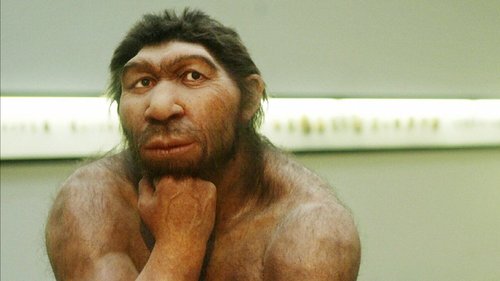

Inbreeding may have helped cause Neanderthals to go extinct, study says

Neanderthals went extinct around 40,000 years ago — about the same time that modern humans migrated out of Africa. This has led researchers to believe that modern humans won the competition for resources, leading to the demise of Neanderthals.

Other theories around the environmental pressure of climate change or even epidemics maintain those reasons could have helped Neanderthals to go extinct.

But a new study proposes that modern humans had nothing to do with it. Instead, the researchers suggest that inbreeding, small populations and fluctuations in birth, death and sex ratio would have been enough to lead the Neanderthals to their permanent end. The study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS.

Previous research suggested that Neanderthals had small populations before modern humans made their appearance. Neanderthals were also spread out in isolated, local areas.

The researchers for this study created population models, based on data from hunter-gatherer groups, with a range of population sizes as small as 50 to a maximum of 5,000.

They simulated the population change in response to changes in birth and death rates, inbreeding and a factor known as Allee effects. Allee effects are when small population size has a negative impact on the reproductive fitness of individuals.

Inbreeding, a practice of mating between relatives, was common among Neanderthals according to previous research. Inbreeding also leads to a reduction of reproductive fitness.

Neanderthals had 40% lower reproductive fitness than modern humans, according to previous research cited in the new study.

The simulations took place on a 10,000-year timescale. The researchers found that it was unlikely that inbreeding could be solely responsible for extinction because it only occurred in the model with the smallest population.

But Allee effects, like 25% or less females giving birth in one year, could have caused extinction in populations with 1,000 Neanderthals. Combined with inbreeding and fluctuations in birth and death rates, extinction would have been likely on their timescale over 10,000 years.

The researchers allowed that if modern humans had any effect on Neanderthal extinction, it’s possible that the Neanderthal populations may have shifted — which could lead to inbreeding, a low birth rate and other factors accounted for in the study.

“Did Neanderthals disappear because of us? No, this study suggests,” the authors wrote. “The species’ demise might have been due merely to a stroke of bad, demographic luck.”