MLB’s Ian Desmond, in a powerful post about racism and social injustice, opts out of the 2020 season

DENVER, Colorado — Major League Baseball player Ian Desmond is opting out of the truncated 2020 season. Coronavirus concerns factored into his decision, but so did the national reckoning with racism — something Desmond says needs to happen within the league, too.

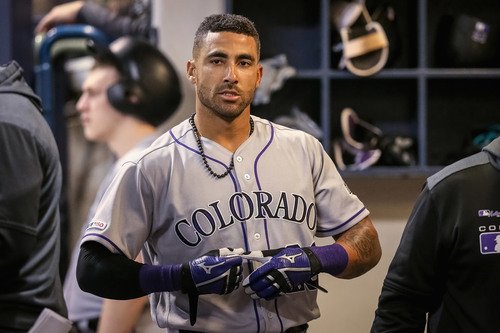

The Colorado Rockies outfielder, in a lengthy and emotional Instagram post, detailed how he made his decision and how racism impacted his life within the sport and outside of it as a biracial Black man.

Desmond, an 11-year MLB veteran, has played the past three seasons with the Rockies after signing a five-year, $70 million contract.

Desmond said he’s been inspired to speak out about his experiences with racism since the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. And in his Instagram essay, he outlined just how much of his life has been touched by racism, from his grade school hosting a meeting for White families to tell them Desmond and his sister would be enrolling, to his high school team chanting “White power” ahead of games and now, in his career in the MLB.

“I’m immensely grateful for my career, and for all people who influenced it,” he said. “But when I reflect on it, I find myself seeing those same boxes. The golden rules of baseball — don’t have fun, don’t pimp home runs, don’t play with character. Those are white rules. Don’t do anything fancy. Take it down a notch. Keep it all in the box.”

He’s overheard racist, homophobic and sexist jokes in clubhouses. There are very few Black managers, he said, and a low percentage of players are Black. It’s a problem in the league that Desmond said he’s seen no concerted effort to fix.

By opting out, Desmond forgoes his salary for the season because he’s not considered a “high-risk” player, MLB.com’s Thomas Harding reported.

“We’re fully supportive of Ian and of his family and of the decision they’ve made,” Rockies general manager Jeff Bridich said Tuesday. “It’s the right decision for them and for him. … What he put out there was quite heartfelt yesterday.”

Desmond will still spend the season on a baseball field — just a Little League diamond in Sarasota, Florida, where he grew up. He’ll work to get the town’s youth baseball league “back on track,” he said.

“With a pregnant wife and four young children who have lots of questions about what’s going on in the world, home is where I need to be right now,” he said. “Home for my wife, Chelsey. Home to help. Home to guide. Home to answer my older three boys’ questions about Coronavirus and Civil Rights and life. Home to be their Dad.”

Other players opt out of MLB season

Major League Baseball’s rescheduled season will resume on July 23 or 24, league commissioner Rob Manfred said last week. The 2020 regular season never started because of the pandemic, and spring training was cut short.

Now, players are expected to report for training this week, on July 1.

But a few players have opted out of the season, citing health concerns.

Washington Nationals infielder Ryan Zimmerman and pitcher Joe Ross will not play, the team confirmed on Monday. Neither will Arizona Diamondbacks right-handed pitcher Mike Leake, according to a statement from his agent. Zimmerman and Leake both said family factored into their decisions.

Read Desmond’s statement in full:

“A few weeks ago, I told the social media world a little bit about me that I never talk about. I started it by saying why that was: I don’t like sadness and anger. I’d found an even keel allowed me to move through my days with more ease than emotion did. So, I kept it inside. But that comes at an internal cost, and I could no longer keep a lid on what I was feeling. The image of officer Derek Chauvin’s knee on the neck of George Floyd, the gruesome murder of a Black man in the street at the hands of a police officer, broke my coping mechanism. Suppressing my emotions became impossible.

In the days since I began sharing my thoughts and experiences as a biracial man in America, I’ve received many requests to elaborate. But, it’s hard to know where to begin. And, in truth, there’s a lot on my mind. Here’s some of it.

Recently, I took a drive to the Little League fields I was basically raised on here in Sarasota.

They’re not in great shape. They look run down. Neglected. When I saw a Cal Ripken Little League schedule tacked on a bulletin board, I walked over to check it out, and it was from 2015. The only thing shiny and new, to my eye, was a USSSA banner. Travel ball. Showcases. So, not so much baseball for all anymore… as much as baseball for all who can afford it.

I walked around those fields, deserted at the time, and my mind raced. I stopped at a memorial for a man named Dick Lee; Coast Federal Head Coach and manager, Sarasota Little League, 1973-1985. There was a quote from him on the plaque:

‘Many men have cherished some of their greatest moments in life while stopping and taking time to reflect back on the young men they have helped develop, from childhood into manhood, with the ability to carry on in life. In no other activity has man been able to see this growth better than he has in the heart and character of this nation.

‘To see our youth grow and develop in the knowledge and skills to play baseball is a reward that only one who has been involved with would know. Baseball not only develops the physical skills of our youth, but develops a person with a knowledge of fair play while always stressing a desire to win.

‘That great moment comes when you look at the final product and realize the job done. There’s nothing more satisfying when watching these young men than hearing that familiar voice call out “Hi, coach!” transcending that special spirit of pride.’

I know it sounds simple to say, as a Major League Baseball player, that these fields were important in shaping my life. But I don’t mean my career.

I read Dick Lee’s words, and I stood there and I thought about when I was 10, and my stepfather dropped me off for a baseball tryout. He never came back to get me. Later, as I sobbed alone at the top of the bleachers, a kind stranger offered me a chance to make a phone call to alert my mom.

I thought about the moment, not too long after that, when my coach, John Howard, seeing I was upset about an out or something, wrapped me in an embrace so strong that I can still remember how his arms felt around me. How it felt to be hugged like that; embraced by a man who cared about the way I was feeling.

Then, another memory hit me: my high school teammates chanting ‘White Power!’ before games. We would say the Lord’s prayer and put our hands in the middle so all the white kids could yell it. Two Black kids on the whole team sitting in a stunned silence the white players didn’t seem to notice. I started to walk the fields a bit, and that’s when I thought of Antwuan.

These fields are where I learned a game that I’ve played 1,478 times at the Major League level. It started when I was 10, 11, 12 years old — exactly how old Antwuan was (12) when I met him at the Nationals Youth Baseball Academy in D.C.

He couldn’t read. He could barely say his ABCs. One morning, when his mom was shuffling Antwuan and his siblings off to their aunt’s house at 4 a.m. so she could get to work, they opened their door to a man stabbed to death on the ground. So, no sleep, traumatized by murder literally outside their door, eating who knows what for lunch, they head off to school. And they’re expected to perform in a classroom?

Meanwhile, my kids fly all over the country watching their dad play. They attend private schools, and get extra curriculum from learning centers. They have safe places to learn, grow, develop. But… the only thing dividing us from Antwuan is money.

It just doesn’t make any sense. Why isn’t society’s No. 1 priority giving all kids the best education possible? If we seriously want to see change, isn’t education where it all starts? Give all kids a safe place to go for eight hours a day. Where their teachers or coaches are happy to see them. Where they feel supported and loved.

I went back to those Little League fields because I wanted to figure out why they were thriving the way I remembered. What I came away with was more confusion.

I had the most heartbreak and the most fulfillment right there on those fields — in the same exact place. I felt the hurt of racism, the loneliness of abandonment, and so many other emotions. But I also felt the triumph of success. The love of others. The support of a group of men pulling for each other and picking one another up as a team.

I got to experience that because it was a place where baseball could be played by any kid who wanted. It was there, it was affordable, and it was staffed by people who cared.

But if we don’t have these parks, academies, teachers, coaches, religious institutions — if we don’t have communities investing in people’s lives — what happens to the kids who are just heartbroken and never get that moment of fulfillment?

If what Dick Lee knew to be true remains so — that baseball is about passing on what we’ve learned to those who come after us in hopes of bettering the future for others — then it seems to me that America’s pastime is failing to do what it could, just like the country it entertains.

Think about it: right now in baseball we’ve got a labor war. We’ve got rampant individualism on the field. In clubhouses we’ve got racist, sexist, homophobic jokes or flat-out problems. We’ve got cheating. We’ve got a minority issue from the top down. One African American GM. Two African American managers. Less than 8% Black players. No Black majority team owners.

Perhaps most disheartening of all is a puzzling lack of focus on understanding how to change those numbers. A lack of focus on making baseball accessible and possible for all kids, not just those who are privileged enough to afford it.

If baseball is America’s pastime, maybe it’s never been a more fitting one than now.

Antwuan was 12 years old when he started going to the Nationals Youth Baseball Academy — because that’s when it started existing in his universe as a resource. We got him a tutor, he got into other programs, and he learned to read. He was on the right track.

He died when he was 18, shot 31 times in D.C. A 16-year-old kid was just arrested for his murder.

It’s almost safe to say that the best years of his life came from that Academy… and yet the staff running it have to beg people to invest money and time.

How can that be? Why isn’t there an academy like that in every single community? Why does Major League Baseball have to have a specific youth baseball affiliate with RBI? Why can’t we support teaching the game to all kids — but especially those in underprivileged communities? Why aren’t accessible, affordable youth sports viewed as an essential opportunity to affect kids’ development, as opposed to money-making propositions and recruiting chances? It’s hard to wrap your head around it.

I won’t tell you that I look around at the world today — baseball or otherwise — and feel like I have the answers. I don’t. I’m not a perfect person. I kept my emotions inside for so long because it seemed easier to numb myself than to embrace the why behind my feelings.

Doesn’t it seem easier to just block it out when you walk down the street and see women clutch their purse at the sight of you? To push it behind you when you find out your grade school had to hold a meeting for all the students to let them know you and your sister — two Black kids — were about to enroll? To slough it off when someone makes a racist joke, or suggests you must be an athlete because how else could you have such a nice house? It forced me into a box.

And, in a lot of ways, I feel like everything in my life has been about boxes.

I remember, as a biracial kid, I dreaded filling out paperwork. I feared those boxes: white, Black, other. The biracial seat is a completely unique experience, and there are so many times you feel like you belong everywhere and nowhere at once. I knew I wasn’t walking around with the privilege of having white skin, but being raised by a white mother (an incredible mother), I never fully felt immersed in Black culture.

I almost always checked Black. Because I felt the prejudices. That’s what being Black meant to me: do you feel the hurt? Do you experience racism? Do you feel like you’re at a slight disadvantage?

Even in baseball. I’m immensely grateful for my career, and for all people who influenced it. But when I reflect on it, I find myself seeing those same boxes. The golden rules of baseball — don’t have fun, don’t pimp home runs, don’t play with character. Those are white rules. Don’t do anything fancy. Take it down a notch. Keep it all in the box.

It’s no coincidence that some of my best years came when I played under Davey Johnson, whose No. 1 line to me was: ‘Desi, go out there and express yourself.’ If, in other years, I’d just allowed myself to be who I was — to play free and the way I was born to play, would I have been better?

If we didn’t force Black Americans into white America’s box, think of how much we could thrive.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made this baseball season one that is a risk I am not comfortable taking. But that doesn’t mean I’m leaving baseball behind for the year. I’ll be right here, at my old Little League, and I’m working with everyone involved to make sure we get Sarasota Youth Baseball back on track. It’s what I can do, in the scheme of so much. So, I am.

With a pregnant wife and four young children who have lots of questions about what’s going on in the world, home is where I need to be right now. Home for my wife, Chelsey. Home to help. Home to guide. Home to answer my older three boys’ questions about Coronavirus and Civil Rights and life. Home to be their Dad.

Ian Desmond”