbed globally.

More than 100 virologists and other specialists wrote a letter to Congress on February 28 that said many of their labs had already validated tests for coronavirus that they could not run due to the FDA’s protocol for approving tests during outbreaks — known as emergency-use authorization.

The letter protested the FDA’s regulatory process as “significantly more stringent than that required for every other virus we test for.” The letter said the result was “undue pressure on the CDC and state public health labs to rapidly scale manufacturing and clinical testing.”

On February 29, FDA issued new guidance that allowed certain US labs to test for coronavirus using diagnostics the labs developed and validated, before the agency reviewed them.

Dr. Alex Greninger, an assistant professor at the University of Washington’s Department of Laboratory Medicine and one of the letter’s signatories, said the emergency-use authorization process in place in February would have taken weeks for clinical labs and others to clear.

“You have to give credit to the FDA, they have changed their policies significantly,” said Greninger, who added that the transmissibility of the coronavirus seemed to defy regulations previously established by the government. “How do you regulate something you’ve never seen before?”

In a statement, the FDA said laboratories have had the ability to develop their own tests from day one and that the FDA’s independent check is important to ensure the accuracy and reliability of tests.

On why it issued new guidance, the FDA said that “under the current circumstances, which are unlike any prior emergency we have seen, we think the benefit of access to certain tests outweigh the risks associated with launching tests prior to FDA review.”

Severe shortages of swabs and other supplies

Even though commercial labs ramped up the testing, medical workers at several state health departments, hospitals and labs told CNN that they’re running low on materials needed to conduct the tests, like swabs, reagents, which are the testing chemicals, and pipettes, which are tools for transporting liquids. The shortage forced Minnesota and Ohio to limit testing to the most vulnerable patients.

“I’m really concerned that we are not going to have the capabilities to test those who really need and should get a test,” said Becker of the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

The FDA said earlier this week it is well aware of the shortages and is providing information “on alternative sources of reagents, extraction kits, swabs and more.”

The Trump administration restructured the pandemic unit

Some former officials from President Barack Obama’s administration have argued the Trump White House undercut its ability to respond to the coronavirus by restructuring in 2018 a team that dealt with pandemics, known as the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense.

“Would we have gotten more ahead of this if the office had still been intact? I think absolutely,” said Beth Cameron, the former senior director for that NSC team, who is now with the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

John Bolton, then Trump’s national security adviser, tweeted Saturday that such claims “are false. Global health remained a top NSC priority.”

Last week, Trump declined to take responsibility for the NSC changes when a reporter asked him about the issue. “I didn’t do it,” he said.

The White House has said the NSC’s global health directorate was absorbed into another directorate with similar responsibilities but different titles.

Others have defended the speed with which the government and industry have moved to increase testing capacity.

Test supplier Roche Diagnostics Corp., which says it is now distributing 400,000 tests per week to labs in the United States, said in a statement that test development usually takes about 18 months in addition to the FDA’s review time. A company spokesperson said Roche developed a coronavirus test and was issued an emergency-use authorization in about six weeks.

Birx, the White House coronavirus task force coordinator, said the administration has in recent weeks cut red tape and bureaucracy to expand test capacity while upholding a quality of tests superior to those used in some other countries.

“Over the next few months, you will begin to see that other tests that were utilized around the world were not of the same quality, resulting in false positives and potentially false negatives,” Birx said Tuesday.

“It doesn’t help to put out a test where 50% or 47% are false positives,” she added.

The New York Times reported Tuesday that Birx later clarified that she was referring to a study of an early coronavirus test used in China. That study found that nearly half of asymptomatic people in China could test positive for Covid-19 without being actually infected.

Asked earlier this week how he would rate his administration’s response to the virus on a scale of 1 to 10, Trump said, “I’d rate it a 10.”

“We’re doing something that’s never been done in this country. And I think that we are doing very well,” he said.